Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

GERMAN DOCTRINE OF THE STABILIZED FRONT

IL SERIES, NO. 17, I5 AUGUST 1943

GERMAN DOCTRINE OF THE STABILIZED FRONT

PREPARED BY

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE DIVISION

WAR DEPARTMENT WASHINGTON 25, 15 AUGUST 1943

SPECIAL SERIES

No. 17

MID 461

FOREWORD

German policy has consistently emphasized the development of highly mobile armies, and Germany's military successes have been gained in wars of maneuver. During the past 25 years the German High Command has become thoroughly convinced of the soundness of the Schlieffen theories of movement, envelopment, and annihilation, especially since Germany's central location- in Europe gives her the advantage of interior lines of communication—a decided strategic advantage in a war of maneuver. Indoctrined and trained in the Schlieffen theories, German armies were successful in the Franco-Prussian War, in World War I (until they became involved in trench warfare of attrition), and in the Polish, Norwegian, and western European campaigns of World War II.

However, Germany's central position ceases to be an advantage "whenever her enemies can so combine that they engage her in a two-front war. Her transportation, manpower, and other resources are not sufficient to insure a decisive victory on two sides at once. In order to escape this prospect, the German High Command reached the conclusion that at least one side Germany could and must- secure herself with a great fortified system.

A doctrine of permanent fortifications, exhaustive in scope, was formulated under the title "The Stabilized Front" (Die Standige Front). The classic concept of fortifications—isolated fortress cities and a line of fortified works—was abandoned as obsolete. The German High Command developed new principles in the light of modern warfare, weapons, and air power which called for the construction of permanent fortifications in systems of zones, organized in great depth. By "stabilized front" they meant not only the fixed positions which the field armies might be compelled to establish during a campaign, but also the 'deep zones of fortified works which would be constructed in peacetime. (See par. 8)

The primary mission of the fortifications in the west was to serve at the proper time as the springboard for an attack; however, until that time came, they were to protect Germany's western flank while she waged offensive war in the east. Thus the West Wall was conceived as a great barrier against Prance and the Low Countries. But it is essential to realize that the conception of the West Wall, far from committing the German High Command to a passively defensive attitude, gave all the greater scope to the offensive character of its doctrine. The entire German Army, including the units assigned to the West Wall, was indoctrinated with the offensive spirit and thoroughly trained for a war of movement.

The role of fortifications in the German strategy was summarized in the following statement of General von Brauchitsch, then German Commander-in-Chief, in September 1939:

"The erection of the West Wall, the strongest fortification in the world, enabled us to destroy the Polish

Army in the shortest possible time without obliging us to split up the mass of our forces at various fronts, as was the case in 1914. Now that we have no enemy in the rear, we can calmly await the future development of events without encountering the danger of a two-front war."

This study does not propose to judge the soundness of the German concept of fortifications. It may be pointed out, however, that in formulating its doctrine, the German High Command did not foresee that the German West Wall and the great coastal defenses in the occupied countries would not protect vital war industries against massive and destructive attacks from the air. The aim of this study is to provide a digest of German principles of modern fortifications and the available information concerning the various lines of permanent and field fortifications which Germany has constructed within and outside her frontiers.

Part 1 GERMAN PRINCIPLES OF FORTIFICATIONS

Section I. STRATEGIC

The Germans regard economy of force as the fundamental rule to be observed in planning zones of permanent fortifications. Their aim is to achieve an effective defense with a minimum of manpower so that the bulk of the field armies will be left mobile and free for offensive action elsewhere. In other words, a very small portion of the nation's military strength or of its training effort is allocated specifically to the permanent defenses, and even the troops that are assigned to fortifications receive the same tactical training as the troops in the field armies.

A permanently fortified zone, as the Germans conceive it, must serve two purposes: primarily it is to be a base for offensive operations, and secondarily it is designed to protect some vital area or interest of the defender.

The value of such a zone depends upon the length and geographic nature of the national frontiers, the funds available for its construction, and the potential strength of the enemy. According to German doctrine, there is no real military value in a fortified zone which may be strategically outflanked; neither is there any reason for such fortifications when the opposing combination is either much weaker or much stronger than the defender. Likewise the economic cost of a fortification system must not be so great as to deprive the field armies of adequate fluids for training and

equipment, but enough must be expended to make it as strong as necessary. The German doctrine also assumes that the natural progress of technology will produce weapons which will limit the value of any specific defenses to a term of years. Therefore, the Germans construct their fortifications to solve a definite existing strategic problem rather than to forestall the problems of the future.

For the purposes of strategic offense, the Germans place a fortified zone close enough to the border to serve as a basis of military operations against the neighboring nation. For the purposes of, strategic defense, they construct it far enough back from the frontier to deprive an enemy attack of force before it can reach the main defenses. In either case, the fortified zone is generally located far enough inside the border to make it impossible for the enemy to bombard it with heavy batteries emplaced on his own soil. However, in exceptional eases—where, for instance, heavy industries must be protected—the Germans may build a defensive zone immediately adjoining the enemy border.

In a German fortified system the flanks are drawn back as far as possible, unless they can be rested on impregnable natural obstacles or on the frontiers of friendly countries which are capable of maintaining their neutrality.

When a German fortified zone lies along a river bank, the system includes a number of bridges and large bridgeheads, so that the defenders may carry out counterattacks. As always, German defensive doctrine

is posited upon the principle that offensive action is ultimately the best protection.

The fortified zone as conceived by German theorists is designed to permit free lateral movement of troops, and to provide space and means for effective counterattack. For the offensive, the Germans maintain, a zone of man-made fortifications has definite advantages over natural obstacles, such as mountain ranges or rivers, because a zone system permits field armies to debouch for an attack at any desired point or points. Likewise, field forces may retire more easily through a fortified zone.

Isolated fortifications like the fortress city,, even those provided with all-around protection, are considered obsolete by the Germans, who have concluded that the civil population of a fortress city is a burden to the defenders, and, moreover, that such a city is vulnerable to incendiary air bombardment.

Section II. TACTICAL

1. ROLE OF TROOPS

a. Offensive Spirit

German doctrine holds that the infantry must be the deciding factor in combat within fortified zones, as well as in a war of movement. The tenacious resistance of the infantry under even the heaviest fire, and its fighting spirit in making counterattacks, are the measure of .the strength of the defense. The decision is usually achieved on the ground between bunkers by the infantryman in hand-to-hand combat—with his rifle, bayonet, and hand grenade. . No less determined must be the defense of any permanent installation, according to the German doctrine, which states that the main fortified position must be held against all attacks, and that each link in its works must be defended to the last bullet. An effort is made to imbue every German soldier with the will to destroy the attacker. The German soldier is also taught to continue to fight even though the tide of battle flows over and around him.

Permanent fortifications, the German soldier is told, must never be surrendered, even when all weapons are out of action through lack of ammunition or reduction of the position. The reason for this principle is that the perseverance of the garrison, even without active fighting, impedes the enemy's advance and facilitates the counterattack. Herein lies a basic difference between the German view of defensive fighting on permanent fortified fronts and of the defense in war of movement: in the latter the loss of an individual position is not considered critical.

Heavy infantry weapons and the artillery are the backbone of the German defense in a permanent position. During heavy and prolonged bombardment, the permanent installations, with their concrete and armor plate, protect the weapons and their crews, and keep the unengaged troops in fighting trim for the eventual counterattack. In this sense only, the Germans consider fortified zones tactically defensive in character. Individual bunkers may be taken by a determined attacker, but, because of their large number and dispersion, organized resistance by the remaining works can continue until mobile forces are brought up to eject the enemy.

b. Counterattack

The Germans consider it essential to make provision for small local infantry reserves in a fortified position. These reserves are protected by strong overhead cover and can be shifted rapidly by means of underground tunnels to the area where they are required for counterattack. As soon as the attacker has taken possession of any portion of the fortified zone, these reserves are sent into action in order to strike before the enemy can organize his gains. For the counterattack, the Germans claim the defender has the advantage of a coordinated and complete observation and communication system. In addition the defender brings his sheltered reserves into action in fresh condition, without the casualties that are suffered when they pass

through artillery fire, and without the loss of time entailed in bringing reserves up from the rear.

The Germans attempt to provide against the failure of the local reserves to break up an attack by arranging for additional reserves to be brought up from the rear, either by underground tunnels or by camouflaged roads. Every effort is made to give these reserves artillery support and to acquaint them thoroughly with the terrain. Sector reserves and the units of the intermediate zone may begin the counterattack without specific orders. Units with security missions do not take part in the counterattack.

The Germans believe that the most favorable time for a large-scale eountei'attack is the moment when the enemy artillery and antitank weapons are advancing to new positions. Provided the situation permits, the afternoon is considered preferable to morning, because then, after the objective is reached, the regained terrain can be consolidated during the hours of darkness.

As a rule, the troops held in readiness for a general counterattack are employed as a unit. The Germans consider it advantageous to attach them to a division in line for the sake of the uniform conduct of battle. If the situation requires that parts of a division be detached for the support of other units, the Germans subordinate them to the commander of the corresponding battle sector.

Should the enemy succeed in penetrating the main fortified position at several points, the Germans prescribe that the other attacked positions must continue the battle without regard to the situation at the points

of penetration. The enemy penetrations are dealt with by battle installations' in the rear, protective flank installations, and heavy infantry weapons not otherwise employed, which direct their fire against the points of penetration and attempt to destroy the enemy before lie consolidates his gains. The Germans constantly renew barrage fire of all weapons beyond the points of enemy penetration in order to delay the enemy and make it difficult for him to bring up additional troops. Isolated battle installations, for which the enemy is fighting in close combat, are brought under the controlled fire of neighboring light and heavy infantry weapons, and of light artillery. However, the heavy infantry guns are not employed in such a situation in order that crews within the friendly installations will not be endangered.

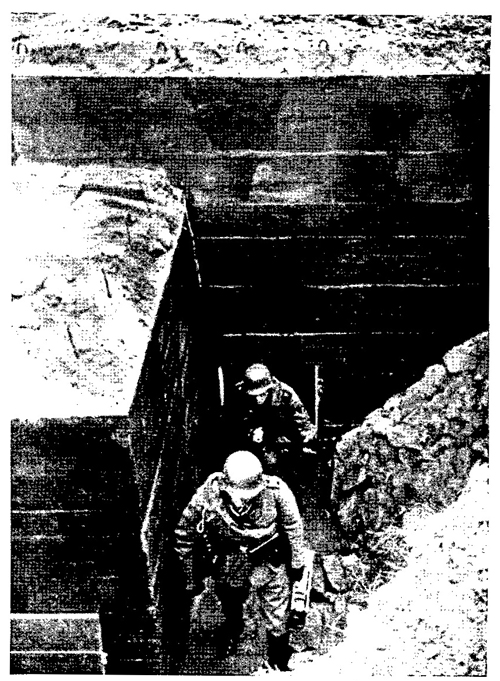

c. Relief

Another essential function of German reserves is regularly to relieve troops employed in a fortified zone in order that their fighting strength may be maintained or restored. Because of the special missions of permanent troops, their relief can be thoroughly prepared, and is carried out without interrupting the Continuity of the defense. The length of relief depends on the condition of the men as well as on the strength of available forces. The relief is effected in such a manner that the relieving units arrive after dark, and in any sector which is subject to ground observation the relieved units move out before daybreak. Advance detachments prepare the relief; guides and orientation detachments direct the relieving units. Complete readiness for defense is maintained, and the usual combat activities are continued at all times during these relieving operations.

2. PERMANENT AND FIELD FORTIFICATIONS

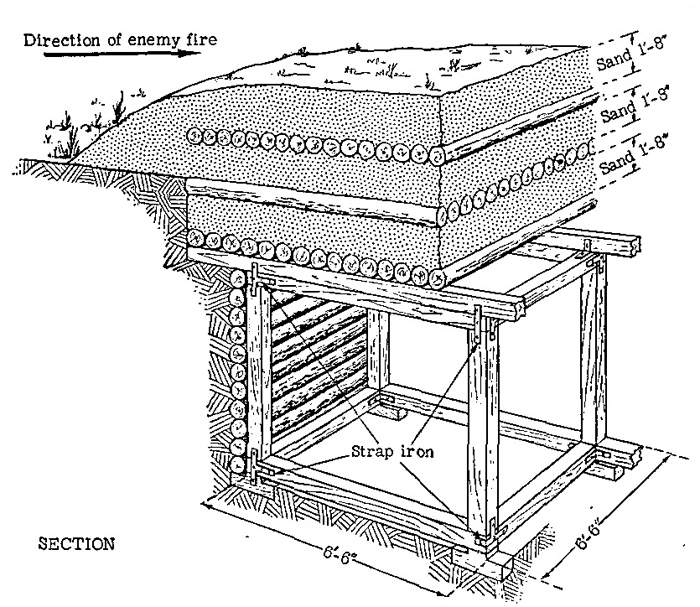

a. Comparison of Permanent and Field Works

The Germans realize that while permanent fortifications conserve manpower, they require a great deal of money and labor prior to hostilities. Field fortifications cost much less in labor and money but require strong forces and great courage for their defense. The Germans also realize that both modern tanks and high-angle heavy artillery weapons are so mobile that the attacker can always bring them within range of any defensive zone. The fire of these weapons, as well as air bombardment, is effective against field fortifications, but it is not so serious against permanent defensive works. The ideal solution of the problem in a modern defensive system, the Germans conclude, is to lay out both permanent and field fortifications so that they complement each other and take full advantage of the terrain.

Another German principle is that the weakest terrain should be provided with the strongest and most numerous permanent defensive works, organized in great depth, but only after the relative defense effectiveness of the terrain and of permanent fortifications has been carefully judged. The defended zone is everywhere made as strong as the available resources permit, and no terrain is left entirely without the protective fire of some permanent defensive works.

b. Characteristics of Individual Works

The Germans have recognized the rule that the defensive strength of a fortification system depends upon the ability of individual works to deliver continuous short-range flanking and supporting fire from automatic weapons, and to afford moral and physical protection, relief, and" unlimited ammunition supply for the defending crews. The works are placed far enough apart so that enemy artillery fire that misses one installation will not hit the others. Also, they are so placed that all the terrain is effectively covered by observation and fire. In the general organization of a position, the Germans endeavor to make it difficult for the enemy to discover the vital centers of resistance so that he may be kept in doubt as to where he should employ his heavy indirect fire.

Widely distributed works are generally joined by connecting trenches to form defensive systems. Fortifications are constructed for all-around defense of platoon or company defense areas; they may be combined into closely organized battalion defense areas or echeloned in width and depth. The strength, size, garrison, armament, and equipment of such works depend upon the mission of the fortifications. They are so located as to permit a system of zone defenses. Fire from such positions, the Germans believe, is especially effective because even under enemy bombardment exact aim and rigid fire control can be maintained. Large isolated permanent fortifications unsupported by the fire of other fortifications are considered obsolete by the Germans.

Because of the relative dispersion of the works and of the thoroughness of the antiaircraft defenses, the Germans consider air bombardment an uneconomical means of destroying a modern fortification system. Therefore, they employ a greater proportion of the defending air forces in general support, as well as in local support of large counterattacks.

Where decisive resistance is to be maintained, the Germans design concrete and steel works strong enough to provide moral and physical protection against the enemy's heaviest indirect fire. Careful study is made of enemy artillery—its power, range and mobility—and special provision is made in those areas which can be reached by long-range guns. The Germans believe that the thickness of concrete covering necessary to withstand effective artillery fire is approximately ten times the maximum caliber of the artillery that may fire on it. When the German High Command has decided that a permanent fortification is required, it specifies that it should be built according to these basic requirements.

Infantry weapons only are generally emplaced in permanent works. Artillery and other supporting arms are placed mainly in open positions, with their normal field protection, in order to retain mobility. At critical points where continuous fire is essential, some artillery may be permanently emplaced.

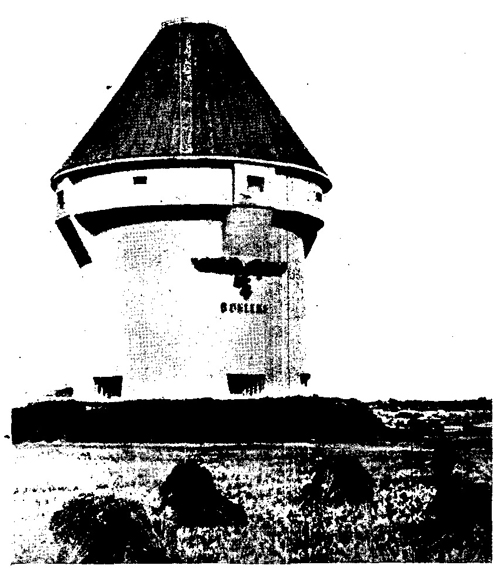

Concrete bunkers are generally used for flanking fire in positions which are protected from direct observation by the enemy. Steel turrets are used on all works which fire frontally and which consequently

are constructed with low silhouettes for good concealment; they are also considered essential for flanking fire in flat terrain.

c. Field Fortifications

German permanent works are supplemented extensively by field fortifications and alternate weapon emplacements whose fire missions include protection of sally ports, communication routes, and defiladed areas. The field fortifications also allow crews to continue the fight when their permanent positions have been neutralized, and provide firing positions for reserves in the counterattack.

According to German doctrine, field fortifications are constructed in time of tension or war to reinforce stabilized fronts. The construction of these works is carried out according to plans prepared in peacetime by construction units or by troop units assigned to the fortifications. Available equipment and tools and, to some extent, building materials prepared in peacetime are used for this purpose. With a conflict imminent or already started, construction embraces the works listed below, the number and scope in each sector being dependent on the strength of fortifications that were completed in peacetime:

(1) Obstacles in the outpost area.

(2) Reinforcement of the obstacles in the advanced

position and in the main battle position.

(3) Open emplacements for light and heavy infantry

weapons in the terrain between permanent installations, and in the depth of the main battle position,

(4) Splinterproof dugouts in the vicinity of the emplacements.

(5) Observation posts, artillery emplacements, and

cover for the crews.

(6) Command posts and dugouts of all kinds.

(7) Trenches of all kinds—shallow and normal communication trenches, fire trenches, approach trenches,

and telephone wire trenches.

(8) Dummy installations and camouflage.

(9) Deep shelters in the rear sector of the main

battle position, and also behind the battle position, if

the terrain is suitable.

(10) Flanking obstacles and rear positions.

The value of field fortifications lies, according to German principles, in their small size, their great number, and their slight camouflage requirements. They compel the enemy to disperse his fire.

Temporary emplacements for heavy infantry weapons and artillery are employed to engage the approaching enemy in the advanced and outpost positions without betraying the location of the permanent installations. Temporary positions may also be used as alternate positions. The construction, as well as the maintenance and repair of field fortifications, is continued by the troops during combat. Dugouts affording more protection than splinterproof shelters are constructed for the troops.

d. Depth

German fortified zones are laid out deep enough to compel the attacking artillery and its ammunition service to change positions during the attack. The aim -is to deprive the attacker of surprise effect, and to cause him to lose valuable time, which may be used by the defender in organizing a counterattack.

If a limitation of funds does not permit the construction of a zone of uniform density that would fulfill the requirement of depth, the Germans construct two parallel fortified belts of maximum strength, separated by that distance which will insure maximum disorganization and embarrassment to the attacking artillery. The intermediate terrain between these belts is provided with permanent works, which, though lacking density, are so sited that progress through them will be slow and difficult. Field fortifications are also constructed in the intermediate area, and from them machine guns, antitank guns, and other infantry weapons supplement and reinforce the defensive fire. Obstacles of all types are employed extensively throughout a zone to delay and force the enemy to advance into a particular area that is best suited for defense.

The outpost area, which includes fortifications of all possible types, is also calculated to give depth to a German fortified zone, and to help in absorbing any surprise attack that is directed against the main position. The mission of troops in this area is to prevent the enemy from laying observed artillery fire on the main battle position, to delay his approach, and to inflict casualties. Part of the mission of German combat outposts is to prevent the enemy from conducting terrain and combat reconnaissance toward the main fortified belt.

3. FIRE CONTROL

a. Gapless Firing Chart

The basis for the defense of a main position in a German fortified system is the gapless firing chart. The effective field of fire of the heavy infantry weapons from their fixed positions is determined by the limits of their loopholes. Infantry weapons emplaced in field fortifications supplement this fire. The heavy infantry weapons also participate in harassing, destructive, and barrage fire according to their effective range, but their chief mission is defense against assault. If the enemy succeeds in driving back the advanced forces and the combat outposts and begins to attack the fortifications, the Germans open from the fixed positions a defensive fire based on data that was previously prepared and included in the chart.

The firing chart regulates the coordination and the distribution of fire of the weapons installed in the permanent and the field fortifications so that all areas in which an attack may occur can be controlled. Because loophole fire from permanent fortification is limited on the flanks, the Germans provide support, especially with machine guns, from field works.

The position from which enemy weapons may open fire against loopholes is estimated in advance by the troops manning each loophole. Mines may also be laid at appropriate points. The German firing chart is designed to guarantee a continuous belt of fire, even if individual fortifications are put out of action. Regimental commanders are responsible for coordinating

firing charts at the boundaries of the battalion sectors. The German firing chart is based on -a battalion sector, and sometimes separate charts may be set up for a fortification or a group of fortifications.

b. Distribution and Control of Fire

The decision to open fire is made by the battalion commander, or by the commander of a fortification or group of fortifications. The subordinate commanders of works may open fire independently as soon as they have received the "fire at will" order from the battalion or fortification commander. To stop the enemy early, the Germans prescribe that fire must be opened at long range in accordance with the data in the firing chart.

The weapons of a German permanent fortification do not remain inactive, not even while being fired on. They endeavor to delay the approach of the attacker immediately, and especially to prevent individual enemy guns from being emplaced. The weapons of the concrete works first engage from the flanks the most dangerous targets which appear in their combat sector, and, therefore, such works are provided with frontal protection by permanent and field positions. Targets in the sectors of other works are engaged only on the order of a superior commander, even though the targets seem worth-while.

Combat sectors are subdivided into gun sectors because in the six-loophole armored turrets of German fortifications the machine guns fire, as a rule, on separate targets. Because of the position of the loopholes, combined fire from both machine guns can be

employed only in exceptional cases, and then only at medium and long ranges. The fire is combined if the target is in range of both guns, and if a decisive effect can be attained.

By frequent and rapid change of targets, pillboxes fire on many targets in a short time, thus utilizing thoroughly the fire effect of the weapons. If a change of target necessitates a change of loopholes, the shift is accomplished by the machine guns successively, to avoid interruption of fire effect. Since mortars supplement the defensive fire of the machine guns, especially in broken terrain, close cooperation with the machine gnus in the bunkers is sought. Mortars installed in the field support the fire of the other heavy infantry weapons and the artillery in places where the effect of the latter two weapons is not sufficient.

Infantry guns open fire as soon and as heavily as possible. Their chief mission is to engage troublesome targets which cannot be reached by other weapons. In employing weapons emplaced in bunkers, the Germans open fire as soon as the enemy reaches the effective range of their flanking weapons. If a blinker is put out of action, the neighboring works take over its combat sector. By flanking fire they attempt to prevent any enemy penetration through the resulting gap, insofar as this is permitted by the effective range of their weapons and the necessity for defending their own frontal sector. German troops are taught that when a position is lost, flanking fire from neighboring positions may be decisive in repelling an enemy penetration.

c. Control of Machine-Gun Fire

Machine guns are the chief source of German infantry fire from combat positions. The commanders of positions direct the machine-gun fire in accordance with the combat orders for their position, and, as a rule, order direct laying on the strength of their own observations.

Targets to be engaged by machine guns in pillboxes are assigned by fortification commanders in accordance with the data furnished by observers in turrets or armored observation towers. If the designated targets cannot be seen from bunkers, or if the targets are screened by smoke, the observers take over control of fire also.

In six-loophole armored turrets, the gunners usually engage the target independently after the fire order has been given. Turret commanders supervise simultaneously the fire of both turret machine guns and observe continuously the entire combat sector.

4. ANTITANK DEFENSE

A German defensive zone is protected against tank attacks by natural or artificial obstacles which are covered by suitable antitank weapons of all kinds. In the outpost area, strong mobile antitank units are attached to the forces employed in the outpost area to deal with enemy armored forces.

The chief mission of stationary antitank guns of all calibers and of certain specially designated artillery in a German fortified zone is to destroy the medium or heavy infantry support tanks, which might attack the loopholes of works in a main fortified position.

Should the enemy succeed in penetrating the main fortified position, the Germans prepare for the appearance of strong tank forces in an afterthrust to widen the point of penetration. Should enemy tank forces attempt a further penetration of the main position, mobile reserves of antitank units, mobile engineer forces held in readiness with TellermineSj and mobile reserves of heavy and light antiaircraft guns of the Air Force commander are employed to engage them. In some situations the Grermans combine their divisional antitank battalions for uniform employment by the corps or higher command. In cases of immediate danger, the Grermans require their antiaircraft artillery to give priority to defense against tank attacks rather than air attacks.

If reinforcement of fixed antitank defenses in a fortified zone becomes necessary, the infantry antitank company is employed for this purpose in field positions among the fortified works. The antitank company in such a case is subordinated to the sector commander, as are the fixed antitank defenses. However, the use of infantry antitank units for the relief of permanent antitank defenses is considered exceptional. The German infantry company provides the necessary depth for the antitank defense of the regimental sector. Only in exceptional cases, as in terrain absolutely secure against tank attack and well protected by effective obstacles and a sufficient number of antitank guns, is the infantry antitank company to be used as a mobile reserve. Its disposition depends on its mobility and its ability to maneuver across country.

The fixed antitank weapons are manned and relieved by fortification antitank units.

Infantry antitank units using embrasured antitank emplacements, antitank guns employed in intermediate terrain, and antitank riflemen engage principally light and medium tanks. Heavy tanks are engaged by special antitank weapons, supported by artillery and combat engineers. Machine guns emplaced in the fortifications normally fire on enemy infantry, and also fire at the observation slits of the tanks.

5. ARTILLERY

German artillery in a fortified zone consists of position artillery, which is stationary or of limited maneuverability, mobile divisional artillery, and army artillery, used for reinforcement. The bulk of the defending artillery is highly mobile in order that it may be employed for mass effect at the point where the enemy attempts a decisive attack. Artillery positions are prepared in the outpost area throughout the fortified zone, and in rear of this zone for the maximum number of artillery batteries required. These positions are laid out as much as possible near defiladed routes of approach. The positions also include protection for men and ammunition, and have an underground communication system to previously established observation posts which are usually located in armored turrets-

In the initial stage of combat the bulk of the light and medium defending artillery is held in the advanced positions for counterbattery and counterprep-aration missions. If their defending artillery is

forced to displace by an attack that reaches the fortified zone, the Germans concentrate maximum fire on the enemy infantry in order effectively to prepare a counterattack. For this purpose, a certain number of batteries in the fortified zone are emplaced behind protection that can withstand the heaviest enemy artillery fire. Such batteries are permanently emplaced.

In case the counterattack fails and the defending divisional artillery is forced to evacuate the forward areas of the fortified zone, the Germans give this artillery the extremely important mission of concentrating its entire fire on the enemy infantry.

The Germans have laid down the doctrine that the closest liaison between. artillery and infantry and the local collaboration of artillery with all other branches of the service are decisive factors in the conduct of artillery combat and in the outcome of the defense. They prescribe that this cooperation must be established and maintained in every way. German artillery is trained to take the following deceptive measures:

a. Repeated changes of positions between missions.

b. Restricted activity from the firing position

chosen for the main decisive battle.

c. Individual missions and harassing fire are carried

out principally by changing the range and by roving

batteries.

d. A number of- silent batteries are held in reserve

so as to be available for special missions during enemy

attack.

6. OBSERVATION, RECONNAISSANCE, AND REPORTS

Constant observation of the terrain from all fortifications, before the approach of the enemy and during the attack, is regarded as of the utmost importance by the Germans. Observation is not permitted to lapse during pauses in fire, particularly during darkness or fog. In works which have no field optical instruments, observation is maintained through loopholes. In bunkers, armored turrets, and observation posts, standard fixed optical instruments are used for this purpose. Sufficient instruments are issued to permit extensive, gapless, and safe observation of the entire combat terrain.

All useful observations are reported at once to higher headquarters and passed along to the commanders of other fortifications. Furthermore, at times designated by higher headquarters, fortification commanders make brief daily reports, including—

a. Conclusions drawn from observations of the

enemy.

b. Engagements.

c. Combat strength and losses.

d. Condition of fortifications, weapons, and instruments.

e. Requisitions for replacements and supplies.

The chief mission of German army reconnaissance

aircraft attached to the corps general staff is to secure advance information about enemy preparations for attack. In large-scale fighting, the Germans use reconnaissance planes to clarify their own situation also. During quiet periods, such aircraft superintend

the camouflaging of finished combat installations, as well as those under construction.

Individual aircraft may be attached to German divisions for the purpose of aiding the artillery to adjust on rear enemy areas.

7. COMMUNICATION AND CONTROL

All commanders in a German fortified zone are kept fully informed at all times of the actual situation within their area of command. In an effort to insure a continual flow of information, the Germans try to maintain a communication system that will function without fail under the heaviest possible fire of the enemy. Usually a double cable system, buried beyond the effect of the heaviest air bombs and artillery shells, is employed in a stabilized position.

For the purpose of efficient command control, neighboring bunkers or turrets are united into a group or fortress by underground tunnels. In this way, the German Army tries to assure not only greater tactical control, but also greater tactical strength. Each fortress forms a battalion defense area in which the individual forts are capable of mutual support. The bunkers with maximum observation and fire power are the focal points of the new system, and are provided with complete flanking fire from fortifications within the group or from additional bunkers constructed for this purpose. Wire obstacles covered by this flanking fire are camouflaged as carefully as possible in order not to betray to the attacker the positions of flanking bunkers and the battalion defense areas.

Section III. EXCERPTS FROM " THE STABILIZED FRONT"

8. GENERAL

The Germans teach that defensive combat on a stabilized front is conducted generally according to the same principles as the defense in a war of movement, the chief consideration being the tactical organization of the defensive fires and forces. The stabilized front consists of an outpost area and one or more continuous main areas of fortifications in depth. Within the meaning of the term "stabilized front," the Germans include zones-of permanent fortifications constructed in peacetime, like the West Wall, and fixed positions assumed through necessity during the course of a campaign.

The extent of construction in a German stabilized position depends upon the operational importance of the entire front and the tactical importance of the individual sector, the terrain, and the mission of the fortifications. The maintenance and repair of all works during battle are the responsibility of the crews and troops employed in them.

The subject of the fixed position is covered in "The Stabilized Front" {Die Standige Front) which is the designation of German Field Manual 89, printed in tentative form by the Government Printing Office in Berlin in 1939.

Much of the material contained in the manual is obsolete, the Germans having adapted their doctrine

to the tactical lessons learned on the battlefield since 1939. However, certain revealing principles of fortification have been digested and included in this study. In this section are quoted parts which are applicable to a study of German zone fortifications.

9. OUTLINE OF BATTLE ORDER FOR BATTALION SECTOR

a. Evaluation of Terrain for Enemy Attack

(1) Disposition of troops.

(2) Observation posts.

(3) Weapons for loophole firing.

(4) Terrain secure from tank attack.

(5) Points of main effort of hostile attack.

b. Firing Chart

(1) Section of 1/25,000 map with range sketch.

(2) Orders for individual weapons.

(a) Sectors of observation and effectiveness for

long-range fire—Opening of fire—Harassing fire.

(b) Sectors of observation and effectiveness for medium and close range—Opening 'of fire.

(c) Preparation for fire concentrations upon critical

terrain—Destructive fire.

(d) Regulation of fire of silent weapons as to time

and sector.

(e) Time and space specifications for barrage—Employment of ammunition—Justification and means for

opening barrage.

(f) Defensive fires on enemy penetrations—Support of counterattacks.

(g) Artillery observation posts—Communications with artillery.

(h) Line before which an enemy tank attack must be caused to fail.

c. Main Line of Resistance

(1) Sector boundaries.

(2) Type and location of obstacles.

d. Combat Outposts

(1) Mission and strength.

(2) Destination and route.

(3) Authority to issue orders.

e. Reserves

(1) Possible employment and routes.

(2) Time schedule.

f. Command Posts in Sector

g. Channel of Communication

Sketch supplied by commander.

h. Map—Composition of Armed Works in Each Company Sector

(1) Loophole emplacements.

(a) Machine guns.

(b) Antitank guns.

(2) Bunkers.

(a) Machine guns. (&) Antitank guns.

(3) Armored loophole turrets—Type and number

of loopholes.

(4) Armored mortar turrets.

(5) Observation installations.

(a) Map—Location and capacity of dugouts.

(&) Supplementary fixed weapons.

i. Ammunition Supply

Types and amounts.

j. Additional Garrison for Positions

(1) Strength.

(2) Weapons.

k. Emergency Alarms

(1) Alert.

(2) Gas.

(3) Air raid.

I. Administration

Rations.

10. OUTLINE OF COMBAT INSTRUCTIONS FOR AN INDIVIDUAL WORK

Combat instruction for of the Company.

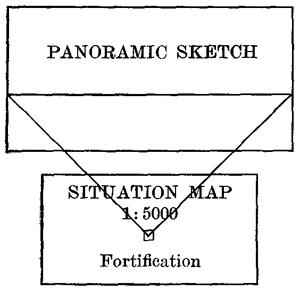

a. Panoramic Sketch

(On the panoramic sketch are entered the important terrain features and aiming points in the combat sector of the fortification. Each feature and point are given a designation.).

b. Combat Order

(1) Individual weapons in the fortification.

(2) Outer defense of the fortification.

(3) Troops occupying intermediate terrain.

(4) Execution of counterattacks.

(5) "Withdrawal of combat posts.

(6) Scouts between the works.

(7) Type of fortification and adjacent works.

(8) Nearest commander.

(9) Fortification cable net.

(10) Channels of communication.

(11) Distribution of garrison.

(12) Observation posts.

(13) Supply.

(14) Emergency regulations.

c. Range Card

d. Property List

(1) Fixed weapons.

(2) Ammunition supply and replenishment.

(3) Light and signal equipment.

(4) Emplacement equipment.

(5) Reserve rations.

11. SIGNAL COMMUNICATIONS

a. General

A dependable system of signal communications is of decisive importance for combat on a permanent front. Effective leadership would be impossible without it, and besides, it serves to strengthen the combat morale of personnel in the organized positions.

Before taking any tactical measures whatever, leadership must have the assurance that all signal communications are effectively established. As far as possible, changes in troop dispositions should not be made

until the necessary changes in signal communications have also been made.

b. Duties of Staff Signal Officer

The army signal officer, on the basis of instructions received from the signal officer of the army group command, issues directions for the use of the facilities of the G-erman Postal Service throughout the army area, in addition to supplying signal building material and equipment, and exercising control over further development of the signal network in the fortified positions. The army signal officer, in cooperation with the army quartermaster, likewise takes responsibility in advance for keeping communication equipment and spare parts for troops and fortifications at the army communication dump and in storage depots. He will also be responsible for delivering the equipment to the various organizations.

The corps general staff is responsible for the communication net in organized positions throughout the corps area. Special instructions concerning signal communications will be required when there is a change of sectors, when a new unit is brought into the position, and when communications between divisions are needed across sector boundaries.

The following are placed under the army communication officer:

(1) The army corps communication battalion (the army corps communication officer is the commanding officer of this battalion), and the fortification's communication staff, as well as attached platoons and details.

(2) The communication officer of the fortification's

pioneer (engineer) staff (it is his duty to provide and

maintain technical equipment for communications

within permanent fortifications, and also to cooperate

in the construction of buildings required for communications, such as blinker signal posts).

(3) The division communication officer (he is responsible for the communications net within the area assigned to the division; it is his duty to keep the corps signal officer currently informed on the state of maintenance and changes in the permanent net of the area).

On a stabilized front uniformity is absolutely essential in managing the net of communications throughout the division, even within the subordinate units. The communication officers of the individual units must cooperate with the division staff communication officer.

Staff and unit signal officers must familiarize themselves with the most important communication channels overlapping the neighboring sectors.

c. Fixed Communications on a Permanent Front

Fixed wire communication channels constitute the basis of signal communications on a permanent front. As compared with lines established to meet field conditions, these permanent lines are considerably better protected from enemy fire and interception, and they assure the transmission of orders between the fortifications and areas close to the rear.

As a safeguard against enemy action, all of the most important telephone communications should be dupli-, cated. Advanced positions, advanced observation posts, and combat outposts in permanently organized fortifications are as a rule connected by ground cable with the net of the battle position. Defense works, heavy infantry weapons, and batteries in the advanced area will have to rely on signal communications equipment in the possession of the troops themselves, or upon the telephone net of the German Postal Service.

To facilitate the finding of the buried ground cable, a weather-resisting, orange-colored recognition band 2 centimeters (eight-tenths of an inch) in width is placed above the cable at a depth of about 0.40 meter (1 foot 4 inches). Proceed carefully when digging! The trace of the cable is indicated on the ground by stones used as cable markers.

d. Utilization of German Postal Service

The instructions in this paragraph apply not only to the German Postal Service net, but also to privately established telephone nets such as mine and forest systems. Decisions concerning utilization of the German Postal Service net are made by the army signal officer. The signal officer of the corps staff applies to him for connections for long distance and local wires, for the corps as a whole and also for the individual divisions.

e. Artillery Net

The most important lines are those connecting observation posts with firing positions and alternate firing positions, and those connecting the infantry with the artillery. Battalion command posts are connected by telephone lines with all observation posts of their sec-tor, with the command posts of neighboring battalions, and with the higher artillery headquarters.

f. Sound-ranging Net

Sound-ranging nets are established by means of special cables which may not be used for purposes of conversation. Each observation post is linked with its plotting station by a telephone line for its exclusive use, and each sound-ranging station is connected with its plotting station by means of an exclusive sound-ranging wire. Each plotting station will require at least two telephone lines to link it with the observation battalion.

g. Flash-ranging Net

There is no necessity of keeping this net in special cables. Otherwise, the structure of this net corresponds to that of the sound-ranging net; flash-ranging connections constitute, therefore, part of the general net.

h. Infantry Net

There are direct lines connecting the division command post with each infantry regiment. The rear tie line is located at about the same depth as the infantry regimental command posts. It is used especially to maintain connections with the artillery, and to link infantry regimental command posts with one another. The rearward net is screened at approximately the depth.of the infantry regimental command posts.

There are, in addition, special lines to the battalion command posts. The frontward tie line is located approximately at the depth of the battalion command posts. It is used for connections between the battalions, between infantiy and artillery, and among different artillery organizations.

Each company commander is linked by telephone connections with his platoon commander, and the platoon and section commanders in turn are given a connection with their command posts. As a rule, the various command posts are linked together by groups. Party lines are most commonly used for these connections.

i. Duplication of Communications

The following can be used to duplicate parts of the signal nets:

(1) Radio.

(2) Heliograph.

(3) Blinker apparatus.

(4) Ground telegraph, equipment.

(5) lUuminants and signaling devices.

(6) Messenger dogs.

(7) Carrier pigeons.

j. Ground Telegraph Equipment

With the aid of this equipment it is possible to maintain communication over cables that have been severed by artillery fire. But since it affords no security against interception, this equipment has to be used very carefully. For that reason ground telegraph may not be used without the consent of the battalion commander. Report of its use should be made promptly to the division signal communication officer.

k. Illuminants and Signaling Devices

Organized battle positions are at present equipped not only with the army's usual illuminants and signaling devices, but also with a special emergency signal to be used by the garrison only in case of distress (this emergency signal equipment is in the course of development).

l. Messenger Dogs and Carrier Pigeons

The following principles apply to the use of messenger dogs and carrier pigeons:

(1) Messenger dogs are to be provided for areas in

front of the regimental command posts. They are

assigned to scout squads on reconnaissance duty. The

messenger dogs may also be used on clearly visible

terrain, on terrain that is difficult to cross or that is

exposed to strong enemy fire, or under circumstances

where alternate means of communication are not suit

able. Depending on their memory for places, messenger dogs can be used for distances up to 1.5 kilometers

(nine-tenths of a mile) and on artificial trails for

distances up to 3 kilometers (l%o miles).

(2) Messenger pigeons from permanent pigeon

posts will be assigned to the various fortifications,

shelters, and combat outposts, and possibly also to the

platoon assigned to reconnaissance of enemy signal

communications; or else they are turned over to scout

squads for use on their missions. The pigeons are

released in flights of 2 or 4. A messenger pigeon post has about 300 pigeons. Of this number, up to 10 pigeons are to be left at each shelter and about 30' at each fortification.

(3) Telephone communication must be assured between the permanent carrier pigeon posts and the division command posts. Reports turned in at the division command post are passed on from there to the various duty stations concerned.

m. Transfer of Nets to Relief Units

When a relieving unit moves into the position, the new signal units should establish advance detachments at least 24 hours ahead of time. The signal personnel to be relieved should not be taken out until the new personnel have adapted themselves to the new position. Documents pertaining to radio operation and codes (including code names for telephone and blinker communication) should be taken over unchanged by the newly arrived troops to conceal the fact that there has been a relief. Change of personnel and of radio and code instructions must never be effected at the same time.

n. Maintaining Communications While Changing Sectors

Staff and unit communication officers, as well as permanently assigned signal personnel, must keep informed about the signal situation in the neighboring sectors in order to make it possible at any time to change sector limits without disrupting communications. Each unit concerned should place at the disposal of its neighbors a record of its own signal

system. The circuit sketches of each unit must show connections across sector boundaries.

In some circumstances it may be advisable, for regiments transferred from their own to neighboring divisions, to depend temporarily on the connections of their former headquarters.

Connections that are not actually required for combat purposes should be dispensed with. Emphasis should be placed on the establishment of continuous transverse connections and on the linking of combat posts, the principal observation posts, and the battery firing positions.

o. Supplementing a Permanent Cable Net

In view of the danger of interception and the need for repairs, the use of field service lines to supplement the net of the permanent position should be kept at a minimum. Simplicity of arrangement is a requirement in adding these supplementary lines. Every precaution must be taken to insure that the net can be kept functioning by available personnel under heavy fire. Lines constructed by unit signal personnel must be checked by the division signal communication officer.

p. Maintenance and Repair

In the course of a defensive battle, it will not always be possible to keep all lines hi order. In that event all available signal personnel will be used to reestablish the most important lines, giving up those lines which can be spared. Precedence must be given to maintenance of transverse connections and of the most important of the lines extending toward the front, such as those to command posts and observation posts.

q. Signal Intelligence Platoons

Signal intelligence platoons or platoons assigned to reconnoiter enemy signal communications should be employed according to tactical points of view- They should also be continuously informed and kept under continuous guidance. Furthermore, they should be furnished with information obtained by other reconnaissance units. Intelligence platoon leaders must continually endeavor to improve the training of their noncommissioned officers and men and to impart their experience to them. They should point out that their missions are of great importance even though the results attained may be slight.

The platoons covering enemy signal communications will receive, from the listening company in whose area they are located, directions to guide them in their reconnaissance work. The listening company will also report to the platoon the results of its reconnaissance of the division zone to which the platoon belongs.

Details ascertained by reconnaissance should be kept on file as permanent reeordsf both in sketches and on index cards. Results canf as a rule, be obtained only from a comparative study of the details. Information should be exchanged with other types of reconnaissance units, such as the observation battalion. It is useful to exchange with neighboring divisions the results of reconnaissance covering enemy communications and the experience acquired. It is the duty of the army staff communication officer to assure cooperation between the listening companies and the reconnaissance platoons.

Important information, such as the appearance of tanks and other new units, relief of units, preparation of missions, and the effect of fire directed against the enemy, must be relayed at once to the nearest troops and to the division. The results obtained by reconnaissance platoons covering enemy communications should also be sent to the listening company. Steps must be taken to assure prompt and reliable transmission of information. Messenger pigeons are among the means of communication suited for this purpose. When messages are of great importance, several pigeons should be dispatched with the same message.

r. Radio Intelligence

It is the duty of radio intelligence troops to monitor radio communications of advanced enemy units. Enemy radio communication from division headquarters to the rear and radio communication between planes are monitored by fixed listening posts, listening companies, and listening posts of the air forces.

The range of enemy apparatus whose messages are to be intercepted is in many instances not in excess of a few kilometers. For that reason radio intelligence detachments must be placed well forward.

s. Wire Communication Intelligence

Valuable information may also be obtained by wire communication intelligence even though the results

seem trifling. It is possible suddenly to intercept important information. The chances are especially good if the enemy's loop circuits have been damaged by cannon fire.

Where there is a lack of permanent signal installations, the newly arrived units themselves must set up temporary telephone interception posts. Dugouts of permanent construction are well adapted for use as telephone interception posts. If jnines are embedded in the areas chosen for telephone interception installations, the lines should be placed in passages that are free of mines, so as to make it possible to provide for upkeep and repairs without danger. The closest cooperation with the local engineer commander is absolutely essential.

t. Protection against Interception

In view of the fact that signal installations on a stabilized front are fixed, there is a danger of their being tapped. All possible measures must be taken, therefore, to prevent the enemy from enjoying the advantage of effective reconnaissance of communications.

In the event that the enemy makes a breakthrough, lines leading in the direction of the enemy should be disconnected. When the advanced position is abandoned, lines leading into it should also be cut off. Similarly, when the enemy has broken into the main battle position, lines leading to works which are unmistakably held by the enemy should be disconnected.

Part 2 GERMAN FORTIFIED SYSTEMS

Section IV. INTERIOR AND COASTAL DEFENSES

12. GENERAL

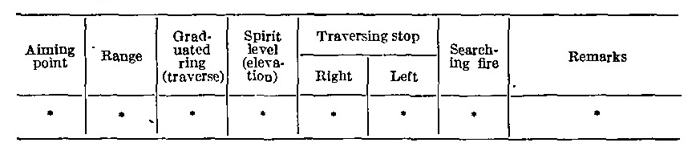

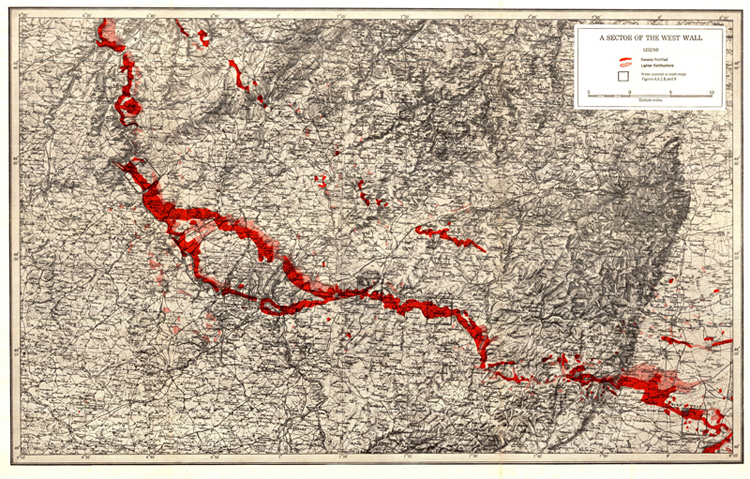

Germany possesses elaborate fortifications on her own coasts and the coast lines of occupied countries, as well as in the interior and on land frontiers in regions where fortifications have offensive or defensive value. The sea frontier fortifications extend from Memel to Emdeii on the coast of Germany proper, and from Emden along the occupied coasts of the Netherlands, Belgium, and Erance to the Spanish border. The general location of the principal land and coastal fortification systems in western and eastern Europe are shown on the map, figure 1.

Map. Figure 1. —German fortified systems, western and eastern Europe.

13. ORGANIZATION OF COASTAL DEFENSES

The coastal installations are Germany's first line of defense against invasion. The original German coastal fortifications were constructed, manned, and defended by the Navy in conjunction with the Air Eorce. However, new fortifications and improvements of old defenses on the German and the conquered coasts have been added since 1940 under the direction of the Army. In the absence of information to the contrary, it is presumed that the original naval fortifications on Germany's own coast line are still serviceable and probably greatly reinforced. They are administered by two naval territorial commands, the "North Sea Station" and the "Baltic Station." Under the commanding admiral of each station is a subordinate admiral, known

as the ''second admiral/' in direct charge of the fortifications.

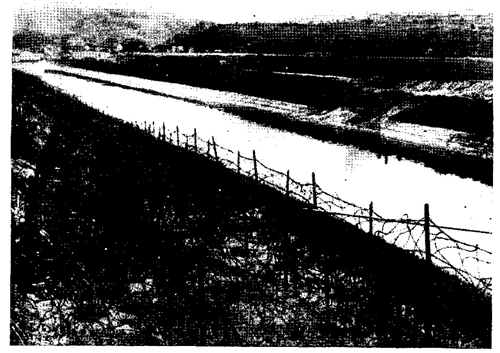

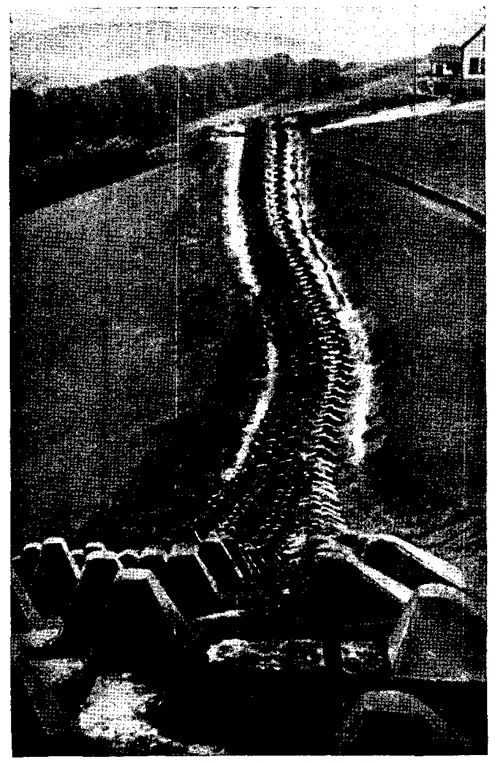

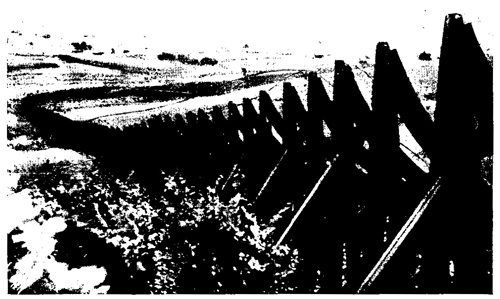

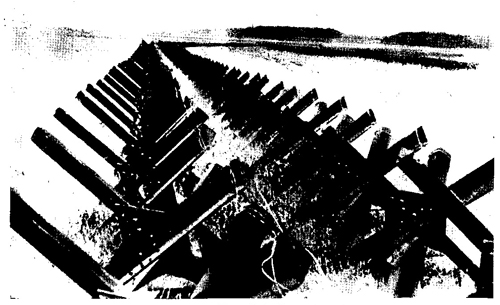

Germany's coastal defenses begin with obstructions in the water and extend inland, their strength and depth depending on the suitability of the beaches for hostile landings, the natural defensive strength of the terrain, and the strategic value of the portion of coast line concerned. In many cases the defenses reach depths of 35 miles from the coast. Many concrete emplacements, shelters, and other installations have been built along the possible landing beaches and around important ports; and the former French, Belgian, and Dutch defenses have been integrated into the German fortified system. Other installations, which the Germans have been busy constructing or improving for more than 3 years, are long-range fixed and railway guns, mobile coast-defense batteries, elaborate antiaircraft emplacements, prepared positions for holding forces at all vulnerable points, and extensive water and beach obstacles.

For a detailed study of the types of installations on the occupied coasts of Europe, see "German Coastal Defenses," Special Series, No. 15 (15 June 1943).

In the German coastal defenses in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, the smallest self-contained unit of the infantry positions is the shell-proof "defense post" (Wider standsnest), which normally includes machine guns and occasionally antitank or infantry guns, and is held by a group of less than a platoon. A number of such defense posts, adapted to the terrain and affording mutual support, make up the familiar German "strongpoint" (Stutzpunkt). Each strongpoint

has all-around protection by fire, wire, and mines, and is provisioned to hold out for weeks if isolated. The coastal strongpoints are manned by units of company or larger size, and their armament includes the heavier infantry weapons. There are also naval. Air Force, and artillery stongpointsj which are usually centered on antiaircraft batteries or signal installations. Strong-points are further combined into powerful fortified groups (Stutzpunktgruppen), and in such combinations the groups include underground or sunken communications for the defense of particularly vital sectors. Such strongpoints include antiaircraft guns and heavy antitank guns, in addition to other weapons. Finally the defenses are organized into divisional coastal sectors (Kustenverteidigungsabschnitte).

14. WESTERN INTERIOR DEFENSES

a. From the Coast to the Maginot Line

Eeports of German fortifications in the area between the Atlantic .coast and the German frontier do not fully agree upon their nature and extent. However, it is certain that the Germans have taken advantage of the succession of excellent natural barriers formed by the French river system. These natural lines have been strengthened with both field and permanent installations, and particularly with obstacles of all types. Key terrain throughout the area no doubt has been strengthened in every possible way. Individual fortifications, which are not laid.out as densely as in the West Wall and follow no apparent zone system, have been reported in great numbers, particularly in the neighborhood of communication centers. Available information on the distinguishable lines is indicated on the map, figure 1.

b. The Maginot Line

By the terms of the armistice between Germany and France the Maginot Line became a part of the German western defenses. All reports agree that some portions of the Maginot Line have been abandoned while others which are strategically and tactically useful to the Germans are being steadily reinforced and incorporated into the West Wall system.

Reports that the Maginot Line has been altered to face westward are patently false, since most of the French works were sited on forward slopes facing eastward. It can be assumed, however, that every effort has been put forth by the Germans to incorporate useful French fortifications into their West Wall system, and that those works which camiot be used offensively will serve as an additional, highly developed band of concrete and steel obstacles in front of the West Wall itself.

15. EASTERN LAND DEFENSES

a. Eastern System

The German "Eastern System" of fortifications, which faces the Polish provinces of Posen and Pom-erania, is a deep zone of modern, permanent works. It was built primarily as a strategic base for operations in Poland, and secondarily as security for Germany's rear dining operations in France and the Lowlands. The keystone of the "Eastern System"

is a quadrilateral area due east of Berlin on the Polish frontier, measuring about 40 miles long from north to south and 20 miles from west to east. Because of its shape and the river on which it is based, it is also known as the "Oder Quadrilateral." This system, by providing security for the German center during the Polish campaign, effectively prevented any Polish movement against Berlin, and permitted the Germans to mass the bulk of their armies on the Polish flanks in German Pomerania, in Prussia in the north, and in Silesia in the south. Without this system as a pivot, the Gei'man Army could not have executed its bold double envelopment of the Polish armies without the greatest risk.

The Oder Quadrilateral is reported to be supplemented by minor belts of permanent works in Pom-erania, north of the Netze River, and in the vicinity of Schneidemiihl, and in Silesia, northeast of Glogau and Breslau. There is no available information as to their extent.

b. Slovakian Treaty Line

By virtue of a "treaty" concluded between Germany and Slovakia in March 1939, Germany was given the right to fortify the White Carpathian mountain range to a depth of 30 miles within Slovakian territory. It is not known whether this system has actually been built.

c. The East Wall

A report dated February 1943, states that, a new "Ostwall" system of fortifications, planned and recommended by the German High Command, had been approved for construction. There is no definite evidence that construction has been started, nor of the nature of the proposed fortifications; however, the general areas that were covered by the treaty are shown on the map, figure 1.

d. East Prussian System

The East Prussian fortifications appear to have been started secretly during the Versailles Treaty era, and were greatly strengthened during 1938 and 1939 by the addition of many forts, individual bunkers, blockhouses, tank obstacles, and wire entanglements. The strategic purpose of the system was similar to that of the "Eastern System"; in addition, it was expected to protect industries in East Prussia.

The East Prussian works may be divided into two groups: one facing south against Poland, the other running in a north-south direction along the general line of the Angerapp River. The fortified area of Lotzen forms the junction of these two lines. In the southern system, a very large number of "bunkers" were observed under construction late in 1938, and therefore the strength of this part of the line is believed to be great. This southern system extends along the general line of Osterode—Tannenberg— Ortelsburg—Spirding See—Lotzen.

Section V. THE WEST WALL

16. SCOPE OF THE SYSTEM

a. General

The West Wall, the principal system of German fortifications, faces a part of the Netherlands, Belgium. Luxembourg, France, and a part of Switzerland. It was intended to serve as the base for offensive operations against the western powers and to provide strategic defense during operations in the east. Secondarily, the system had the defensive role of protecting vital industrial areas, such as the iron and coal mines of the Saar; the lead and zinc mills in the southern Schwarzwald; and the industrial areas of Ludwigshafen, Mannheim, and the Rhineland.

Late in 1942 the German Defense Ministry established a Western Defense Command to take over control of both the West Wall and the Maginot Line.

One-third of all the construction facilities of Germany and more than 500,000 men were concentrated on the task of constructing the West Wall. The great majority of these men were civilian workers, but troops were used on roads, camouflage, signal communications, and field fortifications. The project was carried out by the Organisation Todt, a semi-military construction corps, which began the work in 1938. The Todt organization controlled 15,000 trucks during the construction operations. At the outbreak of war in September 1939, 6,000,000 tons of concrete,

260,000,000 board feet of lumber, and 3,000,000 rolls of barbed wire were among the materials already used in the fortifications.

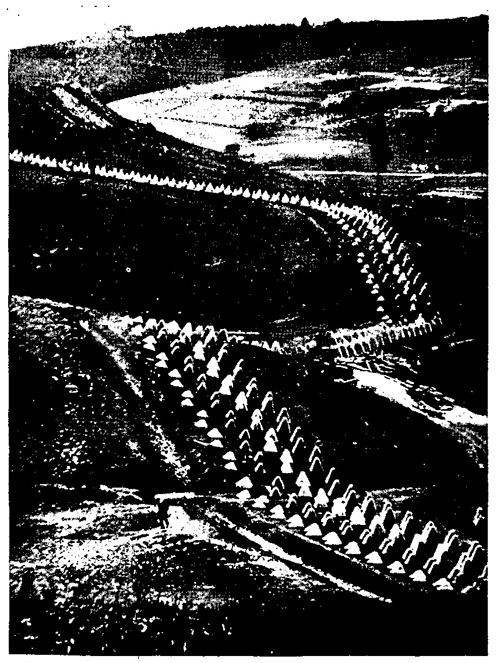

The depth of the fortified areas of the West Wall ranges from 8 to 20 miles. The length of the line is about 350 miles. Within these limits the whole great project in 1939 encompassed 22,000 separate fortified works—which means an average density of about 1 fort on each 28 yards of front. The average distance between works, in depth, is 200 to 600 yards. The actual spacing of the works depends, of course, on the nature of the terrain, and U. S. observers who have visited some parts of the fortifications have reported that the space between them varied from 200 to 1,000 yards.

These figures are merely statistical and are useful only in giving an idea of the vastness of the project. A full appreciation of the military value of the West Wall can be gained only by considering the tactical and strategic layout of its zones and component fortifications in relation to the terrain and the mission for which they were designed.

b. Distinguishable Lines

The West Wall consists of a series of deep fortified zones rather than a line of forts and includes individual steel and concrete works, field entrenchments, belts.of wire, and tank obstacles. An example of the actual outline of these zones, showing how they are adapted to the terrain, is shown in figure 2 (facing p. 142), which is a map of a sector of the West

Wall. The following individual fortified lines may be distinguished in the West Wall system:

(1) The "Rhine Line" runs from a point south of

Karlsruhe to Basle.

(2) The "Black Forest Line" is a reserve position

for the "Rhine Line" along the crest of the Black

Forest (Schwarzwald).

(3) The "Saar-Pfalz Line" extends from a point

on the Moselle River southwest of 'Trier through

Saarburg—Merzig—Dudweiler—St. Ingbert—a point

south of Zweibriicken—a point south of Pixmasens—Bergzabern—Bienwald.

(4) The "Saarbriicken Line" is an advanced line,

in front of the "Saar-Pfalz Line" extending through

Merzig—Saarbriicken—St. Ingbert.

(5) The "Hunsriick Line" is a reserve position for

the "Saar-Pfalz Line," extending from a point just

east of Trier through St. Wen del—a point south of

Landstuhl—Landau—a point on the Rhine south of

Gerniersheim.

(6) The "Eifel Line" runs from the junction of

the Moselle River and the Luxembourg frontier at

Wasserbillig, along the Luxembourg frontier to its

junction with Belgium—thence along the crest of the

Sclmeifel hills to Schleiden.

(7) The "Aachen Positions" consist of two lines.

An advanced line runs from Monschau through Rotgen—a point due east of Aachen—Herzogenrath,

north of Aachen, at which point it joins the main line.

The main line extends from Schleiden through Steck-

enborn—Stolberg—Herzogenrath.

(8) The "Holland Position" extends from Her-zogenrath through Geilenkirchen—a point east of Erkelenz—a point 12 miles due west a£ Munich-Gladbach.

17. ZONE ORGANIZATION

The West Wall is divided into zones of defensive belts in depth, especially in terrain which favors an enemy attack. This is a part of the German doctrine of defense.

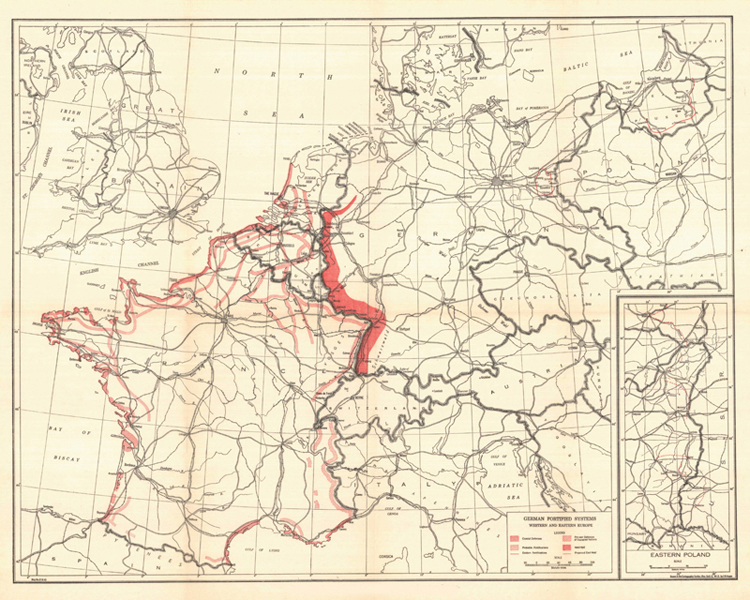

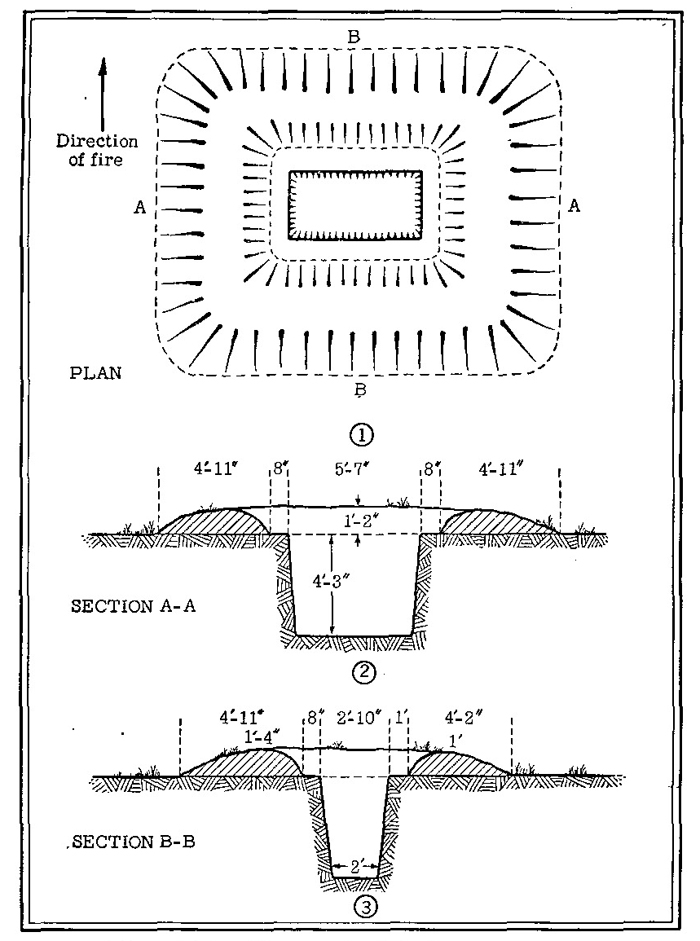

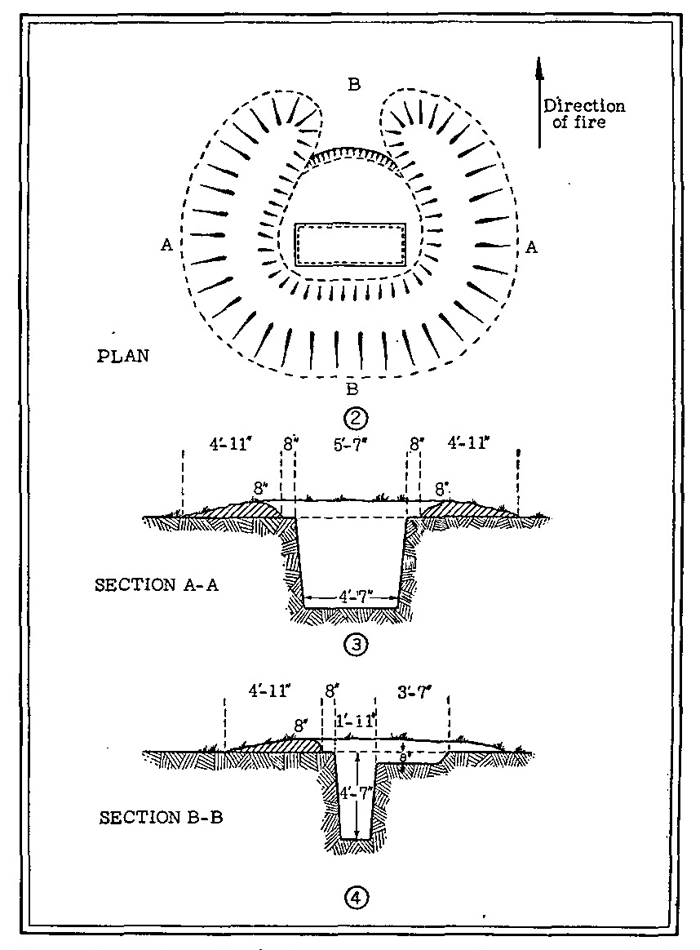

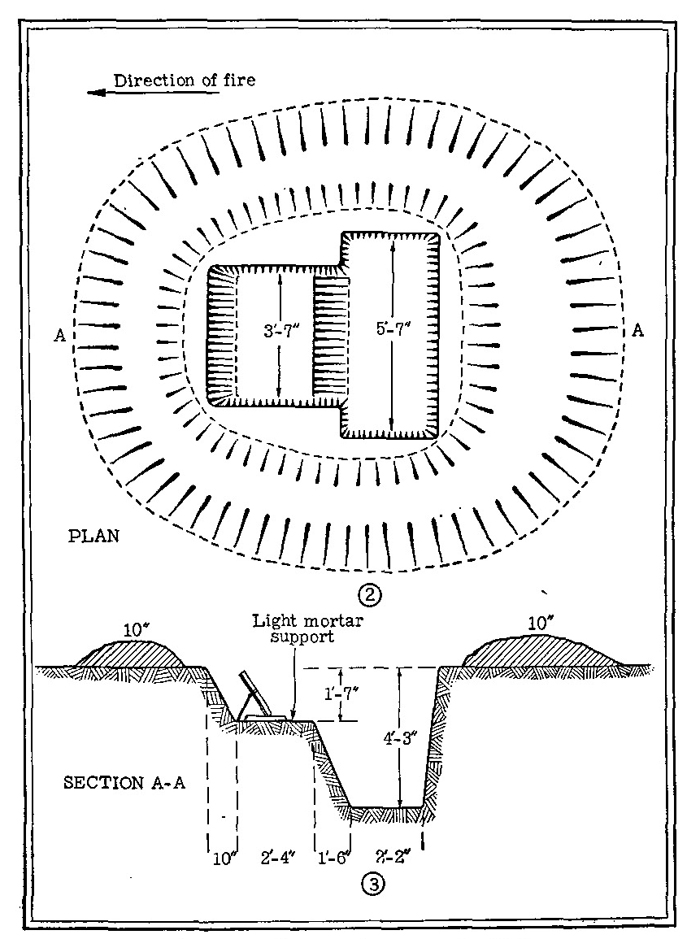

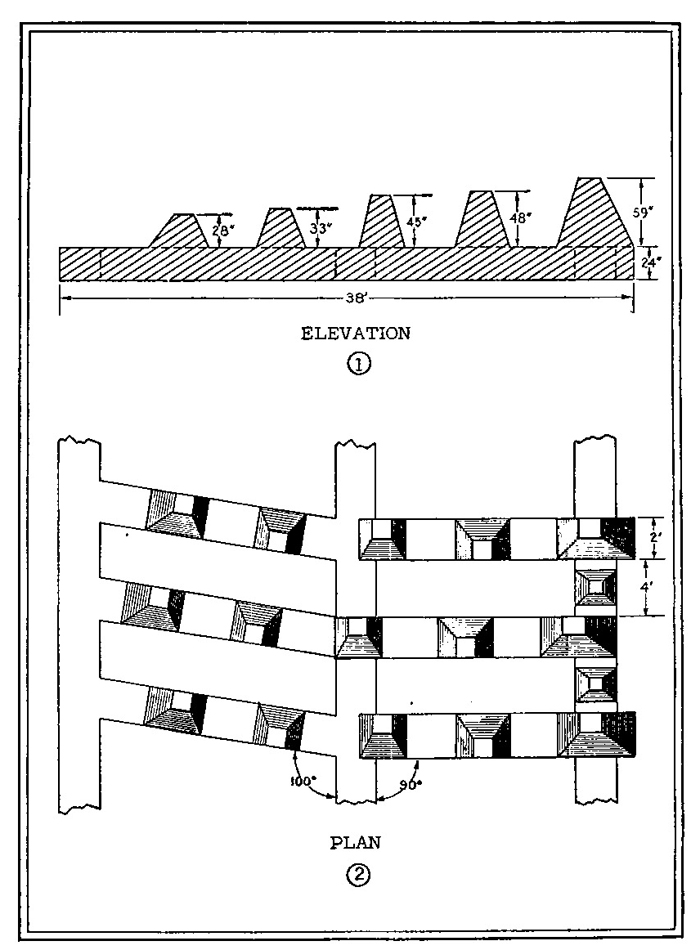

A sector of the West Wall will normally consist, in the order named, of the following four areas (see fig. 3) :

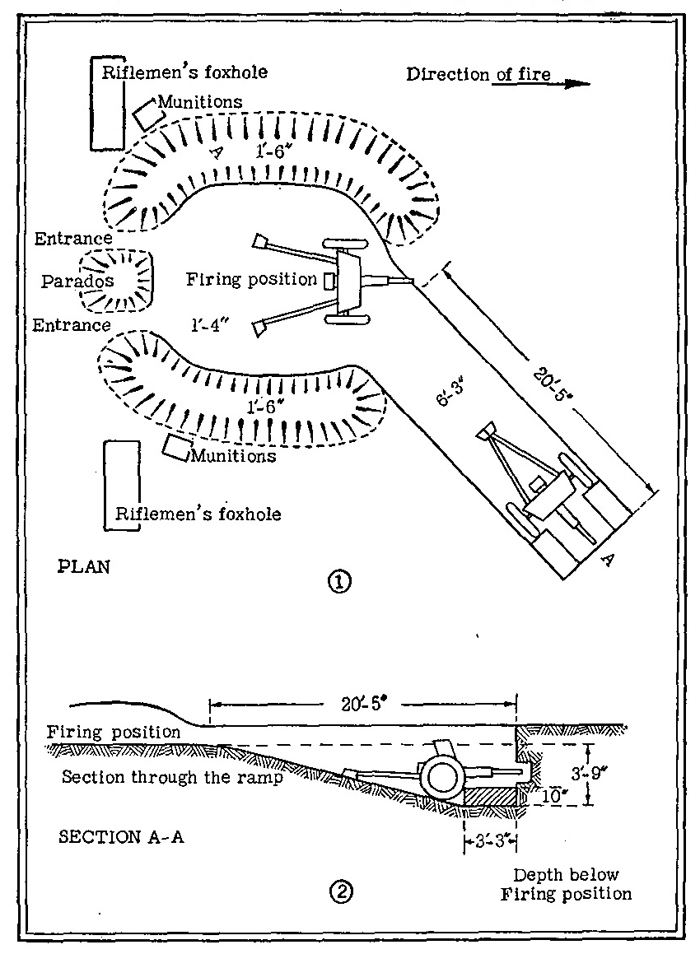

a. Advance Position (Field Fortifications)

The advance position is an area of field fortifications, including trenches, barbed-wire entanglements, machine-gun emplacements, observation posts, and artillery emplacements.

b. Fortified Belt

This belt is from 2,000 to 4,000 yards deep, and consists of concrete and steel works and artillery emplacements the weapons of which completely cover the zone area with mutually supporting fire. The forward boundary of this belt is 5,000 to 10,000 yards in the rear of the advanced position.

c. Second Fortified Belt

This belt is similar to the first, but in general it is not so strong. It is located 10,000 to 15,000 yards in the rear of the first fortified belt. In the intermediate terrain between the two fortified belts, fortified works are located at critical points on natural avenues of advance.

Figure 3.—Organization of a fortified zone.

d. Air Defense Zone

The air defense zone comprises the first and second fortified belts and an area extending from 10 to 30 miles in rear of the second belt. This constitutes the so-called "ring of steel" around Germany. This zone has antiaircraft defenses throughout, but the greater part of the antiaircraft materiel is in the area behind the second fortified belt. An efficient warning system is maintained, and attack planes and balloon barrages complement the antiaircraft artillery.

The massing of the major part of the antiaircraft defenses in the rear of the second fortified belt, the Germans believe, produces optimum results by making possible the concentration of the bulk of antiaircraft fire on hostile aircraft.

It is not believed, however, that all areas of the West Wall are divided invariably into a fixed number of belts. The defenses are adapted to local topography. Where the terrain is defensively strong, as for instance in the Vosges Mountains, only a minimum development of artificial works will probably be found. But it must be emphasized that in the natural avenues of invasion into Germany the zone organization of fortifications will be encountered in great strength.

18. DETAILS OF A ZONE

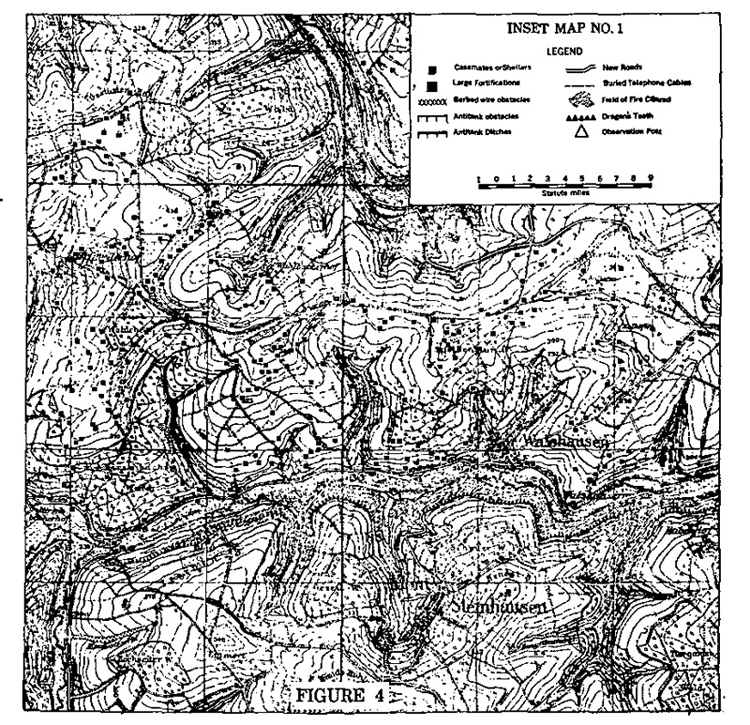

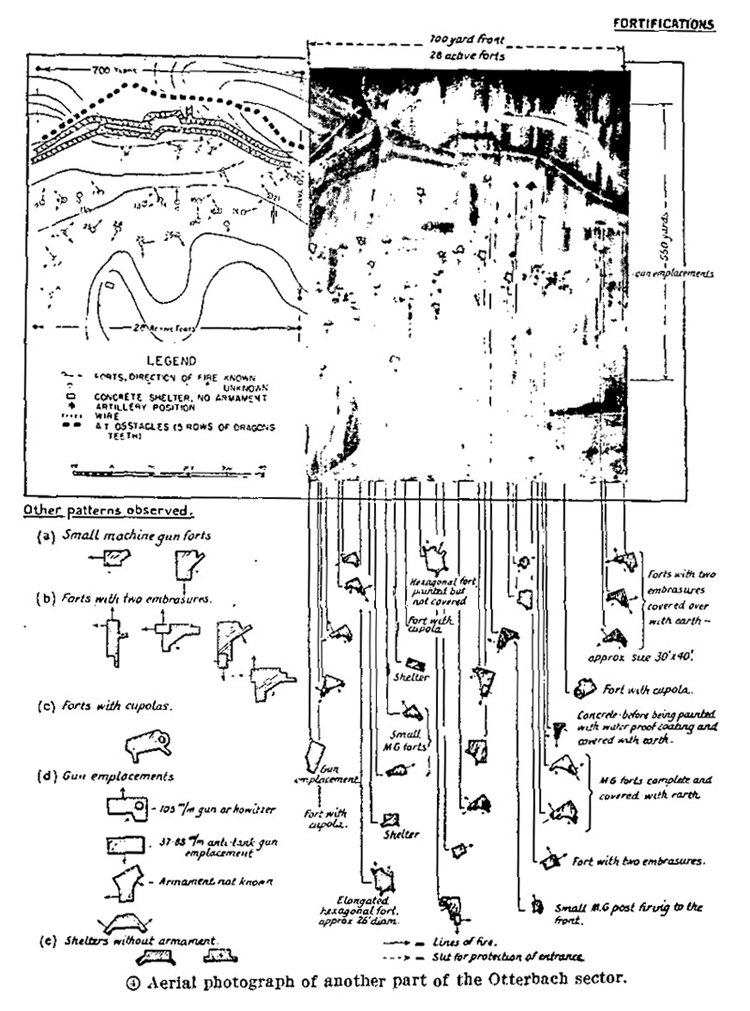

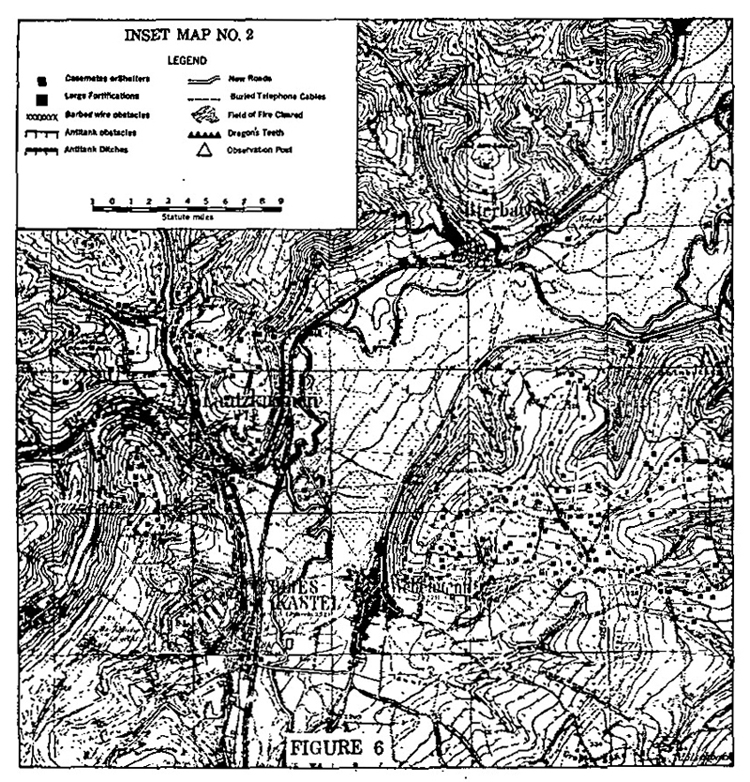

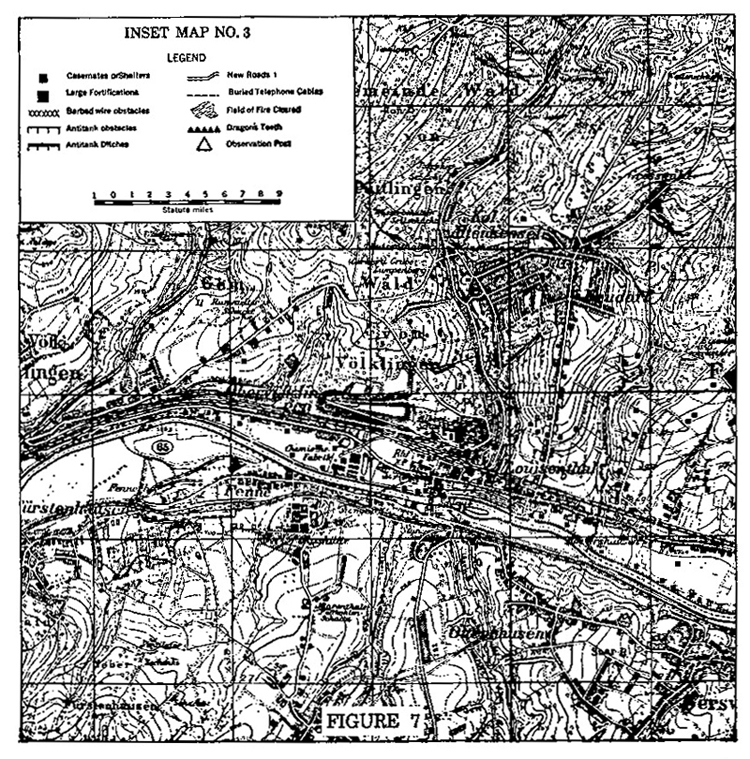

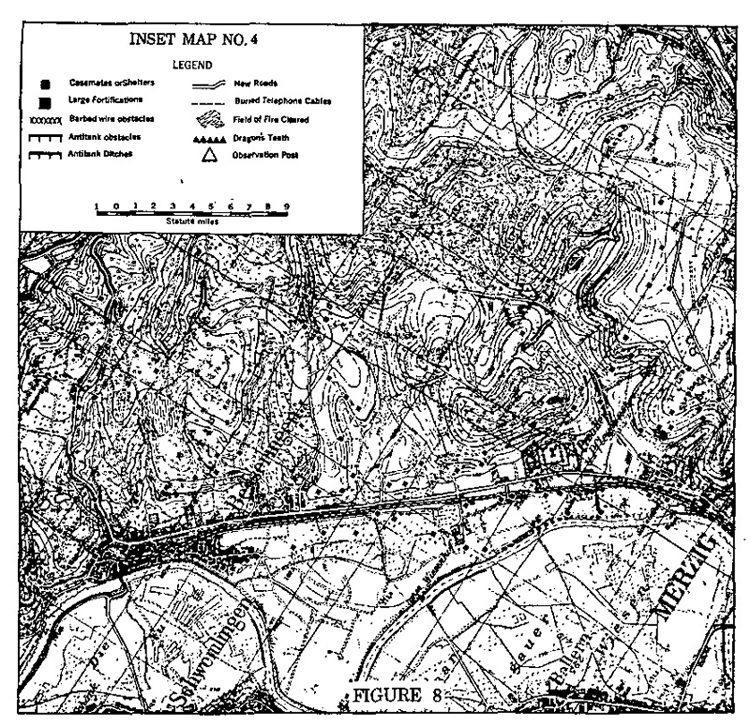

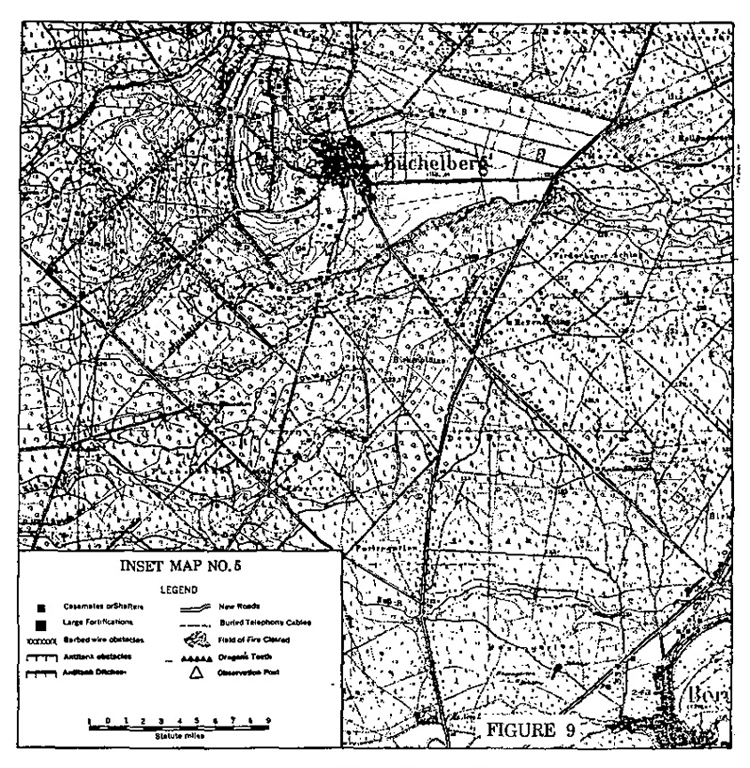

Accurate and detailed representations of the known fortifications in the areas indicated by rectangles on the large fortifications map (fig. 2, facing p. 142) are marked on five large-scale maps of parts of the West Wall (figs. 4, 6, 7, 8, 9). The nature and location of the defenses on the terrain are shown, but the direction of fire of the active works are unknown. A study of the maps will reveal excellent adaptation of the works to the terrain, great density of fortified works on weak ground, continuous lines of obstacles, and adequate and strongly defended communications.

Map. Figure 2.—Map of a sector of the West Wall.

Map. Figure 2.—Map of a sector of the West Wall.

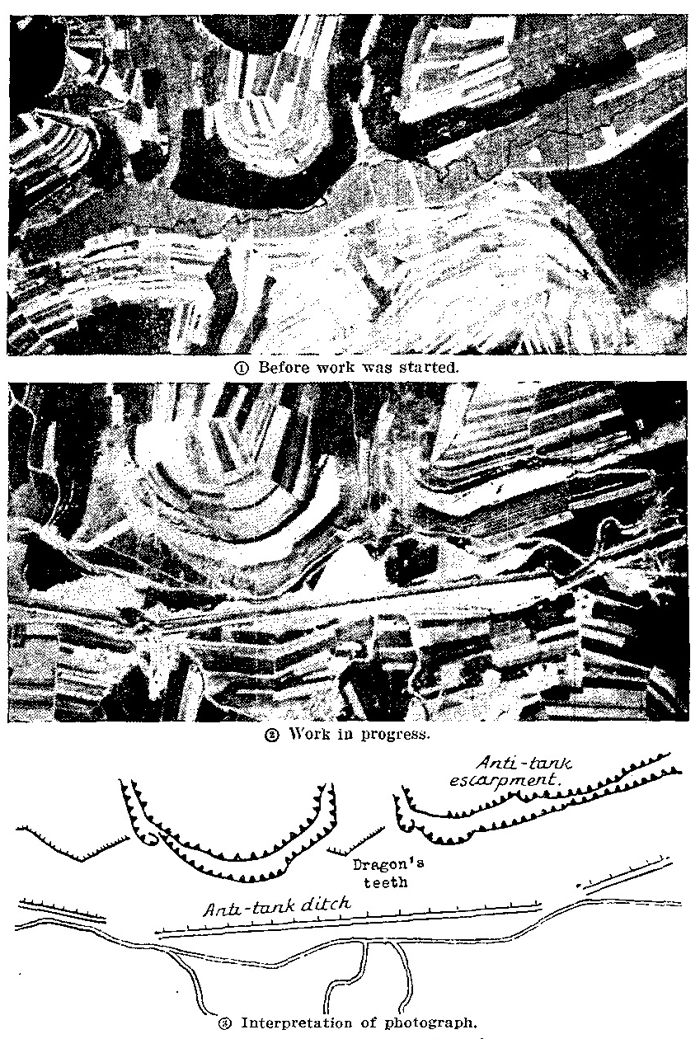

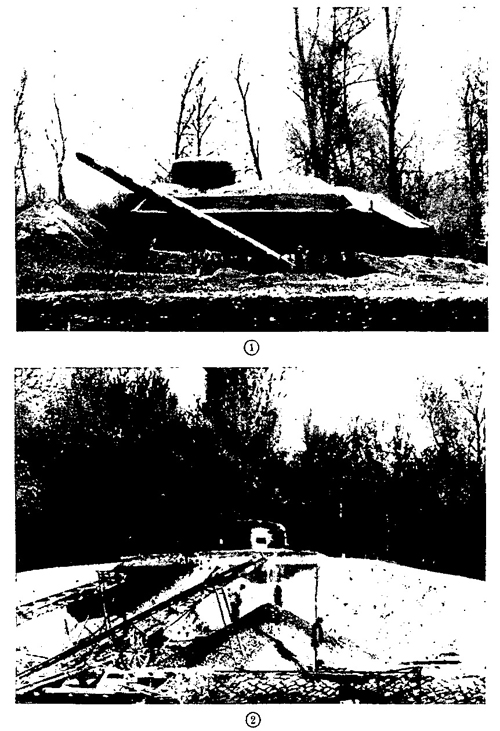

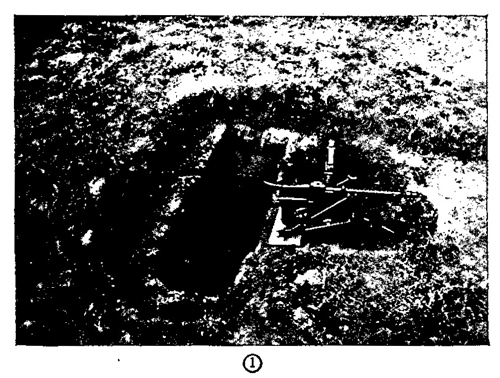

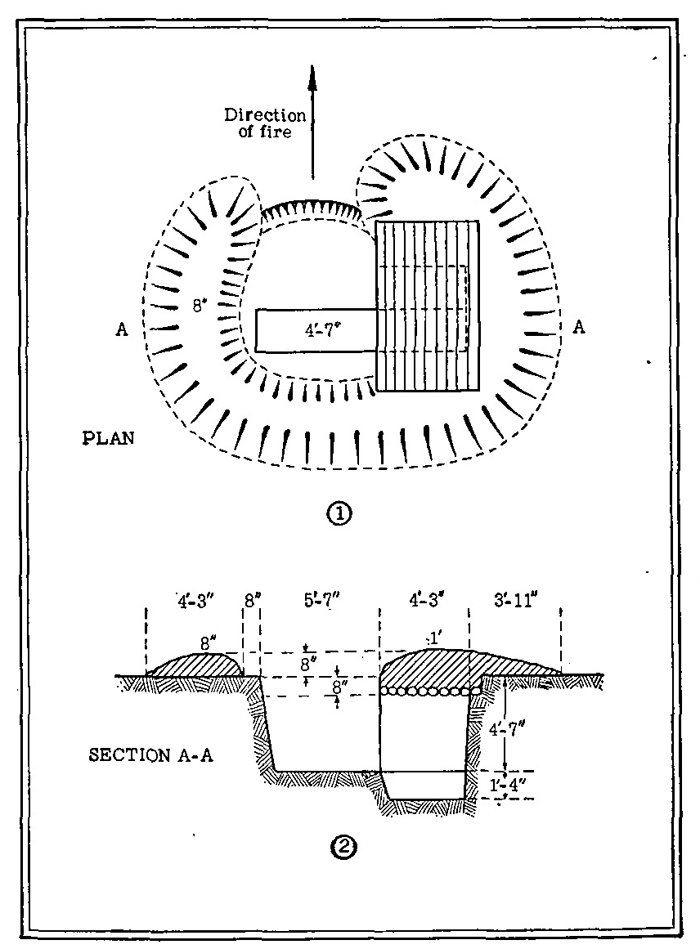

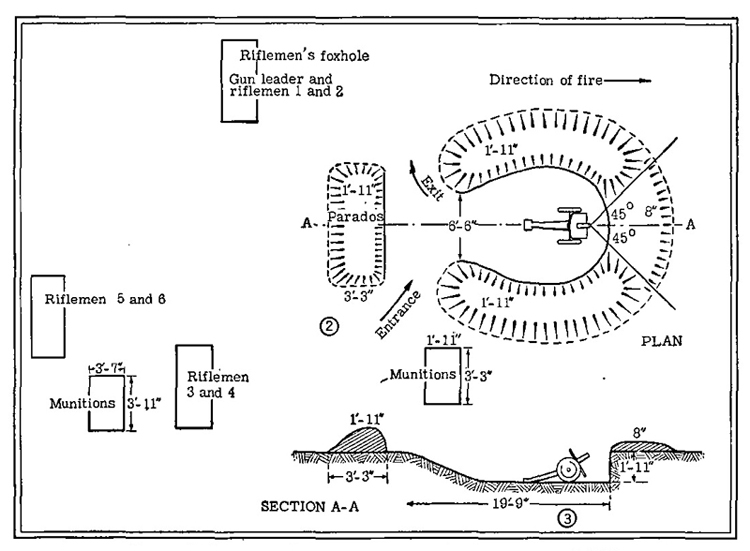

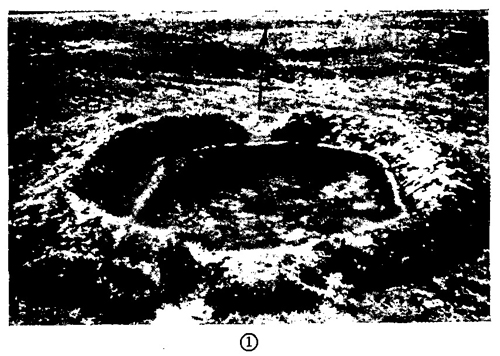

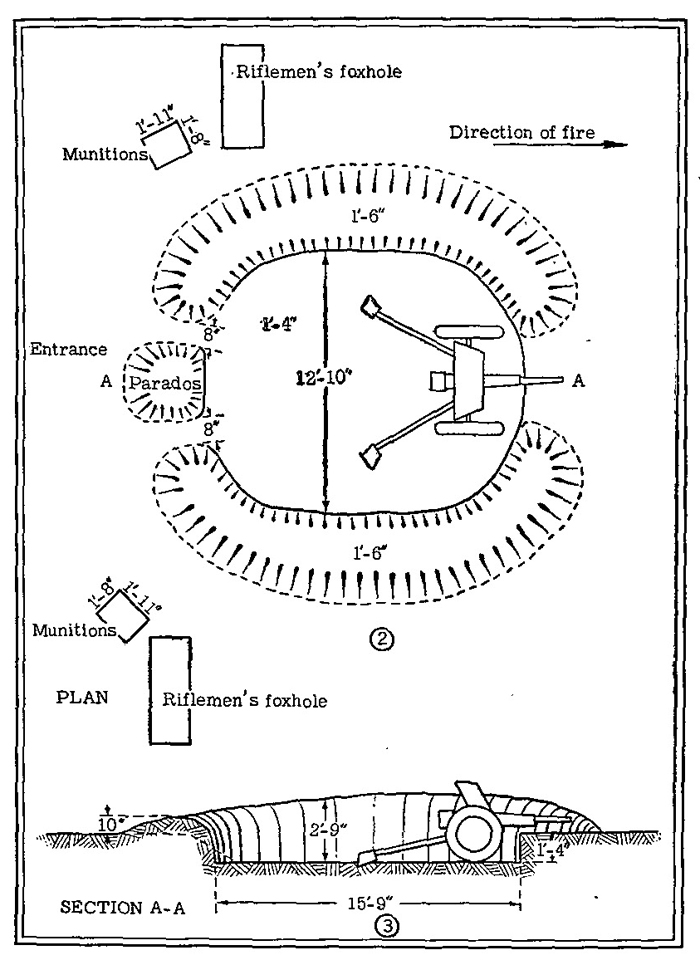

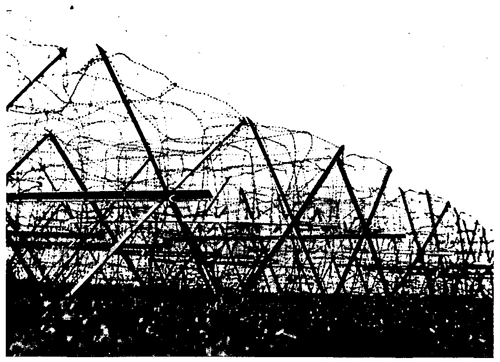

Actual aerial photographs of a part of the Otterbach sector of the West Wall are shown in figure 5 (1) and (2), and they match the terrain in the lower middle part of figure 4. An interpretive sketch of this area has been made in figure 5 (3).

The sector includes:

a. A continuous band of antitank obstacles.

b. Continuous bands of wire entanglements.

c. A deep area of fortified works, the fire from

which covers the obstacles and all the terrain.

d. Fortified shelters, without armament, for quartering troops.

e. Artillery emplacements.

The density of the fortified works in this sector is 28 forts in 700 yards of front, or 1 for every 25 yards. The average distance between works is 75 yards. It is not believed, however, that this is a typical section of the West Wall, but rather that this terrain, favoring attack, required defensive works very closely spaced. The depth of the installation is less than the 2,000- to 4,000-yard depth mentioned in paragraph 17b, above, and it is probable that only part of the zone is shown. On the other hand, the defense of the terrain at this point may have been made most effective by the close

spacing of the forts rather than by disposing them in greater depth. The Germans are not bound by copybook rules but always adapt their defenses to the terrain.

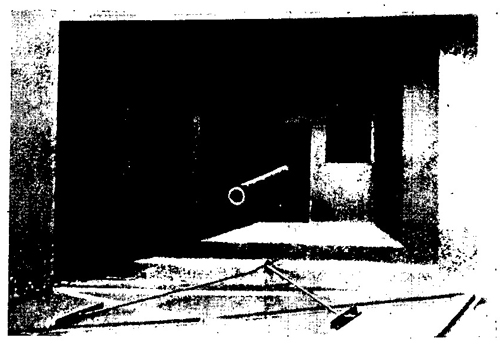

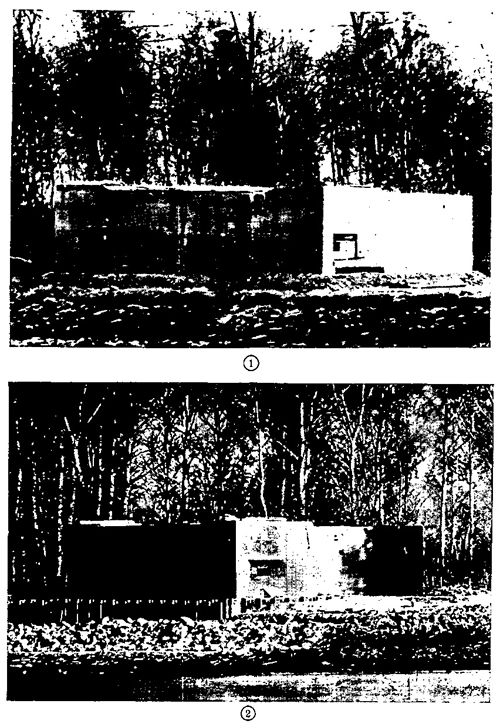

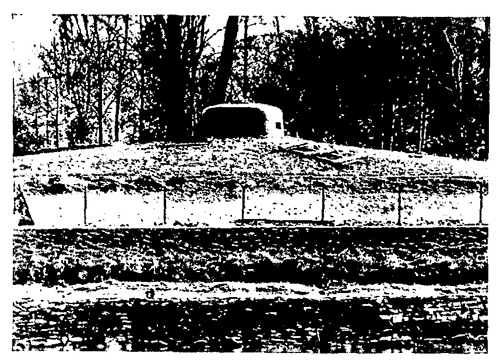

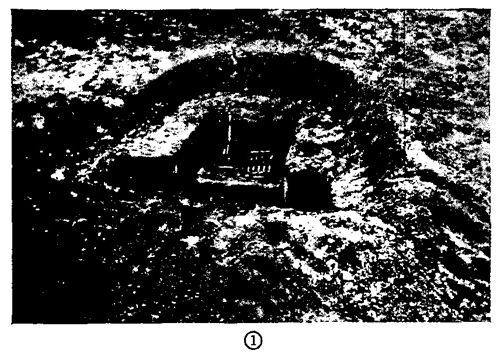

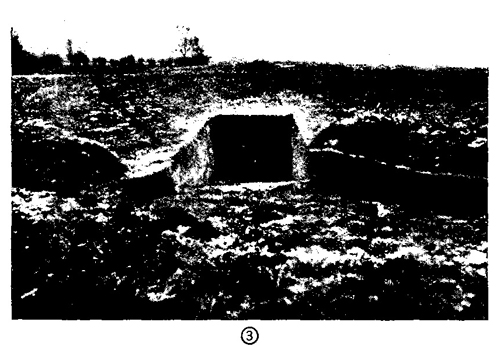

As one stands in front of the defenses, the fact that there are numerous forts is not visually apparent. (See fig. 10). The defenses are normally not so visible as those pictured in this illustration.)

Figure 4.—Plotted area No. 1 (Otterbach sector).

Figure 5.—Aerial photographs plotted in figure 4.

Figure 5 (continued).—Aerial photographs ploffed in figure 4.

Figure 6.—Plotted area No. 2,

Figure 7.—Plotted area No. 3.

Figure 8.—Plotted area No. 4.

Figure 9.—Plotted area No. 5.

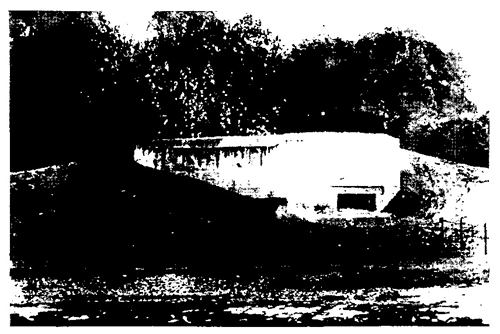

The concrete works have been earth-covered; the ground has been graded to provide grazing fire j and the completed installation has been so integrated into the topography as almost to escape notice. Thus an attacking force may not be able to spot defending centers of resistance readily, a fact which may encourage doubts and hesitation as to where to concentrate heavy, indirect artillery fire. Furthermore, bunkers are so widely separated that fire which misses one will not hit another.

Figure 10.—Works concealed in terrain.

19. PERMANENT FORTIFICATIONS

a. Types of Works

The "West Wall in general contains two kinds of fortified works: the decentralized type and the closed type. The decentralized type consists of a group of mutually supporting concrete bunkers or steel turrets united into a center of resistance that is capable of continuous machine-gun and antitank fire. In other words, a work of the decentralized type is characterized by firepower. The separate bunkers are often interconnected by tunnels to facilitate the relief of personnel, the supply of ammunition, and the care and removal of the wounded.

The term "closed type" is applied to strong underground shelters of concrete which have no emplacements for guns. These works have the important function of sheltering large bodies of infantry and reserves from air and artillery bombardment. At the proper time the waiting reserves are committed fresh from the shelters in a counterattack to drive back the enemy and to restore the position. The closed type of fortification is also used for relieving units and for the storage of ammunition. Lacking firepower, the shelters are protected by obstacles and field works. Whatever the differences in characteristics, both the decentralized type and the closed type have one important feature in common: they are intended to hold ground against the enemy's maximum effort. In the accomplishment of this mission, these permanent works are complemented by extensive field fortifications which add flexibility to the defense. The field works are

occupied during engagements by the troops who are sheltered in the closed type of fortifications. (German field fortifications are discussed in par. 24, below.)

b. Thickness of Concrete and Armor