Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

GERMAN EXPLOITATION OF ARAB NATIONALIST

MOVEMENTS IN WORLD WAR II

by Hellmuth Felmy and Walter Warlimont

FOREWORD

by Generaloberst a.D. Franz Haider

German exploitation of the Arab nationalist movements in World War II extended from the field of strategic planning at the highest levels of command to the military measures actually taken. General der Flieger Helmut Felmy has presented an account of the military measures taken by Germany. Under the terms of Hitler's Directive No. 30 of 23 May 1941, and the "Service Regulations for Special Staff F" of 21 June 1941, General Felmy was appointed as the central authority for all Arab affairs concerning the Wehrmacht. Of all contemporary authorities on the subject still available, he therefore has the most thorough knowledge of the military steps actually taken on the German side. Unfortunately, the men who were his most able and experienced assistants at the time were later killed in action. Thus, consultations held to verify existing documentary evidence were restricted to junior officers, some of them of Arab origin, whose experience was naturally limited.

Similar difficulties arose in the study of the political side of the problem. In agreement with the Office, Chief of Military History, this subject was to be treated only insofar as it contributed to an understanding of the concept of Arab nationalist movements and of the atmosphere in which the inadequate and unsuccessful German military measures were introduced. Here again, some of the important contemporary witnesses are no longer alive, or are not available for other reasons. In some measure this lack was compensated by foreign sources. Part One of the study, by General Felmy, therefore bears the imprint of the field commander.

Part One required supplementation through a presentation of the military-political vantage point from which the Wehrmacht High Command, as the highest strategic command authority, viewed the development of the Arab nationalist movements and from which it proceeded in its planning. Between these two levels of planning and military execution, there existed no practical effective connecting link apart from the basic directive issued by the Wehrmacht High Command. This side of the problem therefore called for a separate treatment. General der Artillerie Walter Warlimont, who at that time directed the Planning Branch of the Wehrmacht High Command, was available for the purpose. The copious documentary material available to him contained basic Fuehrer directives and studies, but furnished no details concerning the reasons behind Hitler's decisions or the measures taken. The most important participants in this field at the Wehrmacht High Command level (Canaris and Lahousen) are dead; other participants, particularly members of the SS, are not known by name and cannot be contacted. Members of the Wehrmacht High Command at lower levels proved to have had very little information on the subject.

The circumstances are similar in the related and intimately involved fields of German political decisions and measures. General Warlimont, whose research was seriously hampered by these difficulties, has presented his findings in a study which forms Part Two of the entire manuscript. Part Two is characterized by the spirit of sober detached intellectualism of the highest levels of command.

The experiences set forth in this manuscript, and the lessons drawn there from, are for the most part negative. They show how things should not be done. German efforts to exploit the Arab nationalist movements against Britain lacked a solid foundation. Occupied by other problems more closely akin to his nature, Hitler expended too little interest on the political and psychological currents prevalent in the Arab world. This explains why the German intelligence service was inadequate in an area which presented favorable opportunities because of friendly contacts of long standing. The German supreme command was taken by surprise by the uprising in Iraq. The essential military conditions were lacking for the overhasty attempts then made. In the diplomatic, propaganda, and military fields, Germany had neglected to prepare the ground for a serious threat to Britain in the area of that country's important land communication route between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean. Germany’s belated end feeble efforts were doomed to failure from the outset against a Britain served by an excellently functioning intelligence service, valuable bases, and immediately available military forces.

Secret doubts as to the possibility of success for German military improvisations in the Arab regions probably contributed toward the remarkable degree of inactivity displayed by the top levels of German command. One thing is certain, that individual actions were duplicated by the most varied agencies, but that no uniformly thought out plan was developed for the exploitation of the Arab nationalist movements. The military efforts made were examples of inadequate and half-hearted measures. They finally deteriorated to the point where Arab volunteers were accepted as substitutes for unavailable German combat personnel.

If the measures taken at both levels—strategic planning and practical implementation—can thus be considered essentially as a lesson in omission and inadequacy, the experience gained with Arabs in the psychological field can in contrast be considered profitable. The results ere portrayed plastically by General Felmy. The deductions which can be drawn from these results are still valid in our present day.

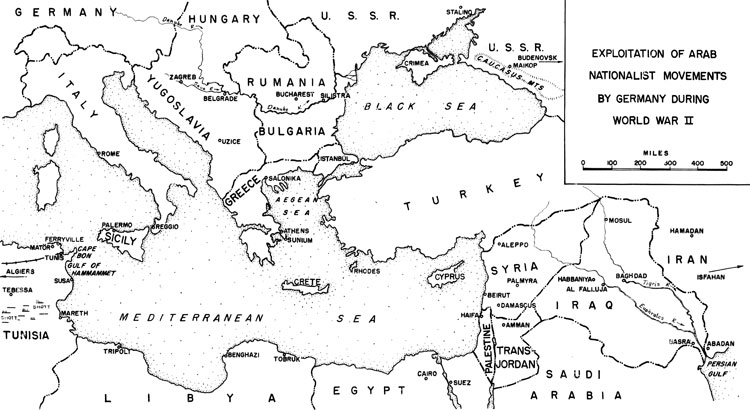

MAP 1. EXPLOITATION OF ARAB NATIONALIST MOVEMENTS BY GERMANY DURING WORLD WAR II

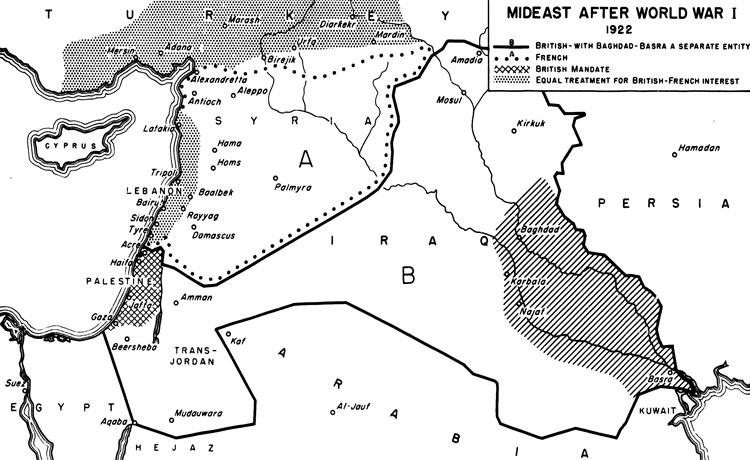

MAP 2. MIDEAST AFTER WORLD WAR I, 1922

GERLAN EXPLOITATION OF ARAB NATIONALIST

MOVEMENTS IN WORLD WAR II

PART ONE by

General der Flieger Hellmuth Felmy

CHAPTER 1

I. THE POLITICAL BACKGROUND

The defeat of Turkey in World War I brought in its wake the question or who was to rule over the Asiatic provinces of the former Ottoman Empire. After some bickering between the victorious Allies, Russia obtained Armenia and Azerbaidzhan. The Sykes-Picot Agreement, concluded between England and France in 1916, stipulated that certain territories were to become British and French administrative zones, while the rest of Arabia was to be divided into British and French spheres of influence.

During the years following the war the Sykes-Picot Agreement involved the British in serious difficulties because it was not compatible with previous agreements made with Arab chieftains. The already tense situation in the Middle East was further complicated by the emergence of Jewish nationalistic aspirations. Arab hatred of the Jews and disappointment of the Arab hopes for independence led to bloody riots. At first purely anti-Jewish in nature and directed against the rapidly increasing Jewish immigration in Palestine, the uprisings were later aimed at Great Britain as the mandatory power.

The situation continued unsatisfactory until the outbreak of World War II, when it was overshadowed by the crisis in Europe. When England declared war on Germany the Zionist organizations, which had actively supported the influx of Jewish immigrants in Palestine, at once proclaimed solidarity with Britain against Germany.

During World War I Germany had been an ally of Turkey. Her interests in the Middle East were mainly in the economic sphere. She was active in the construction of the Baghdad railway end participated in the production of oil. Nowhere in the Middle East did Germany have interests similar to those of Great Britain and Prance. Thus her position remained unaffected by the events which took place in the period between the two wars. In fact Germany enjoyed a degree of confidence among the Moslems seldom manifested toward unbelievers.

As was inevitable, the victories achieved by the Third Reich in 1940 had repercussions in the Arab world.

II. THE UPRISING IN IRAQ

On 1 April 1941, the day after Field Marshal Rommel started his offensive in eastern Libya, a large-scale uprising took place in Iraq. The regime of the pro-British Regent Abdul Illa was overthrown. During the following days the Emir Sharif-Sharaf was appointed Regent and a new government was set up with Rashid Ali as prime minister.

As far as Great Britain was concerned, the fall of the government in Iraq, constituted a crisis of the first magnitude. The hostile attitude of the Iraqis endangered the Empire's oil supply and shook the foundations of the British position in Arabia. Troop reinforcements were sent to Iraq from Egypt and India, in defiance of a treaty between Great Britain and Iraq which stipulated the number of British troops allowed on Iraqi soil. On 28 April 1941 Rashid Ali refused permission for two additional troop ships to land at Basra before a first contingent, which had disembarked on 18 April, had left the country.

When the British disembarked their troops in spite of the Prime Minister's protests, 9000 lraqi soldiers, supported by artillery, occupied a plateau overlooking the British airport of Habbaniya, some 65 miles west of Baghdad. On 1 May the Iraquis moved additional artillery into position and threatened to fire on any British personnel or planes attempting to leave the base. The British thereupon announced that they would regard any interference by Rashid Ali’s troops as an act of war. The outcome of the situation was that the Iraqis promised not to start shooting first. This irresolution on the part of Rashid Ali caused his downfall.

On the evening of 1 May Air Marshal Smart, the Royal Air Force Commander in Iraq, decided to force the issue. A telegram from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill reading "If you have to strike, strike hard," strengthened Smart in his decision. At dawn on 2 May the British attacked. Iraqi artillery immediately responded with fire on the airfield, while Iraqi aircraft from Baghdad bombed the installations. However, there could be no doubt about the outcome of the unequal contest. The Royal Air Force quickly proved its superiority, and the Iraqi resistance began to slacken. During the night of 5 May the Arab troops withdrew to Al Falluja.

Iraq had broken off diplomatic relations with Germany at the beginning of World War II, but had not declared war. Now Rashid Ali sent an urgent appeal for assistance to Berlin, where the Wehrmacht High Commahd held a conference on 6 May 1941 to discuss measures to be taken to support the rebellion. It was decided to give Iraq all assistance possible and to intensify the war against Great Britain in the Middle East. Diplomatic relations between the Third Reich and Iraq were resumed. The former German Ambassador to Iraq, Dr. Grobba, returned to Baghdad.

Even so, the only direct and immediate support that Germany could give the regime of Rashid Ali was in the form of air forces. A squadron of Me-110 fighter aircraft and a squadron of He-111 bombers were made available for this purpose. In addition, 750 tons of weapons and ammunition were made ready for shipment to the Iraqis. Plans were also made to send a German military mission to Baghdad.

The Vichy French government granted Germany permission to land planes or] French airfields in Syria, and also declared its willingness to furnish Iraq with weapons and ammunition from the stores of the French Army of the Levant. Dr. Rahn, a member of the German Embassy in Paris, was entrusted with the task of organizing the transport of the war materials from Syria to Iraq. On 10 May 1941 he arrived in Beirut, having conferred with Dr. Grobba, the Ambassador, en route. Dr. Rahn quickly gained the confidence of General Dentz, commanding the Vichy French forces in Syria. As a result of his intercession, the first train loads of weapons and ammunition for the rebels moved in Mosul on 13 May. Additional war materials followed on 26 and 28 May.*

[* - Dr. Rahn has written a detailed account of his activities in Syria from 9 May to 11 July 1941 (X-410, Rahn-Bericht). (A copy of this report is believed to be in the files of Office, Chief of Military History, DA. Washington 25, D.C. Ed.)]

The Luftwaffe bomber squadron received orders to fly to Syria on 8 May. This unit had been held in readiness on the island of Rhodes off the Turkish coast, the Luftwaffe having intended to use the planes to bomb the Suez Canal. Before starting out for Syria the squadron flew to Silistra, in Rumania, where the aircraft were given a complete overhauling.

The Luftwaffe personnel were issued tropical uniforms and equipment on the return trip, at the Tatoi Airport north of Athens. The pilots were poorly briefed, because of the general haste and in the absence of all news from Iraq. However, the German bombers were crammed with ammunition, rations, tents, and spare parts and sent en their way. Plying via Athens and Rhodes, they landed on 12 Kay in Damascus where a flight of lie-110’s had preceded them.

Dr. Rahn advised against continuing on to Baghdad because of the lack of news, so that same morning five bombers and three fighters flew to Palmyra where the French had an air base.

Finally, on 15 May, the Germans were able to make a first reconnaissance flight over Iraq. They followed this the next day by bombing Habbaniya. A total or six bombing raids were carried out on the British air base. Then the bombers had to halt their attacks, partly because the Royal Air Force had destroyed a number of ire man aircraft en the ground but also because of the death of Major von Blomberg, a son of the Field Marshal. This officer had been charged with coordinating the activities of the Axis air squadrons with the Iraqi forces. Just as his plane was about to land on the Baghdad airfield, Major von Blomberg was killed by Iraqi antiaircraft fire. In consequence there was no contact between the German and the Iraqis.

In the south the British moved in reinforcements from Palestine, Trans-Jordan, and India. On 19 May they captured Al Falluja and a bridge over the Euphrates. The Iraqis, counterattacking with vigor, retook the city on 22 May, and then lost it again when the British renewed their attack. For a few days the British were held up by string floods, but on 30 May, they advanced in two columns under the command of major General Clark to within sight of the suburb of Baghdad. The total strength of this British Force was 1200 men, 8 artillery pieces, and a few armored cars.

The Iraqis had a division stationed in the neighborhood of the capital, but made no attempt to commit it. Since the British enjoyed superiority in the air, the ill-timed Iraqi unit commanders were in no position to put up a fight. They had had an excellent chance to deal the British a telling blow at Habbaniya, and had failed to take it. The beating they took at Al Falluja had resigned them to the worst.

Thus the Iraqi uprising collapsed. When the government fled, the mayor of Baghdad capitulated to the British. On 31 May 1941 an armistice was concluded. The following day the ex-regent of Iraq, the pro-British Abdul Illa, returned from exile and formed a new government.

While these events were taking place, General der Flieger Hellmuth Felmy had been named Chief of the German Military Mission to Iraq. The instructions from Hitler activating the mission were dated 23 May, by which time all chance of effective Axis intervention had parsed. After setting in motion the organization of the mission in Berlin, General Felmy journeyed to Athens arriving there on the evening of 28 May, and reached Aleppo (Syria) on 1 June.

By that time the uprising in Iraq had been quelled. There was no contact with Baghdad, but because of reports (which subsequently proved to be false) that the British were fast approaching Mosul, the Few German aircraft on the field were flown to Rhodes. On 31 May the squadrons (which had in the meantime received a number of aircraft to replace those they had lost) were recalled to Aleppo, and on the following day General Pelmy assumed command over all German air forces based at the Aleppo airfield. Barely three days later the Wehrmacht High Command ordered him to return to Athens immediately, and to bring with him the crews of the planes, the reasons being that the British were said to have threatened to invade Syria if the Germans remained in the country.

The chief reason for the failure of the Germans to provide the Iraqis with adequate assistance in their struggle against the British was the lack of political foresight shown by the German Government. However, it would have been helpful if the Iraqis had tried to arrive at an arrangement with Germany before the start of the revolt. Effective assistance could have been given if, for instance, prior arrangements had been made by the middle of April. Then the German Army, which entered Athens on 27 April, could have struck in the first days of May. As it was, the Wehrmacht High Command did not summon a conference to discuss aid to the insurgents until 6 May, by which time it was much too late. Such measures as were finally taken were completely overshadowed by the preparations for Operation Barbarossa.

On 26 May 1941 Mussolini, through the of offices of the German Military Attache in Rome, expressed his views on the situation to the Wehrmacht High Command:

Token assistance will not serve the interests of Iraq. I am for active support. The need is for aircraft, guns and tanks. This is our chance to rouse the peoples of the entire East against Great Britain. If no assistance materializes, they will lose courage. Using Rhodes as a base we can take Cyprus. Once Cyprus and Crete opposite the Syrian coast, are occupied, we will hold the key to the entire Orient. It will then be only a matter of time before the British have to live up their naval base at Alexandria. If, however, we find that we are unable to furnish Iraq with effective assistance in time to turn the scales against Great Britain, then it would be better to inform Rashid Ali accordingly.

Mussolini’s summing up of the situation pointed up the real reason behind Britain’s fears. However, again, it was too late to put these ideas into practice.

Meanwhile Great Britain had been given. a welcome excuse to invade Syria because of the temporary loan to Germany of French air bases and the possibility that German forces might infiltrate into that country. Accusing the Vichy government of having surrendered to Axis domination in Syria, British and free French forces launched an invasion from Palestine, Trans-Jordan, and Iraq on 8 June. On 21 June they captured Damascus, the Syrian capital.

CHAPTER 2.

I. THE GERMAN-ARAB TRAINING BATTALION IN GREECE

Following the recall of the German Military Mission to Iraq, General Felmy proposed to the Wehrmacht High Command that the mission be retained on an active status because the specialists comprising the mission personnel would be difficult to replace. At the same time he suggested that it would be advantageous to create a modern motorized training battalion to instruct Arab officers and noncommissioned officers.

Both proposals were accepted by the High Command. At the Doeberitz training grounds near Berlin a start was made in organizing a training battalion to meet the above purpose. As a result the Military Mission, redesignated as "Special Staff F” found itself faced with a number of new tasks. These tasks were defined in Directive No. 32 and the "Instructions for Special Staff F", both issued in June 1941.

These two documents designated Special Staff F as the central Wehrmacht agency for all questions affecting the Arab world. The instructions directed the activation of the 288th Training Battalion at Doeberitz and the assignment of a "Liaison Staff Syria" to the Vichy forces under General Dentz, which were resisting the British invasion of Syria. The chief of staff of Special Staff P, accompanied by a number of assistants, was dispatched to Beirut, where he joined Dr. Rahn and functioned in a capacity similar to that of military attache.

At the time of the Iraqi rebellion a number of Arab students residing in Germany had volunteered for duty in the Wehrmacht. The Wehrmacht High Command, Foreign Group, had arranged for them to receive a four-weeks training course in Dueren, in West Germany. About 30 Arab volunteers were transferred from Dueren to Special Staff F as the cadre for the promoted German-Arab training battalion. The area of Sunium, on the southernmost tip of Attica in Greece, had been selected as a training ground for the battalion. Permanent quarters were to be established in the weekend villas of wealthy Athenians, but the majority of the personnel were to live in tents. Since the climate was sub-tropical this was no hardship.

Special Staff P and the Arab volunteers gathered at Sunium in July 1941. Training of the Moslems began immediately. The Arabs had a fair knowledge of German and showed themselves willing to learn. Unfortunately, they lacked imagination, and this made it difficult for them to understand the significance of the individual phases of a military operation. Quite a number of the volunteers could not understand why they should have to go through a toughening up process, although this is an integral part of military training everywhere in the world. The Arab attitude was that it was unnecessary to make a serious effort.

From the first, opinions varied regarding the type of training that should be given the Arabs. One mistake that was made was to use as instructors Germans who had lived in

Palestine and the other Middle East countries. These men had long been accustomed to regard Arabs as a race of menials, and something of this attitude crept into the instruction. When efforts were made to establish a better working relationship (the volunteers and their German instructors were encouraged to meet in the mess for friendly discussions about the progress of the war) the Arabs came to the conclusion that they were already regarded as full-fledged partners in the Axis.

One of the major issues adversely affecting the smooth operation of the training program was the conflict engendered by the difference in the political loyalties of the volunteers. Some of the latter professed their faith in one Arab chieftain, while the others argued the merits of his opponent. Thus a number of the volunteers had already secretly contacted Fauzi Kaikyi, the Syrian army leader. After his escape by plane from the British, Fauzi had established himself in Berlin and begun to take an active interest in the Arabs at Sunium. Despite these misunderstandings, on 24 August 1941 the volunteers took an oath to fight for “a free Arabia."

While the volunteers were receiving instruction at Sunium, activation of the 288th Training Battalion had been completed at Doeberitz. Early in October the unit arrived in Greece and took up its quarters north of Sunium. Training was thereupon considerably expanded. Due to the limited strength of its personnel, the original plan was to use Special Staff F in guerilla-type warfare in the Syrian Desert. Highly mobile company-strength units equipped with heavy weapons were to occupy the sites of vital water wells, demolish or capture bridges and railroads, cut the pipelines on which Britain depended for her supplies of oil, and meanwhile live off the land; since Arab volunteers, familiar with the region, were part of the special staff this was no great problem. Supplies of fuel and ammunition were to be delivered at regular intervals.

On 18 November 1941 the British launched an offensive in eastern Libya which threatened to sweep all before it. Special Staff F offered its help in stemming the tide. The Wehrmacht High Command ordered the 288th Training Battalion flown to Benghazi and attached to Rommel’s army as a blocking force. After the departure of the training battalion, the instruction at Sunium was curtailed and tailored to meet the requirements of the small body of Arab volunteers.

On 26 January 1942 a Captain Schober assumed command of the German-Arab training battalion. The volunteers were issued German uniforms and an arm band inscribed "Free Arabia." The psychological effect was excellent; the Arabs now regarded themselves as real soldiers and as bona fide members of the German Wehrmacht. Also attached to Special Staff P around this time was a company of Germans who had fought in the Trench Foreign Legion in Syria. These men were excellent fighters, but they were rather difficult to handle. They were poorly suited to instruct the volunteers, moreover, since their French training had given them a low opinion of the Arabs. Finally, in April 1942 a contingent of 105 Arabs arrived to swell the ranks of the instruction unit, A number of them had been in German prisoner of war camps. Originally they had come from Syria, Saudi Arabia, Trans-Jordan, Palestine and Egypt. While the training of the original 30 Arab volunteers continued, the newcomers—who had already been in action— were formed into a separate company.

During the following weeks, training at Sunium was standardized. Instruction covered individual combat and small unit tactics, practice with machine guns, bazookas, infantry

howitzers; and mortars, demolition, construction of antitank obstacles, driving, field exercises with live ammunition, and night problems. Instruction was in German, though German officers had received instruction in the Arabic language. At the end of March, the first part of a German-Arabic military dictionary was published in an attempt to reduce the various Arabic dialects to a common military denominator. A "Manual for the draining of Squad Leaders in the Arab Liberation Corps" went to prase at the end of July.

On 9 July 1942 Special Staff F, in agreement with the Wehrmacht High Command and the Arab leaders who had taken refuge in Berlin, promoted fifteen of the original thirty Arab volunteers to lieutenants. Four core were raised to sergeants first class and two to sergeants. By and large, the promotions did not achieve the desired effect. It had been hoped that they would raise the morale of the training battalion as a whole, and that the new officers would fit smoothly into the German conception of soldiering. However, the Arabs did net seem to understand that promotion entailed additional responsibility. Nor was there any evidence that they were aware that a common interest linked all Arab tribes, and that they should therefore integrate their efforts.

Meanwhile, Special Staff F had become aware that the Arab "Big Two" in Berlin were competing for power. The German Ministry for Foreign Affairs regarded Rashid Ali, the ex-Prime Minister of Iraq, as the legitimate representative of his country. This annoyed the Grand Mufti, the Moslem spiritual leader. He regarded himself as representing Islam as a whole, and was consequently unwilling to yield precedence to Rashid Ali. Special Staff F understandably had no desire to take aides because its interests were purely military. Yet the conflicting issues which set Arab against Arab began to threaten the staffs effectiveness.

Each of the Arab Big Two was surrounded by a court into which part of the Arab volunteers had been drawn. Life in Berlin and Rome—the Grand Mufti was spending part of his time in the latter city, where he had connections—seemed far more attractive to the volunteers than the hard training at Sunium. Rashid Ali and the Mufti had both agreed that it would be a good thing to promote some of the volunteers, but like the rest of the Arabs they failed completely to appreciate that promotion meant greater responsibility. The two Arab leaders could not be persuaded to discontinue the intrigues which undermined the common effort. It is difficult to say whether the two rivals saw a future instrument of power in the German-Arab training battalion, but the fact remains that neither Rashid Ali nor the Mufti wholeheartedly supported Special Staff P.

II. ACTIVATION OP ADDITIONAL SPECIAL UNITS

During a series of conferences which took place in the spring of 1942 at the Wehrmacht High Command it was agreed that Special Staff P would receive replacements for the 288th Battalion, which had been dispatched to Rommel. Early in the summer the 287th Special Regiment was organized at Doeberitz. It controlled two German motorized battalions and the German-Arab training battalion. In addition the unit had an armored reconnaissance company, and antiaircraft, assault gun and smoke-shell batteries, so as to be able to form an effective point of main effort in battle. Adequate motorized supply services were to be assigned to the regiment before employing it in the Near East, so as to enable it to cope with the conditions imposed by desert warfare. Military authorities in Germany even considered activating five or six similarly organized purely German unite, subordinating them to Special Staff F, but since the over-all supply situation had deteriorated so greatly during the preceding summer this plan was abandoned.

Special Staff P, a thousand miles from the scene of these decisions, was able to exert very little influence on the activation of the new units. To remedy this situation a staff was created in Berlin to advise on the selection of personnel and equipment.

After the conquest of Tobruk, Special Staff F confidently expected to be employed in Africa. However, Allied air superiority constituted such a threat to Axis shipping that it was impossible for the unit to cross the Mediterranean Sea.

Meanwhile German Army Group A advanced into the Caucasus region. The first Russian oil fields were captured near Maikop on 9 August 1942. At this time Special Staff suggested to the High Command that its units be used in Russia. This suggestion was approved. Beginning 21 August Special Staff F moved from Sunium to Stalino in Russia. The 287th Special Regiment was dispatched directly from Doeberitz to Stalino, and placed under the command of the special 3taff following ita arrival beginning in September.

While this movement was under way, General Felmy and his chief of staff, together with Admiral Canaris, the chief of German Counterintelligence, held a conference in Berlin with Rashid Ali and another conference in Rome with the Grand Mufti. During these talks the future of the German-Arab training battalion was discussed. In the opinion of the two Arabs the unit should not be used against the Russians because it had been organized end equipped for the specific purpose of waging war in the desert, not for a campaign in the Soviet Union where conditions were altogether different. After some discussion, the Germans were able to set these arguments aside. The talks continued with an examination of the military measures to be taken in the event of an Axis invasion of Iraq and the adjacent Arab countries.

It was pointed out to the Moslem leaders that the political status of the Middle East countries would be a decisive factor in any such operation, and there would have to be smooth teamwork between the politicians and the soldiers. It was, after all, vital to forestall the sort of discord between various Arab factions which had developed in Sunium.

To all these ideas Rashid Ali was more responsive than the Mufti. The Iraqi willingly signed an agreement summing up the results of the conference, but the Mufti hesitated. It was easy to see that the visit he had paid Hitler that summer at the latter9s headquarters had not succeeded in allaying his fears. The declaration made by the Fuehrer on that occasion, to the effect that it was too early to settle the Arab problem and that no move could be made in the Middle East until a German army had occupied the southern slopes of the Caucasus Mountains, had not succeeded in dispelling the Mufti's skepticism.

After their meeting with the Arab leaders, Felmy and his chief of staff journeyed to the Fuehrer's headquarters at Vinnitsa in the Ukraine. Here they reported on their conferences with Rashid Ali and the Grand Mufti to a representative of the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The situation of the German-Arab training battalion was discussed at length. It was imperative to avoid further political dissension among the Arab volunteers, because in the long run it endangered discipline. As commander of Special Staff F, funeral Felmy pointed out that unless the Minister for Foreign Affairs exerted his influence to remove the causes of friction, German policy in the Arab countries might well be imperiled.

On 22 September Special Staff P was given a directive outlining a training program at Stalino for desert warfare. The directive stressed that the individual soldier must be able to fight independently, and that training should include firing practice with various types of arms, reconnaissance, observation, and orientation by the compass. Arab language instruction was to be confined to phrases for everyday use and the essentials of military terminology.

Meanwhile the offensive undertaken by Army Group A had bogged down on the north side of the Caucasus fountains, and it was too late in the year to think of continuing the offensive.

In line with, its new assignments Special Staff F was re-designated Generalkommando z.b.V. (Corps Headquarters for Special Employment) on 25 September at Stalino. Its members were given permission to wear an arm band with the emblem of a sun rising behind palm trees.

On 1 Ootober, the Generalkommando was released from Wehrmacht High Command control and attached to Army Group A for employment in the security missions. She teletype message ordering the transfer specifically stated that the German-Arab training battalion, i.e. the 3d Battalion, 287th Special Regiment, must not be employed in combat north of the Caucasus Mountains.

A few days prior to their departure from Stalino for the front a number of the Arab officers and noncommissioned officers refused to leave. Some reported sick, others simply refused to budge. An Arab lieutenant named Manfred Rolf* kept a diary during those tense days. Under date of 2 October 1942 he noted: "... attached to us are several German instructors, many of whom wear the Iron Cross First Class. Our battalion has four companies, the first three of which consist of Arabs with German instructors. She fourth company is exclusively German in composition. This company is the heavy weapons company.

[* - Manfred Rolf is a pseudonym. The lieutenant in question was from Damascus and had studied in Germany. He was one of the first volunteers in Sunium. At present he is in Baghdad.]

"A number of our men are in the hospital, but I think they are malingering. Many Arabs are looking for a pretext to leave the service. Some of them have decided to get out regardless of what happens. Applications for discharge alternate with disobedience, with the result that the culprits are restricted to quarters. Thereupon they complain to the battalion commander. There has been some violence. All this in the name of freedom! But what sort of freedom? The freedom to shed the uniform and go to parties in Berlin, or the freedom to travel to Paris, Sofia, Belgrade, Budapest or Istambul on a secret mission, the said secret mission being mainly concerned with coffee, bolts of clothing material, perfume and gold pieces. Once in Berlin I met a friend who had just returned from a 'mission’ to Sofia. He showed me four suitcases of scarce goods and then asked me whether I didn’t think he was smarter than I.

"The conduct of the battalion prompted Captain Schober, the commander, to remind them that they had signed a promise to behave. At this point a comparison of the Arab and German text of this promise showed that the Arab translation was in error.”

On 5 October 1942, the following entry in the diary was made: “... Today the General paid the battalion a visit and asked the Arab officers and NCO’s to assemble in his quarters. Using me as an interpreter, he told the men that he had received a report from Captain Schober. He then asked me to translate the report. It dealt with the situation of the Arab Freedom Corps after 1 February 1942 (when Captain Schober took over). After the three-page report had been translated, the General addressed us. He spoke briefly and to the point. He said he remembered witnessing an attack by Arab units at Gaza in 1917 and that he had been much impressed by the courage of the Moslem troops. He contrasted this courage with the defeatism shown by the Arab volunteers who had requested their discharge. In closings he said that all Moslem volunteers requesting to be separated from the service would be reported to the Grand Mufti. Furthermore their permit to reside in Germany would be revoked. He said he would give them one more chance to think the situation over. The decisions were to be made before 1800 that evening, and Captain Sohober was to report the outcome to him.

"With the exception of those few who wanted to quit at any price, most of the Arabs were dismayed. There were several meetings among the volunteers and then at 1700 Captain Schober asked each one in particular for a straight yes or no."

Lieutenant Rolf's description of the situation prevailing among the Arab volunteers is absolutely correct. For these conditions the Arab "Big Two" were chiefly responsible. The upshot of the affair was that the disgruntled elements were sent to the Wehrmacht High Command/Counterintelligence Branch under guard. Thereafter the German-Arab training battalion returned to normal.

On 6 October 1942 the Generalkommando was attached "by Army Group A to the First Panzer Ariny to cover that array's northern flank. Three days later the unit was en route from Stalino to Budenovsk, in the Caucasus. Its leading elements arrived there on 12 October. The German-Arab battalion, however, did not go with the Greneralkommando, due to the scarcity of transport. Moreover, the High Command had ordered that it not be employed in combat north of the Caucasus. For the time being, the battalion remained in Stalino, where it was moved out of its tents into better quarters. The bulk of the units of the Generalkommando arrived at Budenovsk in mid-October, just in time to repel a thrust by the Russian IV Cavalry Corps against the open flank of the First Panzer Army. With short interruptions, the fighting continued for a number of months.

III. TRANSFER 0F THE GERMAN-ARAB BATTALION TO SICILY

The landing of U.S. and British .forces in Morocco and Algeria on 8 November 1942 caused a complete reversal of the over-all situation, which had its effect on the Generalkommando. At the beginning of December the German-Arab battalion was shipped from Stalino to Palermo in Sicily. The plan was for the Generalkommando and the rest of its units to follow; however, this proved impossible because the fighting in the Caucasus steadily increased in violence. The Special Corps could not "be pulled out of the line without exposing the flank of the First Panzer Army. In an effort to retain some measure of influence on the utilization of the German-Arab battalion, the Generalkommando sent its chief of staff, Lieutenant Colonel Meyer-Ricks, to O.B. Sued (CinC South) in Italy on 7 December.

In Africa, meanwhile, the arrival of the first German troops in the Tunisian bridgehead resulted in an unexpected increase in the number of Arabs flocking to the German colors. Some of the Moslems were idealists inspired by the Arab struggle for liberation, but a substantial number of those who volunteered were simply unemployed.

In December 1942, O.B. Sued, for administrative reasons, activated a German-Arab command called Kommando deutsch-arabischer Truppen or Kodat. The following month the German-Arab battalion moved from Sicily to Tunisia to supervise the induction of Moslem volunteers. The sight of Arabs in German uniform, wearing sleeve bands with the words "Free Arabia" embroidered on them, had an excellent effect on the number of new enlistments.

In an effort to bring some order into the manses of volunteers flocking to the German colors, separate companies were organized for Tunisians, Algerians, arid Moroccans. These companies were commended by German lieutenants or sergeants and were about 150 men strong. Five ex-Foreign Legionnaires in each company functioned as noncommissioned officers. Limited quantities of uniforms, weapons and equipment were procured; billeting, rations, pay and medical care were arranged for. Training started, but a great deal of improvisation was necessary before things were running smoothly, because the tight supply situation precluded the arrival of German equipment. Very much to their dismay, the. volunteers had to make do with worn-out French uniforms and obsolete French rifles. There were no heavy weapons.

The distance separating the German-Arab battalion from the Generalkommando complicated matters greatly. It was difficult for the small German staff in Tunisia to shoulder the enormous workload which fell to its share. While the Moslem companies of volunteers were being organized, the troops of the German-Arab battalion guarded the coast of the Gulf of Hammamet from Cape Bon to Susa.

During this period by order of O.B. Sued a Captain Schacht of the 1st Parachute Regiment was appointed by O.B. Sued to organize a number of demolition squads for the purpose of blasting objectives in the enemy rear along the railroads from Algiers. Schaoht selected more than 100 Arabs from the German-Arab Command (K0DAT) for instruction in demolition and pioneering work at the Wittstock Parachute School near Berlin. In a report entitled "Employment of Demolition Detachments Behind the Enemy Lines in North Africa during Spring 1943", Captain Schacht noted: "The command (KODAT) was composed of Moroccans, Algerians, Tunisians, Senussi, Tuarege, Egyptians, Syrians, Iraqi and desert Arabs. Volunteers had to provide proof of two years of service in the army of their own country before they were accepted. Former French colonial troops were mixed with Italian Sahara veterans, British-trained fighters of the Middle East countries, and Foreign legion soldiers. One old sergeant had even served in the Turkish Army in World War I.

By mid-February German weapons had arrived in Africa in sufficient quantities, and the companies of Moslem volunteers were raised to battalion status. Organized were 2 Tunisian battalions, 1 Algerian battalion, and 1 Moroccan battalion. Each battalion consisted of three infantry companies armed with carbines and light machine guns, and one heavy weapons company equipped with mortars and heavy machine guns. Medical and signal equipment was scarce. Trucks and horse-drawn vehicles were altogether lacking.

Since the combat training of the Arabs was still in its early stages, the battalions would not be an effective fighting force for some time. Unfortunately, the training was interrupted suddenly when the Generalkommando’s chief of staff, Lieutenant Colonel Lieyer-Ricks, and the comnander of the German-Arab battalion, Major Schober, were killed during an attack by low-flying aircraft on 24 February 1943. No replacements were available for these leaders. The Generalkommando was involved in heavy defensive fighting along the Mius River in southern Russia and so was unable to spare personnel as replacements. Although as a general rule the death of a commander did not result in the dissolution of a German military unit, in a case such as this where special conditions prevailed the loss could have serious consequences. Both of the dead officers had performed their duties well, and both spoke Arabic fluently. It was difficult to find other men who were as expert in the field of German-Arab relations. Finally a Colonel von Hippel, who had seen service in the former German African colonies, was entrusted with the command of KODAT by the Fifth Panzer Army.

From 14-22 February 1943 the Germans in Africa attacked toward Tebessa. This attack failed and it became necessary to shift to the defensive. The troops of Field Marshal Montgomery, advancing from Tripoli, slowly approached German positions around Mareth. By mid-March the situation had become so critical that it was necessary to employ a battalion of Tunisian troops in the central sector of the German line. The experiment had disastrous results. The Tunisians were led up to their positions in the dark through hilly terrain. Since it was cold the combat outposts lit fires, whereupon they were taken under fire from the rear by their own troops. This alerted the enemy. The latter immediately attacked and succeeded in overrunning the Tunisians. Fifth Panzer Army Headquarters concluded from this experience that it would be better not to use the Moslem battalions in the forward areas. Instead they were employed in the rear, constructing defensive positions.

On 28 February 1943 the commander and staff of the Generalkommando was alerted for movement from Russia to another theater. Subsequently these elements of the Special Corps were transferred to Reggio in southern Italy and placed under 0.B. Sued. All tactical and headquarters units of the corps remained behind, attached to the XXIV Panzer Corps which had taken over its sector.

O.B. Sued had earlier requested two corps headquarters for use in Africa. However, when the commander of the Generalkommand o arrived at Headquarters, O.B. Sued, he had to report that his units had remained in Russia and that, without its signal units the Generalkommando was useless.

In mid-April 1943 some of the German personnel in the German-Arab battalion, and all Moslems who hail finished their training, reinforced by ex-Foreign Legion troops, were consolidated into a "task force” near Ferryville in Tunisia. This group included 2 infantry companies and 1 heavy company, the latter composed of 1 heavy infantry howitzer platoon, 1 20-mm antiaircraft platoon, 1 antitank platoon, and 1 heavy machine-gun platoon.

During the following weeks this task force was employed in the northern sector of the front, southwest of Mater and in the Sedyenane Valley. It served as the tactical reserve of an Austrian division, and later with the 999th Light Africa Division. Few details are available concerning the fighting done by the group, but it is known to have been employed next to a parachute engineer battalion under a Major Witzig. On 1 May it relieved a battalion of the 1st Parachute Panzer Division ("Hermann Goering Division"). On this date the task force successfully repelled a thrust by American units. On 3 May it acted as rear guard of an infantry regiment (commanded by an officer named Bailerstaedt?). Three days later it formed the reserve of a Luftwaffe regiment employed in ground action (commanded by Barenthin?). On the afternoon of 7 May the group was to have assumed responsibility for the protection of an antiaircraft unit established along the Bizerta—Tunis railroad. As the task force was about to move into position the antlaircraft unit was overrun by American tanks.

The following day the supply trains of the task force were disbanded, its records were destroyed, and the remnants of the group—less than 100 men—assembled at Porto Farina, north of Tunis, Here from 4,000 to 5,000 other Axis soldiers waited in well-disciplined ranks for ferries to evacuate them. The majority of the Arab soldiers in the task force remained with the German troops and went voluntarily into captivity with them.

The Moslem battalions activated in Tunisia in February had not been as thoroughly trained as the German-Arab battalion. The time and the German instructors needed to train them were both lacking, and the general situation was unfavorable.

IV. ACTIVATION OF THE 845th GERMAN-ARAB BATTALION

When the Generalkommando was transferred from Russia to Italy, it lost all of its units except the German-Arab battalion, which, of course was in Tunisia at the time. Nevertheless a Wehrmacht High Command order dated 29 March 1943 emphasized that the Generalkommando would continue to function as its field agency for Arab affairs. On 8 April the Generalkommando was redesignated Generalkommando s.b.V. LXVIII and reorganized as a regular motorized corps headquarters. The pertinent order contained a paragraph to the effect that the Special Corps was to organize a staff to deal with all political issues and propaganda connected with the Li o si era world. This staff was to serve with the German-Arab battalion.

After the Germans lost the Shott (Swamp) Position in Tunisia there was no longer any chance of utilizing the Generalkommando LXVIII in North Africa. The corps was therefore made available to O.B. Sued for employment in southern Greece. It arrived in Greece at the end of May 1943. At this time the corps was finally separated from the 287th Special Regiment, which was reorganized as the 92d (mtz) Infantry.

Meanwhile elements of the German-Arab battalion which had remained in Palermo (Sicily) while the bulk of the battalion was employed in Tunisia, were ordered incorporated into the 845th German-Arab Battalion, a unit activated at Doellersheirn in Germany en 1 June 1945.

Generalkommando LXVIII issued a training directive for this new battalion on 30 June 1943. This directive read in part as follows:

“l. The battalion is under the direct command of the Generalkommando. Initially it will organize into units all Arabs ready to serve the German cause and will train them

in guerilla tactics.

“2. For this purpose it will give the Arabs:

a. Basic infantry training,

b. Training in teamwork i'or surprise raids to be carried out by squads and half-squad size units,

c. Training in demolition techniques (ranger-type training).

"3 …If possible sq uads should be composed of men from the same locality.

...

“7. The battalion’s fifth company will be a parachute company. Lieutenant Rolf is appointed commander of this company.

...

9. Also attached to the Generalkommando is the "Arab Recruiting Center" (Westa) in Paris [See below]. At present this agency is mainly an intelligence agency.

10. After its transfer to the zone of C.B. Sued the battalion will be employed for guard duties in addition to its normal training routine."

The program stressed the training of very small units. Experience had shown that this method was successful. It was also intended to use the 100 Arabs who had already received training as parachutists in Wittstock, but somehow a parachute company was never actually formed.

The Arab Recruiting Center in Paris had been organized in 1942, because part of the Arabs volunteering for duty with the Axis came from French colonies. One of the tasks of the Center was to watch over the welfare of the dependents of these men. The establishment of a German bridgehead in Tunisia increased the importance of the Center. Naturally, under the prevailing circumstances, the office was also ideally situated to procure intelligence information.

On 30 June 1943 an "Intelligence Section for Arab Affairs” was organized to serve with the German-Arab battalion as the special staff requested by the Wehrmacht High Command. Since in southern Greece Generalkommando LXVIII commanded German unite, this Intelligence Section made preparations for the employment in Arab countries of task forces of all types, by compiling data and evaluating intelligence information in cooperation with the Arab Recruiting Center (Westa) in Paris. In addition, it made Arabic language broadcasts in coordination with appropriate agencies in the Wehrmacht High Command (Foreign Group) and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

The Intelligence Section for Arab Affairs was duly activated in July 1943 in Belgrade, where the Semlin radio station was placed at its disposal. The Germans had been able to decipher the British directive on Arab propaganda which Radio Cairo was using, and now this directive came in very handy. When the section had to move from Belgrade to Zwettel, north-west of Vienna, late in the summer of 1944, the broadcasts to Arab countries were continued by the Berlin broadcasting station, where the technical facilities were better .than in Vienna. There is no information available on the effects of these broadcasts, but Allied broadcasts—if any of them even reached Arab soldiers in the German Army—-seemed to make very little impression.

After it had completed basic training at Doellersheim early in November 1943, the 845th German-Arab Battalion was assigned to Army Group E in the Aegean area. It was given responsibility for railroad protection north of Salonika. Soon afterward Generalkommando LXVIII meanwhile redesignated Generalkommando LXVIII A.K. (Headquarters, LXVIII Corps), requested that the battalion be placed under its direct jurisdiction. This request was approved by Army Group E, with the consequence that in the spring of 1944 the companies of the battalion were transferred to the area south of lamia, and battalion headquarters was established at Anfiklia. In the warfare against Greek partisans which took place in this area, the 845th German--Arab Battalion proved its worth. It was a form of combat which seemed to suit the Arab mentality.

When the German Army evacuated southern Greece in October 1944, and retreated northward through the Balkans, the 845th German-Arab Battalion usually furnished the rear guard. Remarkably enough the Moslem troops soon became accustomed to

severe cold and even though they suffered high losses they remained effective. The German forces retreated from Greece into Yugoslavia, frequently delayed by air raids and partisans. Throughout the withdrawal the Arabs gave a good account of themselves. Toward the end of November, the 1st Company, 845th German-Arab Battalion, attacked Hill 734 at Uzice four times in succession despite the bitter cold and the deep snow. A fifth attack was successful.

In February 1945, after an interval for rest and rehabilitation, the Arab battalion was employed between the Danube and Sava Rivers. In April it participated in the retreat which brought General Hauser’s fortress divisions to positions west of Zagreb, in Croatia. Here the battalion was captured. As far as can be ascertained the Arabs were concentrated in special prisoner of war camps and released after about one year of captivity.

V. LESSONS DERIVED FROM EMPLOYMENT OF NATIVE TROOPS

A few typical examples from the experience of Captain von Voss, Commander, 1st Company, 845th German-Arab Battalion, are provided to show the type of situation frequently encountered by German officers in their dealings with Arab personnel.

One day, Ali ben Mohammed reported to the medical officer and requested that he be hospitalized. The officer examined Ali and found him in excellent health.

"Why do you want to be hospitalized?" he said. "You’re not sick."

“Others get into the hospital. Why can’t I?"

"You are healthy and you’re not going into a hospital!" All turned to the door, which had a glass panel, and pushed his head through it. Covered with blood, and with pieces of glass sticking into his scalp, he faced the doctor and asked "Am I sick enough now?"

On another day, the company was drilling. Everything seemed to be going well. Suddenly, one Machmut hurled his rifle away and flung himself on the ground. "Ich nix [sic] Soldat!" (Me no soldier1) he cried. His friend Mabruk was so ashamed at Machmut's behavior that he drew his bayonet and gave himself five to six blows over the head with it, exposing the bone under the scalp.

On another occasion two Arabs were teasing a soldier about his homosexual inclinations. That same night the soldier in question took his rifle, placed it behind the ear of one of his two tormentors, and pulled the trigger.

.During an action against partisans, Colonel von Eberlein, the commander of a security division, radioed that he was caught between two rivers. I told some of my Arabs, who were fond of the fierce old man with all the medals. All of them volunteered to go with me to the colonel's rescue. When we came to the river, they refused to let me wade across} they insisted on carrying me across on their shoulders.

My Arabs never filched any of my personal belongings, though as a rule they stole like magpies. They liked to stuff themselves with good food, they liked to get drunk, to loot and rape; but they also knew how to die bravely, and they resisted pain remarkably well.

First Lieutenant Breiden, who was in the task force of the German-Arab battalion in Africa, points out that the Arabs could have been discharged from the service after the German collapse in Tunisia and could easily have melted away into the native population. Yet the majority of the Moslems preferred to share the uncertainties of captivity with their German comrades-in-arms.

Captain Schacht of the 1st Parachute Regiment writes in a personal letter: "... In November 1944 word got around that I had been entrusted with the activation of a Parachute Regiment for Special Employment. Before the month was over approximately 100 Arabs had deserted from their jobs with various staffs to volunteer for service in the new regiment. Under the leadership of the officers who had commanded them during the Tunisian campaign, they formed an extra company for the regiment. During the fighting in March and April 1945 in Pomerania and the Oder marshes the Arab company fully proved its effectiveness. In at least two instances I owed my life to the Arabs. Their losses were in proportion to their courage."

Although there were obvious contradictions in the character of the Arabs, as depicted in the foregoing accounts, one quality never varied and that was their loyalty to their commander once the latter has succeeded in gaining their confidence. In the final analysis, of course, sound military leadership is always based on the personal relationship between the troops and their commander, however, undivided loyalty appears to be more pronounced among so-called primitive peoples. It was the Arabs from the interior, unspoiled by civilization, who made the best soldiers.

The major lessons derived by the Germans in their utilization of Arab movements may be summed up as follows:

a. The most important thing is the selection of officers and noncommissioned officers. Besides military skill, such men must have personality traits that the Arabs can admire. Character is more important than proficiency in the Arabic languages, desirable though such proficiency is.

b .Native noncommissioned officers promoted from the ranks find it difficult to command respect. Their fellow-tribesmen do not seem to regard them as quite genuine.

c. Military justice and discipline must be adapted to the Arab mentality. A delay between the verdict and its execution usually makes the punishment ineffectual. Forced confinement merely increases the Arab inclination to laziness. It seems doubtful whether corporal punishment, as practiced by the French, is still appropriate.

d. Training and the exercise of a personal influence on Arab recruits is based largely on barracks duty and dismounted drill. A little severity usually pays off; in fact, it stimulates the desire of the men to play soldier and is closely linked to the care of their uniforms, weapons, and equipment. The Arabs take great pride in their uniforms and insignia, but they frequently consider their weapons and equipment as their personal property, with the result that it is inadvisable to ask them to turn in their old weapons for new. By and large, they feel insulted when this is done.

e. The Arabs quickly learn to operate heavy weapons. Understanding the German commands presented difficulties only in the beginning.

f. The Arabs are good in terrain exercises and combat training. Here their innate hunter's instinct stands them in good stead. In reconnoitering and night patrols the Moslems were far superior to their European instructors.

g. One must not expect the Arabs to do any independent thinking or to understand what is supposed to happen during the various phases of an operation. They are in the habit of acting without reflection but with a sure instinct. Theoretical instruction is therefore waste of time. Even the demonstration of the simplest situation on a sand table is beyond the scope of their understanding. Almost everything has to be demonstrated by actual practice.

h. During their free time the Arabs like to engage in competitive sports. They also enjoy choral singing. They listen attentively to their storytellers and often reveal a keen sense of humor in the comments they make.

i. Religious Arabs observe the prescribed times for prayer, the fasting days during the Ramadan period, and abstain from pork and alcohol. Naturally, commanders must respect the observance of these religious precepts.

j. In battle the Moslem units usually fail to stand up to heavy artillery fire, armored attacks and air raids. To a certain extent this weakness can be overcome by combat training. However, even then an unforeseen situation might lead to panic. The Moslem units are best in guerilla warfare or in fighting along a loosely-knit front. They are excellent on night patrols and open flanks, and in ranger-type combat.

k. If sufficient time is available to give the Arabs thorough combat training, and if teamwork with heavy weapons during both the attack and defense has been well rehearsed, the native units can be used in large-scale operations.

PART TWO

by General der Artillerie Walter Warlimont

I. GERMAN STRATEGIC PLANS FOR TED MIDDLE EAST--1940

1. The Mission to Tabriz. The political entanglement of the European powers resulting

from the outbreak of World War II and, to a lesser extent, the tensions produced by the Russo-Finnish Winter War, led the German Wehrmacht to turn its attention to the Middle East in December 1939. Fearing that the French Army under Weygand might, with British assistance, march out of Syria to threaten or stop the flow of oil from Baku to Germany, the Wehrmacht High Command (OKW) made several attempts to direct Soviet Russia's territorial aspirations away from the Balkans and toward the Middle East.

With this problem in mind, the Operations Staff of the Wehrmacht High Command (OKW/WPSt) in late February or early March 1940 directed German counterintelligence agencies to explore the possibilities of the French sending an expedition toward Baku. Captain Paul Leverkuehn, a counterintelligence officer attached to the German consulate in Tabriz, Iran, set out to survey the area. He had instructions to make a thorough study of the terrain, with emphasis on its value as a route of approach for a French expedition.[1]

[1 - Paul Leverkuehn, German Military Intelligence. London. 1954, p. 3, ff.]

In view of OKW's complete ignorance regarding French strength and equipment in Syria the assignment of only one officer, reveals the utterly inadequate foundation upon which

subsequent Wehrmacht activities in those areas was based. A measure of the inadequacy of this preliminary work was the failure of the OKW to include the establishment of liaison with Arab tribes as one of the steps to be taken by intelligence personnel.

2. England or the Middle East? The Middle East did not really enter into the sphere of German high level strategy until summer 1940. Then, aware that Operation SEA LION might not prove feasible, Hitler ordered the Division for National Defense (Section L) of the OKW/WFSt to make a study of possible alternate military measures against England.[2] Within the limits of this assignment special attention was to be given to ways and means of supporting Italian operations against Egypt, and to measures which might be taken in Syria and "against the Arab countries.”[3]

[2 - The division had suggested a similar study earlier. See MS # C-065e, 4, 5. Manuscripts C-065s-m constitute the so-called GREINER SERIES - OKW/WAR DIARY (1939-43), by Ministerialrat im OKW Dr. Helmuth Greiner, in 13 Parts. Available in English at Historical Division, Hq, U3AREUR, APO 164.]

[3 - MS # C-065j, pp. 3, 4.]

German support of Italian operations in Egypt was no doubt considered primarily as a matter of lending military support to the Italian troops fighting against the British Army of the Middle East[4]. This was certainly true later on. Nevertheless, there can be little doubt that German and Italian strategists were counting on Arab support against the British hegemony over Egypt by members of the "Free Egypt Movement." Expectations of this kind, indeed, went far beyond the borders of Egypt. This is clearly shown by the conversation between Marshal Badoglio and the German General von Pohl on 9 October 1940. Badoglio, on that occasion, is reported to have expressed the conviction that Palestine and Syria would fall of their own accord after the Italians got to the Nile

delta and the Suez Canal.[4]

[4 - MS # C-065e, p. 10.]

In carrying further the idea of waging war against England through measures carried out in Arab countries, Section L on 8 August 1940 addressed a request to the Foreign Affairs Section of the OKW calling for an inquiry to determine "at what points of the British Empire promising attacks might be directed." It is by no means certain that these words, recorded in notes for the war diary of Section L, were actually used in the request; on the other hand, there can be little doubt that the "attacks" were not attacks in the normal military sense of the word, because Germany did not have the means for any such attacks. Moreover, Section L would not have channeled its request for decisions and plans of strategic or tactical nature through the Foreign Affairs Section. It is precisely this fact, that the request was sent to the Foreign Affairs Section, which proves that all further considerations' end plans for action in Arab countries were to be based on political considerations.

Starting from considerations of this nature, Germany had to try and exploit opposition to British hegemony through the prestige Germany had gained by her victories in Europe. All the means of waging modern warfare, such as radio propaganda, money, sabotage, and above all, the shipment of arms, had been invoked, until native opposition burst into open revolt.[5]

[5 - Both the form and content cf Section L's Request to the Foreign Affairs Section, confirm the author's recollection of the German l.ilitary Leaders vague purpose in the Field of Broader Strategy.]

3. Indecision. On 10 August 1940, Section L sent a communication to the chief of the Wehrmacht operations staff, dealing fully with the possibilities of supporting the Italians in their attack against Egypt. The inquiry regarding the possible extension of the war against England, in the event Operation SEA LION were dropped, was dealt with in General Jodl's situation report of 13 August. In this report Jodl suggested to Hitler that England could be brought to her knees in some other way, and that this might be accomplished in the Middle East by taking Egypt, "if necessary with German help." Other Arab countries were not considered in this connection.

[6 – MS # C-065e, p,5 ff.]

[7 – OKW/1848]

It has not been possible to learn whether the Foreign Affairs Section answered Section Ifs request of August 8th. Nor is any information available concerning whether in the succeeding months measures of one kind or another were taken against England in Arab countries dependent on England. On the basis of subsequent developments, this must be considered extremely unlikely.

There are several reasons why Section Ifs suggestions were apparently not acted upon. To begin with it may be assumed that even at that early date Hitler’s own idea of "bringing England to her knees" by indirect means, namely through a preventive war against Soviet Russia, cancelled his interest in the possibility of achieving the same end through action in the more distant Middle East. This trend of thought was no doubt encouraged by a meeting between Ribbentrop and Count Ciano, which took place a few days after Italy's entry into the war in mid-June 1940. At this meeting it was agreed, and sc noted on a map, that North Africa to the latitude of Lake Chad and the Arab lands should be an area within which Italian interests would have priority. [8] This claim to Italian hegemony both in the Mediterranean area and the "Near East11 was also stressed in a report from the German attache in Rome about that time. [9]

[8 – Report of Ambassador von Rintelen, formerly on Ribbentrop’s staff, May 1955.]

[9 - MS # C-O65j, p. 61.]

It is also possible that opportunities of exploiting the Arab nationalist movements were allowed to slip by because of German plans for military collaboration with France. Such a development would have to take into consideration French possessions and colonial interests in North Africa and the Middle East. Collaboration with France, however, contained the pitfall which Hitler had sought to avoid at the time of the armistice with France in June 1940. Namely, that North Africa would escape from the control of Vichy France and be seized by de Gaulle on behalf of the Allied coalition. The Germans, nevertheless, were relying on the French to defend French North Africa. [10]

[10 - Op. Cit. pp. 202, 203, 219, 220.]

Finally, any preparations for the employment of special war measures in Arab countries, which may have teen taken at the instigation of Section L by the competent agencies of the OKW, [11], required considerable time to be put into effect.

[11 - For propaganda, the Press and Propaganda Section; for sabotage, foreign Military Intelligence Section; for arms shipments, Office of War Economy and Armaments; all in combination with the Foreign Office.]

If, on the other hand, the Foreign Affairs Section used Section L's request merely for the purpose of carrying on negotiations with the Foreign Office, Section L was a long

time waiting for a reply. A German Government's declaration of 5 December 1940, addressed to Arab countries, could not be used as a basis for military ventures even at that date. In its political aspects it did not go beyond assurances of friendship for the Arab countries, assurances which in the opinion of the author were limited out of consideration for Italy, perhaps also for Prance, and by an endeavor to bridge differences of opinion within Germany itself. The effect of the declaration was further weakened on 8 December, when the British offensive in the western Egyptian desert resulted in a rapid and complete defeat for the Italians and in direct consequence threatened the very existence of Italy's North African possessions. [12]

[12 - MS # C-065f, p. 3, ff]

This first great military catastrophe for the Axis powers appeared to scuttle every foundation for German plans in regard to Egypt and the Middle East. It was surely not a

coincidence that Spain on 8 December cancelled plans to take Gibraltar, [13] thereby closing the door to possible German influence in Arab territory in North Africa. The extent to which the British dominated the Middle East was clear; they continued to expand and strengthen their position in the Middle East in all directions. [14]

[13 - MS # C-065h, pp. 18, 19.]

[14 - MS # C-065k, p. 12.]

II. GERMAN ATTEMPTS TO INFLUENCE ARAB NATIONALIST MOVEMENTS BETWEEN JANUARY AND MAY 1941

1. Situation Review. Concurrent with Hitler's decisions relative to dispatching an expeditionary corps to Italian North Africa in January 1941, new efforts were made to exploit anti-British trends in the Middle East. The Italian defeat was no longer considered as having put an end to previous plans in that direction; on the contrary, German plans had thereby been rid of obstructing Italian aspirations. Germany was now prepared to enter into direct political negotiations with the dominating elements in the Arab countries, aiming at military undertakings. The main objective remained unchanged—to tie down British forces in the eastern Mediterranean area and to disrupt British lines of communication in the Middle East, Even though at that time Germany was able only to undertake operations of a guerilla nature, the strategic possibilities for larger operations were improving with Rommel's successes and the advanced state of preparations for the Russian campaign.

2. Political Measures. The preceding paragraphs contain the substance of propositions made by General Warlimont at the time he was chief of Section L. They were addressed to General Jodl on 18 January 1941 and had been preceded by correspondence on the subject. [15] The chief of the Foreign Affairs Section approved the propositions at once. He added that the specialists in his section had also approved, and that the military aspects were being looked into. On 29 January 1941 General Jodl stated in writing that the Foreign Offiice believed that further execution of these plans would not be opposed by Mussolini. The "Foreign Office was to draw up the necessary political directives and contact the OKW regarding the military aspects. [16]

[15 - 0p. Cit, p. 109.]

[16 - 0p. Cit., p. 141.]

The foregoing indicates that Hitler himself had not given any thought to the resumption of planning for the Middle East. The impression is strengthened "by the subsequent hesitant approach to the problems under consideration. It was not until 15 February that the intelligence branch of the OKW informed Section L that, following a conference with Dr. Grobba [17] the Reich Minister for Foreign Affairs had agreed to the activation of German policy in the Near East with the object of re-establishing contact with Iraq and Saudi Arabia and disturbing the British in the Middle East. [18] The communication also contained some recommendations regarding ways and means to be considered in shipping arms to Iraq. These recommendations indicate that secret shipments of German arms to Iran might have been going on for some time. [19] Ambassador Grobba had suggested that General der Flieger Felmy be sent to the Middle East as military expert. [20]

[17 – I believe he had been compelled to leave Iraq some time previously, in consequence of British intrigue directed against him. Author]

[18 – MS # C-065k, p.220]

[19 – The author has been unable to verify the fact]

[20 – MS # C-065k, p.220]

The views of the Foreign Office offered little encouragement for the expeditious pursuit of military plans. It can hardly be said that they contained a new point of departure, either as political directives or in connection with the military aspects which the Foreign Office had promised to discuss with the OKW. To all appearances the Foreign Office had no definite plans for German intervention in Arab countries, and knew little about the Arab nationalist movements. This view is confirmed by the fact that Ambassador Hentig, according to his own report, [21] was not sent to reconnoiter the political situation in the Arab countries of the Middle East until early 1941. The conclusions contained in his report sound like fundamental revelations over conditions which the military, perhaps prematurely, had long previously accepted as fact. [22]

[21 - Hentig, Report on Syria, Greater Arabia, arid the Situation in Syria, 26 Feb 41, X-411.]

[22 - Compare OKL/5, Orientierunggmappe Mittlerer Osten, p. 9, Die grossarabische Frage, Par. 1, 2.]

In any event, it might have encouraged the OKW/WFSt to have learned from this report that: [23]

"In Egypt a national front has developed which also exists in the Territorial Army. A strong group under the leadership of a very high ranking authority, seeks to establish contact with Germany" (page 1, footnote 26);

"The real Arabian leaders are conscious of the fact …that they must fight for their freedom. They insist to put in line” (page 2, end, of footnote 26, page 140);

"In view of the existing situation </The dominant/ power can only be Germany"

"and that Ambassador Hentig had recommended that a German mission in Syria assume the task of acting"

"as intermediary between the different Arab States… and thus create a powerful movement against England which will {work to our advantage} in the war" (page 5, of footnote 26, page 140).

[23 – Ed. note. Quotations were written in English in General Warlimont’s manuscript]

The OKW/WFSt, however, knew nothing of these and other statements contained in the report. Moreover, the Hentig Report doesn’t appear to have been well founded In all its parts, so that the skeptical remark made by the Italian ambassador in Ankara, quoted by Hentig in his introduction,---"Is there an Arab movement for independence?"—cannot be dismissed as unjustified. At least that is the only way to explain how Ambassador Rahn, in his own report a few months later, could state that "after a short stay in Syria I learned to my great surprise that there was no Arab movement there", and that "the authority of the German name was almost unlimited. The people were willing to cooperate in everything short of war." [24]

[24 - See Rahn, "Report of the German mission in Syria", 9 May-11 July 1941, X-410, pp. 26, 28.]

This uncertainty in the political sphere hindered the development of a stronger Arab policy on the part of Germany, and explains in great part why a more active German policy was not initiated until the second half of April 1941, at the time of the Iraq revolt.

3. Military action.

a. Before the Iraq revolt. She inadequacy of German political preparation may have contributed to the fact that the OKW had apparently found only a very few ways prior to the Iraq revolt to exploit the Arab nationalist movements along the lines repeatedly suggested by Section L. Moreover, it appears that the German intelligence service was so inadequate that it failed to recognize the signs of unrest which led to the Iraq revolt. [25]

[25 - See General Felmy's study, Part One, above.]

Among the few measures actually carried out it is highly probable that arms and ammunition were delivered to Arab countries other than Iran and Palestine. The size of these shipments cannot have been very impressive, if only because Great Britain controlled all sea and communication routes to Arab ports. [26]

[26 - This negative impression is endorsed by former members of the OKW’s ordnance supply office, who declare either that they cannot recall any such shipments being made or that no such shipments were known to them at that time. No weapons were delivered to Saudi Arabia in the course of the war. Ambassador designate Khalid al-Hud in 1940 obtained Hitler's promise of several thousand infantry rifles with ammunition. He also made some efforts to place an order for additional infantry rifles with German industries. The order, if placed, was not filled.]