Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

TACTICS & FIRE CONTROL OF RUSSIAN ARTILLERY IN ATTACK AND DEFENSE DURING 1941, 1942, and 1944 AND THEIR DEVELOPMENT IN RECENT TIMES BY OBERST (I.G) HANS-GEORG RICHERT

"The author of the study ... was regarded as an expert in the field of artillery. In his subsequent service as a divisional general stuff officer in the East he was able to further broaden his artillery experience and to add to it by learning from the judgement of his divisional commander, who had been active in the field service of the artillery in the East. Finally, when he assumed command of an infantry regiment... he observed with the trained eye of an artilleryman, the heavy battles in which he led his infantry regiment with great skill. As a result, he seemed particularly suited to write this study. The author has written his observations on Russian artillery tactics in five chapters. In these, a total of six engagements are described and the lessons to be learned from them have been indicated."

Introduction. Training manuals of the Russian Artillery in 1941

Up to the beginning of the war in 1941, the training of the Russian artillery was undoubtedly conducted on the basis of the "Field Service Regulation for the Red Army," published in 1936, which contained a number of items from the former German Army Manual No. 300 entitled "Operations," on the basis of the field manual, and of the firing manual of the Russian artillery. German translations of these three manuals, published by Mittler & Sohn or Offene Worte, Berlin, were sold on the German book market,

Even the very first engagements showed that these manuals, which were sound, had not yet been fully assimilated by the Russian artillery.

It is not known whether there were still other training directives or training instructions in the classified category in addition to the manuals mentioned.

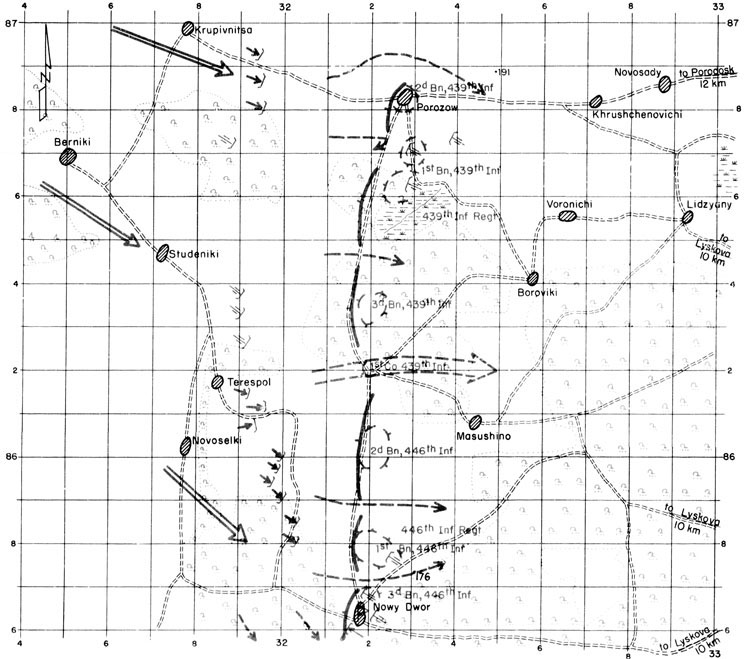

Example I. Russian Divisional Artillery in Mobile Warfare During the

Summer of 1941. The Engagement at Porozow and Nowy Dwor in June 1941

Map 1. The Engagement at Porosow and Nowy Dwor in June 1941. Northwestern corner of Kobrin Sheet, NN 35-10, scale 1 : 250,000

Organization of Divisional Artillery

In 1941, the table of organization for the divisional artillery of a Russian infantry division provided for three battalions of 76.2-mm guns and one battalion of 122-mm field howitzers. One artillery commander and one artillery regimental commander were to form the command staffs. According to information obtained from prisoners of war at that time, however, the artillery commander was lacking in many of the infantry divisions. In those divisions which had both an artillery commander and an artillery regimental commander, the former was directly in charge of the field howitzer battalion, while the latter was in charge of the three gun battalions. Probably in a majority of infantry divisions one man exercised both functions.

Situation

In June 1941, the beginning of the Eastern campaign brought on the dual battle of Bialystok and Minsk. As part of the pincer movement of von Kluge's army, the German 134th Infantry Division, advancing from the area northwest of Brest Litovsk, was given the mission of preventing an eastward or southeastward withdrawal of strong Russian forces east of the Bialowiez forest.

In a line from Porozow to Nowy Dwor, approximately fifteen kilometers long, six battalion groups of the division, supported by two light artillery battalions and one 100-mm gun battery, placed themselves astride the Russians path, moving directly from the march column, while' the mobile elements and the third regimental group lunged on in the direction of Lyskova-Porodosk-Izabellin under the command of the L Corps.

Terrain Estimate

The terrain in the Porozow-Terespol-Nowy Dwor area is rather irregular and, in

general, slopes from northwest to southeast, so that observation in open terrain

was easier for the Russians than for the Germans.

The division's approach route from the south toward Nowy Dwor was along a one-way

road, which over a distance of about eleven kilometers, led through a marsh. This

marsh was partly covered with shrubbery and was not passable for German troops at

the time, since the paths leading through it were known only to the inhabitants of

the region. Later the Russians used them, occasionally even with light farm carts.

The forest shown on the 1 : 250,000 - scale map was a typical Russian jungle and

the terrain represented as open was partly covered with shrubbery, so that the

Russian troops had excellent opportunities for approach. The villages wore

sprawling groups of farmers' huts, into which the Russians could easily infiltrate

at night, since the German security patrols were situated at great distances from

each another.

All roads were tracks through either wet marsh or deep sand. This allowed all horse-drawn troops to march almost without a sound, if appropriate orders were given and complete silence imposed.

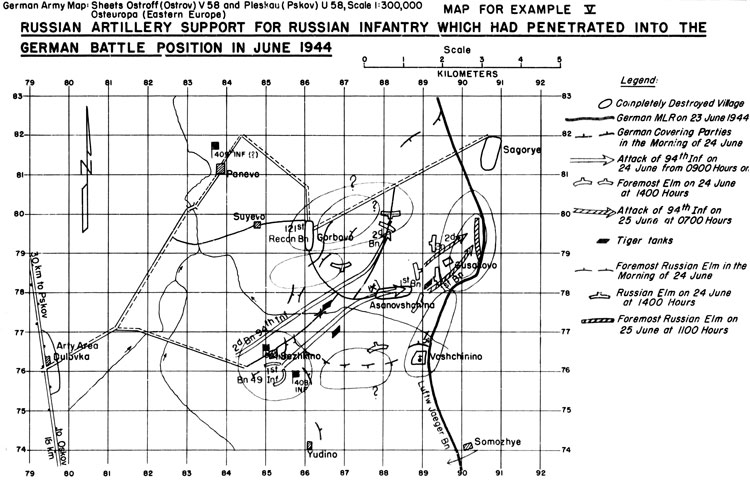

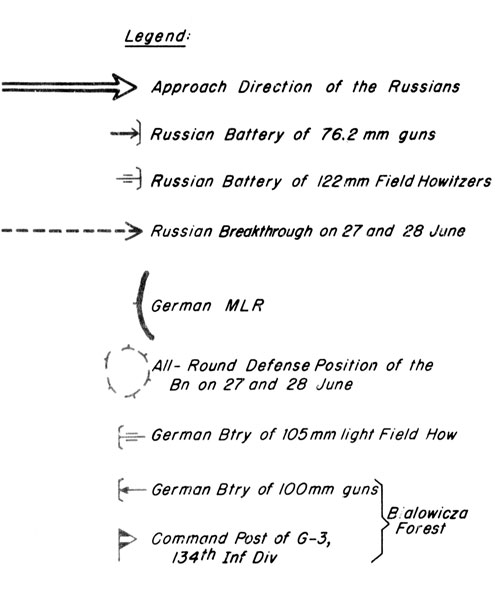

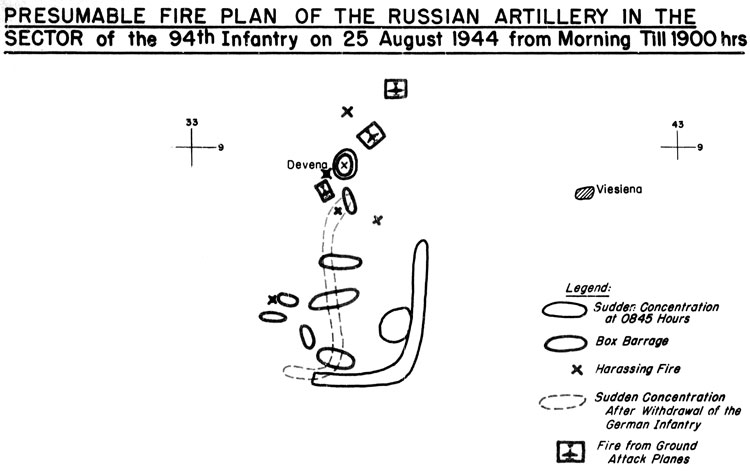

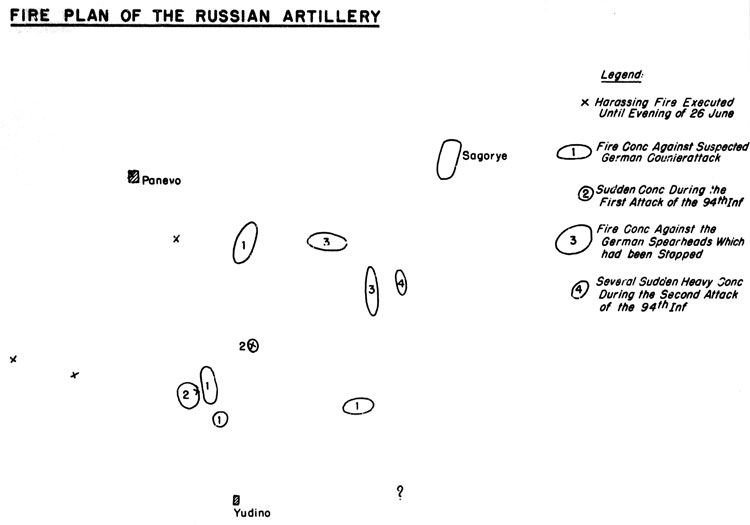

Summary of the Engagement and Conduct of the Russian Artillery

On the afternoon of 26 June, combat groups in battalion strength, which had escaped

detection by the German aerial reconnaissance, pushed southeastward from the large

forest area and for the first time attacked the videly dispersed 134tn Division,

This division was still marching with flank security, and the tail end of the

second regimental group had just passed through Nowy Dwor in the direction of

Lyskova. The attack, which had not been preceded by an artillery preparation and

which apparently was conducted from the march column, was repulsed. Throughout the

night of 26 June, fire was exchanged all along the front, which was still in the

process of being organized.

Late in the morning, light Russian artillery suddenly joined the battle very

effectively with observed fire from battery after battery. Every battery moved

speedily into firing position upon arrival and opened fire; ad a result, it was

possible to estimate approximately the number of batteries firing. It was very

difficult, however, to identify the extremely well-concealed observation posts,

whereas a few poorly defiladed firing positions were easily located from the muzzle

flashes of tho weapons. The Russian battery commanders, based on keen observation,

combated every Gorman movement and every machine gun they had identified in an

exposed firing position by means of a flawless bracketing method passing over into

ladder fire. This meticulously accurate artillery fire caused great losses among

the German troops and had a damaging morale effect on them.

On the afternoon of 27 June, 122-mm field howitzers also joined in the battle from the area around Terespol. Immediately afterward, Russian infantry attacked all along the front in several waves in an effort to force a breakthrough and to bring about a decision. In this attack, several Russian artillery observers along with wire sections which were stringing wire abreast of the attackers were clearly identified in the leading waves of the infantry. Whether still more artillery observers were advancing in the following waves of this typical Russian infantry attack remained unknown, but it appeared likely. The use of wiro sections in the leading wave of attack shows clearly that the Russian divisional artillery had no radio telephones at that time.

During this engagement there was no attempt to concentrate the fire of more than one battery, let alone that of several battalions. In all cases, batteries adjusted by the bracketing method, and even though, in some instances, they fired at two adjacent targets, their fire was not synchronized.

The amount of ammunition employed in this fighting fluctuated greatly and gradually decreased on the evening of 27 June, As it grew darker, the artillery fire ceased; the nocturnal harassing fire which the Germans had anticipated, at least against the villages they were occupying, did not come. Neither were the concealed positions of the German artillery taken under systematic fire; only a few projectiles fell in the vicinity of the positions, apparently because the Russian divisional artillery had no sound-ranging instruments at that time.

The numerical superiority of the Russian artillery, the good support which it furnished the Russian infantry by well-observed and well-adjusted fire, and the shortage of ammunition which developed among the German troops, whose supply route, eleven kilometers of which ran through the marsh south of Nowy Dwor, had been blocked by Russian forces, all combined to produce a Russian breakthrough. They did, however, sustain heavy losses at the boundary line between the two infantry regiments and between the battalions, which at night had established perimeter defense positions. The troops in the two villages of Porozow; and Nowy Dwor, on the other hand, were able to hold their ground until the morning of 28 June by engaging in bitter close combat which even extended to the interior of the villages and to the division command post located in Nowy Dwor.

During the night, the Russians poured southeastward and eastward through the gaps

mentioned above and took along their entire artillery, which, being horse-driven,

was able to move almost without a sound. As they did so, the Russians completely

encircled the various German combat groups, some of which held their ground as long

as they could and then fought their way out with their last rounds of ammunition

(elements of the 2d and 3d Battalions, 439th Infantry, even fought with their

bayonets!) and broke through eastward in the direction of the corps command post at

Lyskova.

In the confusion caused by this German effort to break out, the Russian artillery

did not fire a single round, but whether this was due to a lack of ammunition is

uncertain. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that the Russian divisional

artillery had a decisive share in the success of the Russian units when they broke

out of the pocket and the Bialowicz Forest. On the basis of the observations made

and a number of estimates, which are nearly all in agreement, as well as the

exploration of the battle field undertaken a few days later, at least two

battalions of 76.2~mm guns and one to two batteries of 122-mm field howitzers were

employed in the Porozow area. At least one battalion of 76.2-mm guns and one of

122-mm field howitzers supported the Russian attack from the Terospol area, aiming

primarily at the boundary between the two German infantry regiments. At least two

battalions of 76.2-mm guns had joined in the battle in the Nowy Dwor area, one

battery at a time, using large amounts of ammunition. It is accordingly probable

that two divisions participated in the battle on the Russian side.

From the point of view of the artillery, this engagement may be summarized as follows:

1) The divisional artillery fought in very close cooperation with the infantry.

2) The battery was the largest unit allowed to fire at one target.

3) Observation was well organized and apparently functioned very accurately, as was

later confirmed again and again.

4) The observation posts wore extremely well camouflaged.

5) Adjustment fire on the various targets was accurate. The fire for effect was

well aimed, although the time needed for it varied.

6) The volume of the fire varied; toward evening it decreased more and more.

...

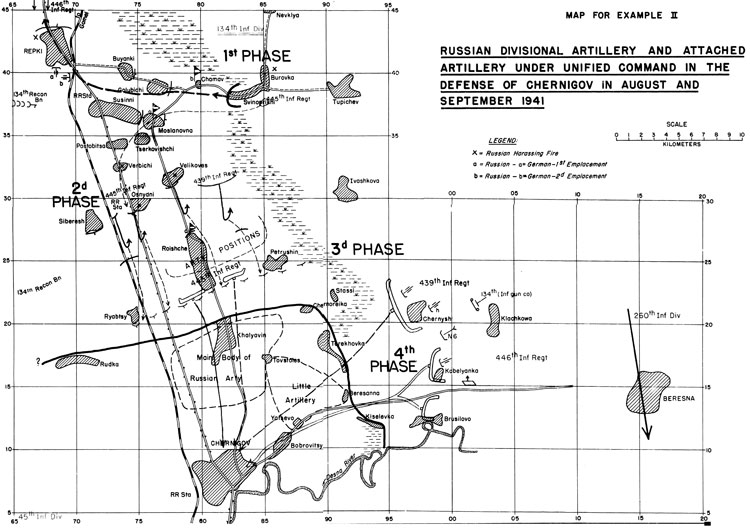

Example II. Russian Divisional and Attached Artillery Under Unified Command in the Defense of

Chernigov in August and September 1941

Map 2. Russian Divisional Artillery and Attached Artillery under Unified Command in the Defense Of Chernigov in August and September 1941. German Map, Sheet W52, Chernigov, scale 1 : 300,000; U.S. Map, Nezhin sheet, M. 36 - 1, scale 1 : 250,000

Strategic Situation

At the end of August 1941, to repulse the attack which the Germans had undertaken

from the Gomel area and east thereof against the northern flank of the Russian

forces fighting in the area on both sides of Kiev, the Russian command formed a

strong defensive flank, utilizing the Desna River sector, the terrain of which was

very suitable for the purpose. In this operation it was the mission of the

Chernigov bridgehead, which was provided with heavy field-type fortifications, to

furnish supplies to, and subsequently absorb those Russian elements which were

fighting a delaying action north and northwest of the Desna River. Chernigov was

defended by fiercely fighting units, which were particularly well equipped with

artillery of all types; their supply service was substantially facilitated by the

presence of a peacetime Army ammunition dump in Chernigov.

The German 45th Infantry Division, coming from the west from the vicinity of

Ovruch, had the mission of forcing a crossing of the Desna River southwest of

Chernigov. The mission of the 134th Infantry Division, coming from Gomel, was to

take Chernigov and cross the Desna south of this town. The 260th Infantry Division,

hurrying to the scene aftar fighting heavy battles in Rogachev, was to be committed

toward Neshin by way of Berezina and was to accomplish a crossing of the Desna river

approximately thirty kilometers east of Chernigov.

Tactical Situation

North of the Chernigov bridgehead heavy Russian forces, including cavalry reinforced by a few light tanks, delayed the advance of the 134th Infantry Division by a well-conducted defensive action, In the course of this action heavy fighting took place at the narrow stretch of firm ground north, of Ropki, which was flanked by marshes on both sides. In order to continue fighting and to attack Chernigov a passage had to be won through this narrow stretch of terrain, which was of particular importance to the movement of supplies for tho division, since it had its supply base in Gomel. To speed up the battle, division headquarters decided after studying the maps to move its units as follows: The 439th and 445th Regimentsgruppen* - (reinforced), the heavy artillery battalion, the antitank units, and the attached GHQ troops were to lunge around the marsh on the east by way of Aleksandrovka-Nevklya-Burovka. This movement had been cleared with the 260th Division, whose right line of advance ran along a section of this route. The 446th Regimentsgruppe, on the other hand, was to tie down the Russian forces north of Repki, and the 134th Reconnaissance Battalion, which had been reinforced by motorized engineers and antitank elements, was to strike through Radul, situated on the eastern bank of the Dnieper River, advance from the west in the direction of Golubichi, and engage in reconnaissance.

[* - A Regimentsgruppe is a reinforced battalion which has been given a regimental designation.]

Nothing was known about the enemy situation south of the marshes. The weak German aerial reconnaissance forces had yielded no noteworthy results. The condition of the 134th Division gave some cause for concern, since the combat strengths of the infantry were about seventy percent of the strengths provided for by the table of organization and the horse teams of the horse-drawn units had already become so weak that they reduced the rate of march. Ammunition and fuel stocks, on the other hand, were full and the flow of food from the countryside was insured. Russian aircraft of the Rata type attacked the marching elements of the division several times, while German lighter protection was scarcely worth mentioning.

Terrain Description

Except for the Gomel-Chernigov highway, all roads were either covered by deep layers of dust or were marshy, which substantially reduced the rate of march.

As a result of the August heat, the marshes east of Repki had become passable in part for infantry with field-stripped weapons and for Russian farm carts.

The open terrain undulated slightly here and there and afforded unusually good opportunities for observation for the artillery and heavy canons of both sides. In part, the range of observation even exceeded the range of fire.

The forests were typically Russian, containing trees of various sorts, approximately fifty to sixty years old, and also thick underbrush.

Summary of the Attack

The attack on Chernigov proceeded in four phases.

First Phase: Opening a Passage Through the Repki Bottleneck

At 1400 hours on the day of attack (28 or 29 August), after a brief assembly, the reinforced 439th Infantry Regiment attacked on both sides of the western part of Burovka, its forces being echeloned in great depth. When darkness fell, it had gained the northern edge of Repki against increasingly stiff resistance and, at the Repki brickyard, had established contact with the 446th Infantry Regiment, which was doggedly fighting its way forward from the north. On the other hand, the 445th Infantry Regiment, echeloned in depth to the left followed the 439th Infantry Regiment, broke the Russian resistance which continued to flare up and intercepted minor Russian thrusts into the southern flank of the 439th Infantry Regiment which was fighting to its right and front.

The reinforced 134th Reconnaissance Battalion did not reach the vicinity of Golubichi until the next morning.

Favored by a light cast wind, a light smoke battalion (105-mm) assigned to the division screened the area near the flank and the flank of the attacking 439th Infantry Regiment from the observed Russian artillery fire which was to be expected.

In these engagements, it was only light Russian artillery for the time being that went into action, with observed fire against the 446th Infantry Regiment, located in the Repki area, and against the reconnaissance battalion located farther to the west. Fire from medium artillery, on the other hand, as unobserved harassing fire, failed to delay materially the attack of the 439th Infantry Regiment. It was only toward evening that the Russian artillery shifted its fire from Repki to the 439th Infantry Regiment. Now the Russians observed their fire, and it was well adjusted and very flexible. But the impetus of the Gorman 439th Infantry Regiment was undi- minished by it, even though the Mercian artillery was able to help only with observed fire and though the heavy artillery was unable to go into action much before evening owing to difficulties which it had encountered on the march. The observation battalion assigned to the division had not yet arrived from Gomel and, therefore, was unable to identify the defiladed Russian positions. Aircraft was not available.

The 445th Infantry Regiment, which during the attack had turned off at Moslakovka

in the direction of Verbichi, came too late in its effort to push forward from the

vicinity of Repki and cut off the Russian artillery, which very skillfully retired

in time in the direction of Chernigov.

The failure of the Russian artillery to repulse the attack of the 134th Infantry

Division on that day or at least to delay it decisively apparently was due to the

fact that the artillery had been split up and assigned to infantry combat groups.

The losses which this artillery fire caused to the 439th and 445th Infantry

Regiments proved not too severe until the close fighting for Repki; the losses

sustained by the 446th Infantry Regiment were a little higher. The objectives

assigned for the attack were achieved by all elements with the exception of the

reinforced reconnaissance battalion, which although it sustained high losses, was

unable to make progress against the Russian infantry, which was provided with

numerous antitank guns, mortars, and light artillery.

During the following night the Russian artillery, using 70-, 100-, and 122-mm guns, for the first time directed systematic, far-reaching, and well-adjusted harassing fire at Moslakovka in which the advance echelon of the divisional staff, which had already moved there, was caught; and also hit Burovka, Golubichi, and Repki, giving the Germans cause for considerable concern. At about the same time, light Russian artillery directed harassing fire at elements of the 445th Infantry Regiment at Osnyaki, Verbichi, and Velikoves. It was clear to see that this harassing fire was under unified control.

Second Phase of the Attack: Shortened Attack Methods

Because the division was under great pressure by higher headquarters, it decided to attack Chernigov by a shortened method, with concentrated forces moving along both sides of the highway. To this end, the 445th Infantry Regiment began to move forward on both sides of the highway across a line running from the Siberesh railroad station to Osnyaki, while the 439th Infantry Regiment, situated east of the 445th Infantry, was to undertake an attack in the direction of Khalyavin, with its left flank advancing alone the marshes by way of Petrushin. This attack was supported by all four divisional artillery battalions and two battalions of GHQ artillery under the command of a GHQ artillery command staff.

Soon after the regiments had begun to move, the attack was stopped by heavy artillery fire from a large number of batteries. This fire assumed proportions which had never before been experienced, and inflicted severe losses on the Germans, Artillery reconnaissance, which went to work immediately with sound and flash ranging instruments, captive balloons, and aircraft, identified approximately forty firing batteries with calibers ranging from 76.2 to 220-mm. This reconnaissance data had been checked and rechecked and hence admitted of no doubt.

With virtually inexhaustible stocks of ammunition the Russian artillery fired at any German movement, however insignificant, and even at single German vehicles. It did this not only with individual batteries, as it had been in the habit of doing previously, but in most cases with several batteries, apparently at battalion level. Every German attack which was identified was hit by the combined fire of a great number of batteries. Nevertheless, the German infantry, with the concentrated support of whatever heavy weapons were available, undertook a rapid succession of attacks with limited objectives at a variety of points and advanced to the Ryabtsy -southern edge of Roishche-Petrushin line. It was only on the third day of attack, after the division had suffered a total loss cf eight hundred dead and wounded among its infantrymen, almost entirely as the result of the Russian artillery fire, that the division received the permission, which it had urgently requested several times, to discontinue this type of attack.

The artillery of the division, which had been reinforced by an active observation (sound-and-flash) battalion with balloon platoon, two platoons of heavy GHQ artillery, and, later on, a howitzer battery, had, under the command of an artillery commander, opened systematic fire on the Russian artillery as soon as the first artillery reconnaissance results were available. Unfortunately, the captive balloon became the special target of the Russian Rata planes during daytime and was soon incapacitated, since German fighter protection was almost never available and the 20-mm anti-aircraft artillery was not sufficiently effective. Particularly during the night, but also by day, Russian 76,2-, 107-, 122-, and 150-mn cannon laid systematic long-range harassing fire on various points of the road from Gomel and at almost all villages up to the Durovka-Repki line. In this harassing fire the Russians changed their targets and their rate of fire at short intervals. They even hit the German's main medical dressing station, which at that time was still clearly marked in the manner prescribed by the Geneva Convention and hence must have been identified by Russian aerial reconnaissance.

The systematic bombardment of all German command posts from the regiment on up made it appear likely that the Russians were, for the first, time, using radio direction finding equipment and were immediately making available to its artillery units the data thus obtained. This seemed logical inasmuch as the Germans were maintaining radio communications between division operations officers and corps headquarters, employing for this purpose portable radio teams equipped with 5-watt, 3120-950 kilocycle sets and other teams equipped with 100-watt, 1200-200 kilocycle sets*.

[* - In the original the author indicated use of "Kleinfunktrupps a und b," and "mittlorer Funktrupp b," respectively, referring to the 5- and 100-watt radio sets. It is not clear whether the lettered designations refer to the radio sets (or sections) or to the types of sets used. Since it is not pertinent to the general context, and since mention of the use of radio communications is sufficient, without going into detail, to establish the means by which the Russians presumably located and fired on the command posts, no attempt has been ready to clear up this obscure point.]

In addition, the Russians placed accurate artillery fire first on heavy German

batteries and later on a few light batteries, adjusting the fire by using aerial

observation by day and sound ranging equipment by day and night. It was impossible

to establish with certainty in subsequent interrogations of prisoners of war

whether the Russians were, at that time, using battalions and batteries when and as

needed for their artillery missions or whether they had possibly organized several

long- and short-ranging combat groups. In view of the lack o£ flexibility of

Asiatic-Russian thinking, however, the former possibility seemed more likely.

Third Phase of Attack: Artillery Battle and Regrouping of 134th Division

While the Germans systematically continued to shell the Russian artillery to the extent that their ammunition stocks permitted, the division regrouped its forces* (Because of transportation difficulties existing between Gomel and the front it was impossibly to move up sufficient quantities of ammunition, especially for heavy artillery.)

The 446th Infantry Regiment, up to then held in reserve behind the point of main effort formed by the 445th Infantry, was dispatched to the left flank. The 446th Infantry reached the area north of Kobelyanka-Brusilovo-Klachkova by way of Ivashkova and, together with an assault gun battalion assembled there for an attack. It was protected against observation from south and west. The Russians identified only the advanced security details in this assembly; they were unaware of its depth, its significance, and the effect it was to have.

The 439th Infantry assembled around the northwest of Chernyshi, while the 445th Infantry remained on the line it had reached.

The 134th Reconnaissance Battalion provided security, tied the Russians down by

lively patrol activity northwest of Chernigov, and established contact with the

northern flank of the 45th Division. For a regrouping of the artillery, the

following points had to be considered:

1) It was necessary to continue the bombardment of the Russian artillery without

interruption.

2) It was necessary to insure that movement of batteries which had already been engaged in the fire fight would not reveal to the enemy reconnaissance the shift of the point of main effort of the division.

3) It was necessary to insure that the artillery was ready to give its support to the attacking infantry on the day of attack at the very latest.

Because of these factors the majority of the batteries remained in the firing positions around Roishche, the decision to keep them there being also prompted by the consideration that the condition of the Gomel-Chernigov road in the present muddy season would impede the movement of ammunition. The moving infantry regiments were followed for the time being only by stronger advance detachment of their organic artillery battalions with the base pieces coming later, especially as the German batteries at that time still had four guns each. The smoke-shell battalion, which was hardly of any use in an artillery battle because at that time it had only a range of barely three kilometers, was the solo unit to change its position immediately. It moved into position on both sides of the new boundary line between the 439th and 446th Infantry Regiments and covered the movement of the infantry regiments into their new positions. Another unit following the 446th Infantry Regiment was the assault gun battalion assigned to the division Use of this battalion in the artillery battle had been prohibited in order to save materiel.

During the next to the last night preceding the final day of attack (8 September) the advance detachments of a heavy motorized GHQ artillery battalion was moved up to prepare the employment of its three batteries in the Chernyshi area. During the night of 7 September, the night before the attack, the shift of the six light batteries of the organic battalion and the GHQ artillery battalion was accomplished so that by the morning of the day of attack (8 September) the regrouping movement had been completed and everything was ready for action. Roving guns of the ten batteries which had remained in the area around Roishche (three light field howitzer batteries, five heavy field howitzer batteries, one 100-mm gun battery, one howitzer battery) moved into the nine firing positions which hid been abandoned in that area. The 134th Engineer Battalion was assigned to the infantry regiments on the basis of one of its companies to each regiment, to be employed as engineer combat patrols with or without flamethrowers.

The 134th Panzer Jager Battalion was assembled in the rear of the 439th and 446th Infantry Regiments to be employed platoon by platoon to fire at the embrasures of bunkers.

The remarkable thing was that the Russian artillery had scarcely taken any notice of the extensive movements necessary for this regrouping, part of which had been undertaken during daytime, and, evidently failing to grasp their significance, had fired only a few shells at them.

Whether the Russian artillery had been prevented from taking them under a more effective fire by the extremely vigorous, systematic bombardment undertaken by the German artillery, while the German heavy infantry weapons primarily shelled observation posts which had been identified or were suspected, is anybody's guess. In any case, there was no regrouping of Russian artillery on a large scale, and the northerly direction remained its chief direction of observation and fire.

Because of the severe losses which the division had suffered in the abortive second phase of the attack on Chernigov, aine squadrons of twin-engine He-111 bombers from the Hindenburg Bombardment Wing were assigned to support the division in its decisive penetration into the Russian battle position beyond the Russian main line of resistance, which ran from Kiselevka by way of Terekhovka, Chernoreika and the northern edge of Khalyavin to Rudka. The squadrons were first employed on the morning of 8 September in close cooperation with the reinforced artillery of the 134th Division to combat the enemy batteries that, according to available reconnaissance results had not already been neutralized. To this end, the German artillery identified the various Russian batteries by means of equal numbers of smfifce shells and delayed-action fuze shells according to a carefully planned and previously discussed and adopted plan of fire. Cooperation between the artillery and the various squadrons of the bombardment wing was excellent. After the whole fire plan had been carried out and 250- and 500 kilogram demolition bombs had been dropped, the Russian artillery was silent.

Shortly before sunset the entire wing, this time flying at an altitude of less than a hundred meters, dropped light, heavy, and superheavy bombs at the points where the infantry was to achieve penetrations. The lateral limits of these points were indicated by heavy infantry weapons and a few light batteries, which, using smoke and high-explosive ammunition, directed an echeloned volley fire at one gun at a time. In the meantime the main body of the artillery was to hold the Russian artillery at bay, which, partly from previously unknown alternate positions, was still engaging in well-adjusted harassing fire, despite the heavy damage inflicted on it by the German artillery arid aircraft in the morning. The combat patrols of the German infantry and engineers kept so close to the exploding aerial bombs that bomb fragments flew past their ears on a number of occasions. The penetration was achieved without too many losses; after darkness had fallen, the infantry combat groups broke into the forward artillery positions.

After penetration into the main Russian battle position, however, the fire control of the Russian artillery, which up to then had been faultless, ceased. One light battery located south of Khilyavin, which fired up to the last moment, was still stormed in daylight by elements of the 445th Infantry Regiment; the crew, which offered stubborn resistance, was killed to the last man. Utilizing the confusion which had now developed among the Russian, troops, a few German combat groups continued to fight their way forward during the night in the direction of Chernigov. The German artillery, accordingly, was allowed to direct unobserved fire only at and beyond Chernigov and was Obliged1 to either use ground observers in the leading ranks of the infantry or flawlessly functioning sound-ranging equipment for any fire which it directed at the area between the edge of Chernigov and its positions.

In the early morning of 9 September the advance elements of the German infantry, coming first from the east, then from the north-east, and still later from the north, forced their way into the ruins of Chernigov. A number of Russian batteries, altogether about thirty-five guns, were captured by the 45th Division directly southwest of Chernigov, because they had been unable to escape across the Desna River bridge. Most of the guns lay destroyed in their positions, the dead crews at their sides.

Critique of the Control and Employment of Artillery by the Russians at Chernigov

On the basis of the data obtained by artillery reconnaissance, numerous interrogations of prisoners of war, and the final inspection of the field of combat on 10 September, it was established that at least the following Russian units were employed in the Chernigov bridgehead under the command of a high Russian artillery general, whose name has unfortunately slipped the author's mind:

The divisional artillery of two infantry divisions;

Two regiments of the corps headquarters artillery as organized at that time;

One regiment of heavy GHQ artillery.

In addition to the field equipment of these batteries, the entire peacetime

ammunition dump at Chernigov was available. This explains the virtually

inconceivable quantities of ammunition used by the Russian artillery, which the

German observation battalion at the time conservatively estimated to have greatly

exceeded one hundred thousand rounds during the second, third, and fourth phases of

the attack.

It is undoubtedly to the credit of the Russian artillery that the defenders of

Chernigov were able to continue so long to offer stubborn resistance to the German

attack.

Even before the German attack began, the main body of the Russian artillery had moved into deeply-echeloned positions on both sides and south of Khalyavin and was ready for action in anticipation of the German attack along the Gomel-Chernigov highway. The defenses were very well prepared from the point of view of control, ballistics, communications, surveying, and ammunition supply.

In the Beresanka-Tovstoles-Yatsevo area there was only little artillery, while south of the Chernigov-Berezna road there was not a single battery. The Russian artillery had three different methods of combating the preparations for attack undertaken by the German infantry and artillery. Initially, it engaged in an occasionally "sadistic" harassing fire, from 76.2-, 107-, 122-, and 152-mm guns. Secondly, it engaged in a simple battery fire, which sometimes manifested itself as a steady fire for effect; here the crews conscientiously applied the bracketing method, checked the results and then maintained steady fire by groups. Thirdly, large numbers of Russian batteries of all calibers up to 155 millimeters conducted surprise fire attacks, which were not preceded by any conspicuous adjustment fire; in these instances, large quantities of ammunition were used and the rate of fire was very high, so that it was impossible to ascertain the amount of ammunition used by each gun.

The barrage which the Russian artillery fired in front of the Russian main line of resistance in the second phase of attack, and which came down in front of the 439th and 445th Infantry Regiments, was formidable, very flexible, and started with surprising promptness. It lasted until the German infantry achieved its final penetration (the area in front of the 445th Infantry was also hit by barrage fire in the fourth phase). For this barrage fire the Russians, in addition to excellent observers and the use of light signals, must have had very good technical means of communications and a dense, well-functioning telephone network. It is probable that they already had radiotelephone communications. After the Germans had penetrated into the depth of the Russian battle position, the sudden opening of fire in front of those sections of the Russian main line of resistance which were still intact stopped and the barrage fire was no longer feasible. During the fighting in the Russian battle position there was no longer any question of close fire control on the part of the Russian artillery.

In the artillery battle, well-concealed German firing positions were initially shelled by day and by night with the aid of aerial observation and sound-ranging. The planes, protected by fighters, remained behind the Russian main line of resistance. Several positions were hit and numerous losses inflicted on the German crews. Contrary to expectations, no artillery observers, left behind by the Russians in front of their main line of resistance, were found and caught.

During the first phase of the attack, 76.2-mm gun batteries were employed in an extremely flexible manner in the area of the Russian forward positions, particularly at Repki, and later on in the area of the Russian combat outposts in front of the 445th and 439th Infantry Regiments. These batteries fired a great amount of ammunition at every movement they identified and only at the last moment did they change their position very swiftly by means of horse teams, usually consisting of four spans, which they had kept close by. The success of the German attack with relatively few losses in the first phase must probably be attributed primarily to the double envelopment, which came as a tactical surprise to the Russians, and to the elimination of the Russian artillery observation from the south by means of a number of smoke screens laid close to one another. In addition, there was no unified artillery and fire control during this phase; apparently the various batteries were assigned to the infantry and the mobile elements.

During the second phase of the attack the German thrust was thwarted by the excellent command and fire control of the Russian artillery, which greatly outnumbered the Germans, occupied well-prepared firing positions, and was ready for action sooner than the Germans, During this phase, unfortunately, the Russian artillery also managed twice, by means of massive concentrations of surprise fire, in which numerous batteries participated, to smash German infantry in the process of assembling even before it could get its planned attack under way. The shock to the morale of the infantry was considerable.

During the third phase Russian reconnaissance failed to discern the grave significance of the regrouping of the 134th Division for the battle at Chernigov. As a result, the Russian artillery was scarcely able to disturb this regrouping, let alone shell it systematically, especially since the German artillery was not given permission to open fire until the very day of attack. The old artillery axiom that "firing is always a tactical action" was once again demonstrated beyond doubt. Since the significant German regrouping had not been identified, the Russian artillery continued to regard its chief targets as lying in a general northerly direction.

The attack of the Hindenburg Bombardment Wing against the Russian artillery was conducted from out of the sun and hence gave the Russian artillery command no hint of the coming German infantry attacks. It was only from the low-level raid of the Hindenburg Bombardment Wing shortly before sunset, when the planes flew in the direction to be taken by the attacking infantry, that the Russians were able to suspect what the immediate future held in store for them. But at that time it was too late to regroup their forces even on the smallest scale.

During the fourth phase, the Russian barrage in front of the 445th Infantry was very well executed. In front of the 439th Infantry Regiment it was still passably executed, while, to the complete surprise of all concerned, the 446th Infantry Regiment together with the assault guns assigned to it encountered no defensive artillery fire whatever and overran the Russian security parties and Russian infantry reserves subsequently hurried to the scene. After the Germans had penetrated into the Russian battle position, the Russian artillery command was no longer able to cope with the situation. Unified fire control ceased. Only a few batteries continued to fire, apparently of their own accord. Whatever elements had survived the fire of the German artillery and the bombers moved their guns off in the dark of night.

The conduct of the Russian artillery during the third and fourth phases shows clearly that the Russian artillery command and fire control, in spite of the very praiseworthy performance in the battle for Chernigov, was not yet equal to the flexible German combined-arms tactics, which at that time were still unhampered by the interference of the top-level command. It must be admitted, on the other hand, that Russian tactics at Chernigov attested to an unmistakable improvement over Russian tactics and fire control observed in June and July and as late as August 1941.

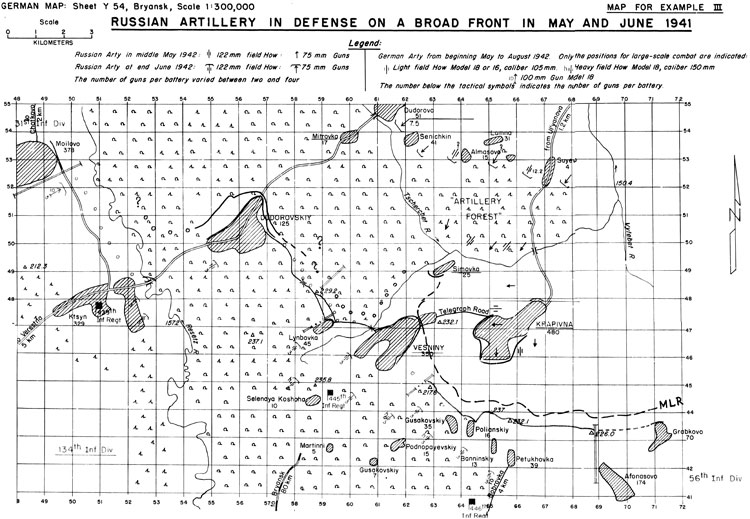

Example III. Russian Artillery Supporting Defensive Operations on a Broad Front

Map 3. Russian Artillery in Defense on a Broad Front in May and June 1941. German Map: Sheet Y 54, Bryansk, scale 1 : 300,000

Strategic Situation

The large-scale defensive battle in the area reaching from north and northwest of Orel to northeast of Bryansk had drawn to a close at the end of March 1942, after immense losses of men had been inflicted on the Russians before the German defensive front, which, although it had been integrated at the end of February, had been subjected to great strain.

The 56th Infantry Division, 134th Infantry Division, and 4th Panzer Division of the German XXXXI Panzer Corps were situated along the line: Sdredichi-Nagaya-Dubenka-Goritsy-Afonasovo-Point 232,1 (north of Petukhovka)-Polanski-center of Vesniny-Lyubovka-Dudorovskiy-Ktsyn-Moilovo-Khotkova-Klintsy and so on.

Both sides endeavored to withdraw units from the line for rehabilitation by spreading other units more thinly along their respective fronts. They also endeavored to bolster the fighting power of the units remaining in position by intensive construction of fortifications. But they immediately sought to destroy particular enemy installations and to hinder each other's preparations for attack. Static warfare began, with all its peculiarities.

During the month of May 1942 the 4th Panzer Division of the XXXXI Panzer Corps was pulled out, the 134th Infantry Division became the left flank division of the LIII Corps, which had its command post at Bolkhov, The unit adjacent to the 134th Infantry Division on the left now was the 311th Infantry Division. The southern edge of Moilovo continued to be the left boundary of the sector of the 134th Infantry Division.

On the enemy side the Russian command made efforts to pull out the remnants of the seven Russian infantry divisions (at least five of which were of Siberian origin) which had been decimated in front of the lines of the German 134th Division during February and March, and to re-form these units. Upon completion of these measures, the main body of one Russian infantry division (number no longer known), which had its command post in the northern part of Ulyanovo, was situated in front of the lines of the 134th Infantry Division, and elements of another Russian infantry division were situated in front of Dudorovskiy. The number of this latter division and the location of its command post is no longer known to the author, but the command post is likely to have been situated in the Nikitskoye-Dubna area, since from there good communications existed to Kozielsk. where the army command post was located.

Tactical Disposition (see map)

Right boundary of 134th Infantry Division to 56th Infantry Division: Forest edge at Afonasovo.

Right sector: 446th Infantry, right boundary same as divisional boundary; left boundary at Point 217.6 {one kilometer north-west of Polyanskiy).

Central sector: 445th Infantry, right boundary see above; left boundary (with 439th Infantry) at northern edge of Lyubovka.

Left sector: 439th Infantry, right boundary see above; left boundary same as divisional boundary at southern edge of Moilovo.

Alignment of the German Main Line of Resistance

Northwestern point of Grabkovo (56th Infantry Division)-Point 226.0 northwest of Afonasovo (446th Infantry)-Point 232.1 north of Petukhovka-Point 237.1 northeast of Polyanskiy-northern edge of Polyanskiy-Point 217.6-eastern edge of Vesniny-road fork in the northeastern part of Vesniny-nortbern edge of Vesuiny-northwestern edge of Vesniny-easturn edge of Lyubovka-eastern edge, northeastern tip, northern edge, northwestern edge of Dudorovskiy-road from Dudorovskiy to Ktsyn-bridge east of Ktsyn-eastern edge of Moilovo (311th Infantry Division).

Organization of German Artillery

One light battalion was assigned to the sector of each infantry regiment.

Two batteries of a heavy battalion were assigned to the left portion of the sector.

One heavy (?) battery was assigned to the 446th Infantry and moved into position west of Vesniny.

One group of lOO-mm guns was moved into position south of Moilovo.

This disposition permitted a concentration of artillery fire from, at least five batteries in front of every company sector. It also insured the cooperation of the divisional artillery of the adjacent divisions at the boundaries, In the Vesniny sector, the focal point of the defense within the divisional sector, it was possible to concentrate the fire of the entire divisional artillery, to which the guns of two captured position artillery battalions were added in the course of the summer. German and captured Russian 100-mm guns had a range as far as and including Ulyanovo.

The divisional command post was situated in the forest two kilometers west of Bobrovka.

Russian Organisation

One divisional command post was situated in the northern part of Ulyanovo.

One infantry regiment was situated in a sector including the southern part of Krapivna and the area east thereof.

One infantry regiment was situated in an area including the western part of

Krapivna, Simovka, the northeastern part of Vesniny, and the area east of Lyubovka.

The boundary of the divisional sector was probably situated at Point 229.2 (one

kilometer north of Lyubovka).

One infantry regiment (the adjacent division's regiment on the left) was situated in the sector around Dudorovskiy and up to the area east of Moilovo.

Location of the Russian Main Line of Resistance

In front of the sector of the 446th Irfantry the Russian main line of resistance was about three hundred to five hundred meters distant from the German lines. Krapivna itself was built into a strong base.

In front of the sector of the 445th Infantry the distance between the Russian and the German lines varied greatly. The north-eastern part of Vesniny was in Russian hands; there, the distance between the trenches was less than one hundred meters. In the sector of the 439th Infantry the situation was as follows: in the forest, each side merely had its system of strong points, with the distance between the systems varying greatly; around Dudorovskiy the distance between the linec varied between two hundred and five hundred meters; beyond this town there were again systems of strong points, continued along both banks of the Cherebet River.

Organization of the Russian Artillery

As late as the middle of May 1942, at least one battalion of Russian artillery was

situated east of Krapivna and in the southern part of Krapivna. Another battalion

was situated in the north-western part of Krapivna. At least two battalions (it was

never determined to which divisions they belonged; they probably included elements

of artillery reserves or artillery from other divisions) were situated in the

forest north of Krapivna, which was termed the "artillery forest". One to two

battalions were situated in the area around Dudorovo.

It is quite possible that these artillery forces still contained substantial

elements of the Russian divisions decimated in front of the lines of the 134th

Division during the defensive battle of the past winter, until these elements were

pulled out for rehabilitation of their divisions.

Terrain Description

The terrain was slightly undulating hilly country. The highest elevation in it was Hill 237.1, which was not very conspicuous and which was covered with dense vegetation. Its lowest depressions are the Reseta and the Vytebet River Valleys with an altitude of approximately 150 meters above sea level.

Like a Russian Chemin des Dames,* the town of Vesniny and the "Telegraph Road," which had been hotly contested in the winter battle, rose above the combat zone.

[* - The Chemin des Dames is a road running on top of a ridge in northeastern France between the Aisne and Ailette Rivers. It was hotly contested during World War I, particularly in April and May 1917.]

The forest in the area around Dudorovskiy was swampy, typically Russian jungle with very dense underbrush. The oldest trees in this forest, which contained pines, birches, and beeches, were probably sixty to eighty years old. Even T-34's were able to pass through these jungles only by means of previously cut "tank lanes."

The road network consisted only of usually swampy forest and field tracks, which, with the exception of those on hills, did not even dry out entirely in midsummer, so that an extensive construction of corduroy roads was vital for the troops. Only the broad sand tracks leading from Ktsyn to Dudorovo through Dudorovskiy and from Krapivna to Ulyanovo could be used by motor vehicles in summer or when they were frozen over. The sprawling villages contained shingle and occasionally straw-roofed peasant houses. The churches of Krapivna and Ulyanovo, which were visible from afar, were the only stone buildings there. The towers of these two churches were of decisive importance for the surveying and the fire control of the artillery on both sides; for this reason each side refrained, as if by tacit agreement, from shelling and destroying these towers.

The spring muddy period had turned the whole area into an extensive swamp. Summary of Tactical Events from the Beginning of May to August 1942

In their battle against the elements both sides initially tried to dig in and build cover as quickly and as well as possible. While in Vesniny the bitter, close-range fighting inside the town never subsided entirely and claimed daily victims, there prevailed in the rest of the combat zone a kind of unwritten agreement not to engage in destruction of the "billets", which both sides had taken great pains to build in order to protect themselves against the inclement weather, especially against moisture. About the middle of May, in the Krapivna area, the Russians began systematically to shell the German dugouts, engaging in an accurate bracketing and ladder fire. As the German ammunition situation had improved again since the end of the winter battle, the 134th Artillery Regiment responded by opening systematic fire on the Russian artillery, based on sound ranging and aerial photographs taken by planes of the aerial reconnaissance squadron of the corps. Depending on what reconnaissance results or firing data were available, and assisted by the sound-ranging battery or the reconnaissance pianos adjustment fire was conducted or ground adjustment fire was used, followed by a steady fire for effect.

In the beginning of June, there was Russian artillery only north and east of the Cherebet River in the so-called "artillery forest" and on both sides of Dudorovo. At the end of June, no Russian battery positions were active any longer, even in the "artillery forest."

A remarkable fact during the whole period was that the Russian artillery rarely

fired at German artillery positions, and even if it did, it hit only those

positions from which the Germans had already fired during the winter battle and

which they occasionally used again as alternate positions for specific fire

missions in order not to betray the main firing positions which had been prepared

with all due care for the large-scale fighting to come. This showed that the

Russian artillery at that time had neither observation aircraft nor sound-ranging

equipment at its disposal.

At the end of June the Russian artillery opposite the lines of the 134th Division

was estimated at two, or at the most three, mixed battalions of 75-mm cannons and

122-mm howitzers. During this time the Russians directed harassing fire from 47-mm

anti-tank guns and 75-mm cannons at the villages within range and at the roads

known to them as far as Bobrovka on the one hand and the forest track from Ktsyn to

Verestna on the other. In the beginning the Russians engaged in this kind of fire

at daybreak and at dusk, later at completely irregular intervals. The fire always

came from positions which the Russians moved in and out of quickly, and which they

therefore had evidently prepared well in advance.

The harassing fire on the German lines was undertaken by 80-mm mortars and heavy machine guns, apparently according to a plan in which both the timing of the fire and the target areas had been well considered. It was designed as an unpleasant delay in the construction of the German positions and the movement of their supplies and it cost them the loss of many men and horses (the Germans used horses, because the entire area east of the Reseta River was inaccessible to motor vehicles until early July).

Occasionally the Russians added artillery fire to the fire of their mortars when shelling combat installations on the German main line of resistance and the German battle positions. The results of this double fire steadily became more and more effective. In the Petukhovka sector and at Vesniny, the German artillery observers one day noticed the fire coordination with respect to timing and areas of the fire of Russian 80-mm and 120-nm mortars and Russian artillery, particularly in the preparation of Russian advances. This coordinated fire apparently was designed to facilitate the capture of German prisoners for the Russian intelligence service, especially since the enemy had been notably stepping up his reconnaissance activity in the air and on the ground since the end of June. German soldiers were being kidnapped in great numbers. Scrupulous observation disclosed that the Russians first adjusted the fire of their mortars on a target and then doubled up the initial fire for effect from their mortars with artillery fire, which, as a result, was well-placed from the outset. The Russian artillery itself, however, was located so far to the rear that it was able to reach the German battle position only by means of long-range fire.

In this combination of mortar and artillery fire one and the same artillery observer most likely directed first the 80-mm mortars and then the 75-mm cannons, or 120-mm mortars and 122-mm howitzers, or even mortars and guns in an inverse ratio to their calibers.

The Russians may have adopted this "economy measure" with respect to artillery observers because of the serious losses which their artillery suffered in 1941 and early 1942. Be that as it may, the measure guaranteed fine coordination with respect to timing and target areas for the fire of Russian mortar and artillery units in spite of the long signal communications to the artillery firing position, and, as a result, it affected the Germans very unpleasantly. It was rarely possible to locate; the excellently camouflaged Russian observation posts, and even if they wore located it was still very difficult to neutralize them. The sound-ranging batteries, as rule, were unable to detect the 80- and 120-mm mortars, since the sounds which their muzzle waves produced were rather low. At that time there we're no infantry sound-ranging detachments with equipment particularly adapted to these circumstances.

The Russian batteries, however, were situated so far to the rear of the Russian main line of resistance that although they were able to hit the German battle position with long-range fire, they could not, in turn, be reached by the German artillery from normal firing positions. In some cases the German sound-ranging battery did not even manage to detect these distant Russian batteries. If, however, German artillery was displaced forward and employed close behind the German main line of resistance in order to shell a Russian battery which had been located, it was very soon identified by the Russians — whether by means of sound-ranging equipment could not be determined — and was shelled by 80-mm and 120-mm mortars (the latter had a range of six kilometers), against which it was helpless, and, in addition, was taken under fire by Russian artillery. This was a very unpleasant situation.

On the other hand, when the Germans were attacking, the Russian artillery was always in a position to support its infantry by shelling any assembling German forces which had been identified and by firing a barrage in front of the Russian main line of resistance and shelling any German penetrations into the Russian battle position. Thus, the Russian artillery was protected by Russian mortars, while the Russian artillery itself, in turn, protected the Russian mortars and the infantry. Later on, information supplied by Russian prisoners of war confirmed German conjectures.

When the Russians conduct a defense with weak artillery, especially on the broad

front, mortars of the infantry and elements of heavy machine gun units are attached

to the divisional artillery in addition to the heavy mortar battalions which are

regularly assigned to the artillery. Then the fire of all these units is controlled

according to a single plan. Probably the same also applies to those infantry gun-

howitzer batteries which are organic to infantry regiments. It was impossible to

determine, however, whether in this case also the mortar units were always placed

under the command of the artillery units with regard to fire control, as had been

established beyond doubt in front of the lines of the 134th Infantry Division.

The quantities of ammunition at the disposal of the Russian artillery varied

greatly. The 80-mm mortars had virtually inexhaustible ammunition stocks, while the

flow of 120-mm mortar ammunition seemed to stop occasionally. The supply of 75-mm

and 122-mm artillery ammunition was certainly subject to very great fluctuations;

at that time it clearly indicated the points of main effort of Russian combat

activity. In view of the conditions prevailing at that time, the Russian artillery

was greatly benefited by being provided with a good map on a scale of 1 : 50,000,

which had been kept secret up to the beginning of the war.

This map made it possible for the Russians to harass the Germans with all types of

accurate fire, since by studying the map they were able to guess at the location of

a great many targets. Their progressively improving knowledge of German habits

aided them in this. All that was needed then was to check their guesses by any one

means of reconnaissance, such as scouting agents sent across the lines, in order to

be able to take the target under accurate fire.

Owing to the great width of the sectors — the sector of a German company was two to

two and a half kilometers wide, with the combat strength of the company ranging

between forty and sixty men — it was impossible to prevent Russian scouting agents

from crossing the lines, especially in terrain covered with dense vegetation, In

two known instances the Russians again used artillery observer? who were located

behind the German battle position and had radio communications. The Russian

artillery directed excellently adjusted fire at all targets which the observers

were able to see, and this lasted until the observers were tracked down and killed.

It was impossible to get the better of these Russian artillery tactics by any one

measure. Only well-devised and radical large-scale measures could bring about the

urgently needed change.

Initially, all the reconnaissance results obtained through artillery observers, the observers of the heavy infantry weapons, by means of sound-ranging, flash-ranging, aerial observers, aerial photographs, infantry patrols, and also that obtained in interrogations of prisoners and deserters was gathered and evaluated first in each sector, and than in a central agency. If necessary, information was exchanged by the sectors. In other words, the data was first compiled at battalion headquarters, then at the headquarters of infantry regiments and of the artillery battalions organic to them, then at the headquarters of the artillery regiment, in a carefully organized artillery intelligence section, and finally at the intelligence section of the division,

The results of the reconnaissance were not translated into action immediately, but as each individual situation required, by simultaneous and sudden concentrations of the fire of three batteries against different targets. The infantry gun companies and the heavy weapons companies of the infantry battalions, too, were occasionally employed for such sudden concentrations, in which case they were required to coordinate their action with the commanders of the organic artillery battalions or were even attached to the latter. In the face of these sudden German concentrations, which were executed by a constantly increasing number of weapons to the extent that thr ranges of the various weapons allowed, the above-described combat, Method of tho Russian artillery and the Russian mortars failed, especially as a large variety of weapons and mixed types of ammunition were used, including the application of smoke screens in front of suspected Russian observation posts. The decisive factor in this was probably the destruction of Russian telephone communications. To what extent this factor will continue to be important in view of the equipment with radiotelephones, which is undoubtedly also progressing in the Russian Army, cannot be estimated.

How a sudden concentration, placed not only on artillery targets but on targets of various kinds, is prepared and executed in a static situation, what results it may have and what damage it may do even to the enemy's command apparatus is explained by the following extract from my recollections which I wrote in the years from 1946 to 1948:

"Whereas it had previously been the practice, whenever enemy targets had been

identified either to shell them immediately or as part of the daily fire missions

or service practice of all weapons, the division now gave orders not to fire at

targets which did not disturb German measures and work projects, unless permission

to do so had been obtained from the divisional operations officer, but rather to

keep them under continuous observation and enter them into a special target card

file. After a few days, all sectors, the divisional intelligence section, and the

artillery intelligence section of the artillery regiment had a varied collection of

all kinds of targets, such as combat positions, command posts (the locations of

which were soon confirmed again and again by deserters), Hold kitchens,

transloading points for ammunition and rations, telephone centrals, the quarters of

small sector reserves, and so on. Even the billet of my "colleague on the other

side" appeared in the data, although unfortunately only once. The

data also included a few firing positions of heavy infantry weapons

and of batteries.

"Now the commanders of, I believe, the 13th Company of each infantry regiment were called and each of them was handed the appropriate part of the target file maintained at the divisional intelligence section and at the headquarters of the artillery regiment. At the same time, the commanders were warned that any discussion of the subject over the telephone was prohibited. Then they received orders to work out a plan for harassing fire in each sector and maintain it up to date. This harassing fire was to be started only upon receipt of a special code word from the division. As a matter of principle, one high-angle weapon and one heavy machine gun were to be directed at every target within the range of the machine guns, and the employment of all other weapons, such as antitank guns, 32-mm rocket projectors, heavy infantry guns, heavy mortars, and also that of sharpshooters, rifle grenadiers, and so on, was permitted with the understanding that every possibility of integration was to be exploited.

"The artillery received similar orders to integrate the various gun types and calibers. On the rides which I undertook on horseback every second or third day to various battalion and company command posts and on my subsequent visits to the main line of resistance, in which I found relief and relaxation from petty 'red-tape warfare,' I checked on these operations, My highly esteemed division commander in those days, whose opinions always coincided with mine, a thing which was not always to the best of all interests, did the same on his daily visits to the front. There were many men who were increasingly puzzled, wondering what all this meant. The artillery, under the command of a popular and very competent Austrian Colonel, as usual accomplished its share of the mission with great energy.

"The 'front,' however, seemed about to go into hibernation. Rarely was a shot fired, and if there was, it was usually fired by the brave, indefatigable German sharpshooters, who were always free to fire at any target within their sectors. But everywhere men were sketching and calculating!

"In early October a warning was received that action by the Russians might be expected on 'Red Army Day,' which, I believe, was either 5 or 7 October, At that, the divisional commander and I simultaneously sang out the joke in vogue at the time; 'Adelheid, it's time to fight.' We decided then and there to commemorate Red Army Day in our own way.

"On the afternoon of the day preceding the Red Army Day I issued the following

order: 'Conference call: Connect all lines down to company level! Fire control

officers to the phone!' When everyone was on the phone five minutes later I sensed

the men's high tension by their voices. Then I ordered: 'Attention! Attention!

Fire control! Code word»...! Report when ready for action! Leading Battery:

Friedrich (the center heavy field-howitzer battery)! Synchronization of watches! I

shall be back on the line in forty-five minutes. Code name.'

"As I was told later, everyone went to work with great gusto, some of the men even

with 'savage yells of glee' (was it the influence of the nearby jungle?). Within

fifteen minutes all sectors, all heavy weapons, and all batteries had reported that

they were ready for action. This was an excellent achievement on the part of the

troops and the signal personnel, especially since for some of the heavy infantry

weapons a change of position was involved and the light machine guns which were

employed were of a type that required the use of range poles for the adjustment of

their aim. One mortar battery and one 150-mm cannon battery of GHQ artillery also

participated. Unfortunately the corps had provided these batteries with only two

units of fire* for this action.

[* - Prescribed number of rounds permitted.]

"At sunset, after she stipulated forty-five minutes had passed, another conference call was sent out, this time the 100-watt fire control transmitter of the artillery regiment, which was controlled by the divisional signal battalion, and was coordinated with it. After the roll of all units had been called, the great moment came: 'Attention, Attention! Surprise fire! Code word...! Six units of fire for each gun! Whole Battery! Salvo: Battery - fire!'

"Over a front of more than forty kilometers — the artillery on the flanks of the two adjacent divisions participated voluntarily to conceal the divisional boundaries — hell broke loose! From the sharpshooter's rifle to the projectile of the 320-mm rocket projector everything was there, the whole gamut of the division's weapons playing their frightful tune, which yet has a beautiful and sublime sound in the ears of a soldier. After six minutes this fire ceased abruptly and dead silence prevailed. Now the reports of the results of the fire came over the telephone circuit, which was still linked up. Then the artillery began a steady fire for effect against the identified artillery targets to the extent that definite fire data were available.

"About fifteen minutes later, a few Russian ground attack aircraft and 'Rata' aircraft appeared in the twilight like frightened huns and dropped bombs at random, particularly on those villages which the division had almost entirely evacuated, and also fired their weapons, with equally little success. This was the first sign that the blow had hit home.

"Now, however, everyone was watching intently for the result of the fire. The observers at the combat outposts and those located on the main line of resistance soon unanimously reported that, as far as they were able to see, the fire had been accurate and had set off several explosions and fires. But what about the targets beyond the range of visibility? What was the accurate result?

Even within the first twenty-four hours, a number of shaken and wildly babbling

deserters arrived. In eight days we had with certainty established the following

picture on the basis of the results obtained from our intercept reconnaissance and

from aerial photographs taken by the Army reconnaissance plane squadron of the

corps, and from interrogation of prisoners of war, who were captured in a number of

raids undertaken all along the divisional front almost without losses, upon orders

from the divisional operations officer:

"All telephone lines up to the Russian division had been disrupted, some of them

will be out of order for several days.

"Three regimental command posts, seven battalion command posts, and several company command posts had suffered a number of direct hits and had been partially destroyed.

"Large numbers of observation posts and firing positions of heavy infantry weapons

had been hit and partially destroyed, several ammunition dumps and transloading

points had been demolished (these were the blazes and explosions which had bean

observed immediately after the barrage), several field kitchens and ration

distributing points had been destroyed (a particularly serious thing in Russia).

A large number of sentries on the main line of resistance had been killed or

severely injured, extensive losses had been inflicted on the troops at almost all

points on which fire had been directed.

"All these results certainly repaid the effort.

(Author is no longer able today to list in detail the results of the bombardment of the enemy artillery.)

"There is only one thing I have unfortunately never been able to find out and that is whether any of the shells from the 150-mm cannon, which were intended for 'my colleague on the other side,' reached its target.

"After this, quiet prevailed in our area for a long time...,"

In summing up the following may be said with respect to the tactics and fire control of the Russian artillery in a defense on a broad front:

1) The division artillery commander*- of a Russian infantry division directs the fire of all heavy weapons. In particular, he controls time, place, and rate of fire of the harassing fire of mortars and of the artillery — in exceptional cases also of the heavy machine guns — placed on the enemy's lines and at quarters, roads, and supply installations in his rear area. He is responsible for fire preparation and fire support in all operations. He directs the fire against enemy assembly areas and against preparations for attack. He controls the barrage fire of all heavy weapons in front of the Russian main line of resistance.

[* - Special staff Arty officer and Artillery commander at Div Hq.]

2) The mortar battalions are always placed under his command,

the mortar units of the infantry, the regimental batteries (infantry gun

howitzers), and some of the antitank guns are at least at

his disposal as far as fire control is concerned. Whether these

latter units are placed completely under his command has never been

clearly established.

3) The batteries of the artillery are normally employed so far to the rear that they are beyond the range of effective enemy fire, yet are able to direct successful fire into the enemy's battle position. To hamper the enemy's sound and flash-ranging and to reduce the effect of the enemy's weapons, the Russian artillery, if the terrain at all permitted, used the "square position." This consists of a completely covered, well fortified shelter and supply point, around which at least four firing positions are built, with the distance between the innermost gun of each position and the central point being up to two hundred meters. Those firing positions are organized to provide the most necessary cover for materiel and ammunition and to give the crews splinter-proof cover. They are used alternately} as the situation requires.

Command post, signal installations, shelters, kitchen, horse and/or motor vehicle shelter are located in the central point. The position which is occupied is connected to the signal installation by a side line. Only a skeleton crew stays in the position, the rest of the men hurry there from the shelters whenever it is necessary. By this method, in the course of time, the proper firing data is obtained by all four positions. Artillery reinforcements can at any time move into a prepared position without attracting the enemy's attention and suddenly join the action* The evaluators of the enemy's sound and flash-ranging batteries and the interpreters of photographs in the enemy's reconnaissance squadrons are thus greatly hampered in their work. The time required for translating reconnaissance results into firing data must be reduced to a few minutes if it is desired to avoid the danger of wasting precious artillery ammunition on a Russian position which has just boon evacuated, The best way to achieve this is to integrate, and for as long as possible, one heavy battery, as a control battery, with each sound-ranging battery, flash-ranging battery, and reconnaissance piano squadron. Each heavy battery exercises a control function. Ono light artillery battalion should be ordered to coordinate its actions with each of these heavy batteries. If telecommunications have been well prepared in advance, the throe batteries of each of those battalions will be able, within a short time, to reinforce the fire of the heavy batteries.

4) The Russian batteries are employed in a particularly flexible manner for such specific fire missions as firing a long-range barrage into the enemy's rear area, and shelling the enemy's artillery. The reduced weight of Russian guns is a great advantage here, especially since the Russians, in order to conceal their intentions, almost exclusively use horses for motive power and avoid use of motor veicles which are noisy and can be heard from a great distance, particularly at night and when an unfavorable wind blows. The firing positions for these missions had been very well prepared so that little time was required to start firing.

5) No standard can be given for the amount of ammunition used in the various forms of fire, such as harassing fire, fire for effect, barrage fire, since it varied too greatly. Nevertheless, it was always a definite indication as to the point of main effoit of the Russian operations. For this purpose it is advisable to record accurately the activity of the Russian artillery, breaking it down by day, hour, firing battery, target, type of ammunition and amount of ammunition used, beginning and ending of firo. Recording of these statistics by clay or week on overlays on the same scale as the situation maps greatly facilitates the gathering of information.