Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

MUTINY ON STOROZHEVOY

A Case Study of Dissent in the Soviet Navy

by Gregory D. Young

|

Storozhevoy's rush across Baltic Sea into the Swedish territorial waters on November 9, 1975. Storozhevoy is on the left, sea border patrol ship on the foregrounbd, Ty-160 airplane is simulating bombing run on Storozhevoy. (Images and descriptions by AWW).

Abstract

In November 1975, a group of sailors led by the ship's political officer took over the Soviet "Krivak" class destroyer "Storozhevoy" and attempted to sail to Sweden to seek asylum. They were attacked and turned back by Soviet naval and air units. Information of this dramatic event which has never been acknowledged by the Soviets, made it to the West only piece by piece. It was the intent of this study to assemble all available data for critical analysis to determine potential causes and implications.

This mutiny is not the only instance of dissent in the Soviet Navy r.cr will it be the last. Problems of alcoholism, officer-enlisted relations, food, hazing, habitability, desertion, ethnic friction and unhappiness over constant political indoctrination appear to be widespread.

The key question is: how important, are these instances of dissent and how do we incorporate them into a framework for assessing soviet military capability and performance?

In the past we have overemphasized quantitative aspects of assessing military and naval power. The factors which are less quantifiable such as "fighting spirit", unit cohesion, and morale have made a greater difference historically. In the allocation of scarce resources for defense and other national priorities, it is essential to make intuitive estimates of potential enemy capabilities, as accurately as possible. In the case of the Soviet Navy, even planning for the worst case, it seems defense planners still have overestimated some of their strengths. The Soviet Navy has grown from a coastal defense force to a blue-water fleet capable of greater influence on the seas. They are not, however, ’’ten feet tall" as is emphasized currently in much of the literature.

I. INTRODUCTION

How is military power measured? In the West, generally, attempts to measure are done by numerically tabulating forces of various sorts: the numbers of men under arms, the number of weapons of a given type, etc. This is itself an evasion of the problem of estimating the more significant factors of military power, since it says nothing about the actual capabilities of the forces of one country to deal with another. These numerical counts of men and weapons do not include geographical constraints, natural resources, potential military capability and most importantly, the command style and will or fighting spirit of the soldiers or sailors of the respective nations. If one looks at battles in history, people and their nonquantifiable capabilities have been more important in battle than numbers or equipment capability. In World War II, German General Erich von Manstein was willing to accept an adverse one-to-nine ratio in division units when fighting the Soviets on the Eastern Front. He knew his forces were that much better.

This case study will focus on one dramatic incident which occurred in the Soviet Baltic Fleet. The author, in final analysis, will attempt to show that the Soviet Navy is not as overpowering as the numbers of ships and similar quantifiable factors would indicate. The ships may be bristling with armament above decks while dissent is brewing below decks.

This study attempts to assemble the facts about the mutiny and discuss the important aftermath for the crew and the vessel. The Soviet reaction or evidence of the reaction will be investigated through a number of Soviet public pronouncements. This study will cite a number of causes which could have led to the mutiny. In addition, it will examine causes and effects of morale problems in general in the Soviet Armed Forces and specifically the Soviet Navy.

To assess the implications of this event and morale problems, one must focus on how military power and combat capability are most commonly measured. One must then generate an intuitive framework to include human factors in some sort of capability measure. This study, therefore, points to the conclusion that since the navy of the Soviet Union has extended itself to an active position in all the oceans and seas of the world, the personnel problems which may have been thought to be insignificant have been exacerbated and brought to the forefront. The Soviet Naval High Command has to realize that some scarce resources are going to have to be spent to improve morale, because Soviet weaknesses are becoming evident to the West. The Western military planners are beginning to realize that personnel problems may be the most important Soviet vulnerability that can be exploited.

II. DATA SOURCES

Assembling a study such as this is not without difficulties. Getting information out of the Soviet Union on military matters is always difficult and even more so about an event such as a mutiny. The Soviets have made a deliberate attempt to keep the mutiny a secret.

The research is based solely on secondary sources: either interviews by the author or press accounts of the mutiny. The author also interviewed two journalists who had researched the event and received a great deal of analysis and speculation from sources', considered to be experts in Soviet Naval Affairs. As is the case with dramatic acts of violence whose accounts are prone to exaggeration, there was a great deal of conflicting data. The author many times had to choose one source over another as being more valid. Speculation, which is noted as such in the paper, was used to fill in the gaps between facts. The study presents the first compilation of facts, speculation, and analysis about an event which is important to Western military planners.

The author placed advertisements in three U.S. based émigré newspapers. They were Novoye Russkoye Slovo, Russian Life Daily and Laiks (the Latvian emigre' newspaper). The advertisement stated: "Graduate scholar looking for persons who have served in the Soviet Navy since 197 0 or those persons who have any knowledge concerning the mutiny that occurred aboard a naval vessel in Riga in 1975." Five persons responded to the advertisement. Four chose to remain anonymous. The five are numbered 106 through 110 in the list of references. All were interviewed over the telephone; each interview taking at least an hour. The author has no knowledge about the reliability of the telephone interviewee’s information and if the respondents are in fact who they claim they are except that their information was confirmed by other research. This author understands the problem of using information from emigre'* sources; that is using sources who have left the Soviet Union and are emotionally biased against the Soviet regime.

In this case and in connection with general morale in the Soviet Navy, the author attempted to separate the facts from opinion.

Three human sources were particularly important to this research. Each had done some investigation into the mutiny on the Storozhevoy, but had not assembled enough information on his own. These people - Alex Milits, a Swedish journalist, Mikhail Bernstam, a Soviet dissident now at the Hoover Institution and David Satter, the Moscow correspondent for the London-based Financial Times - provided essential data.

The compilation of information from these three sources, as well as the author's research, provided the facts necessary for an accurate evaluation of the mutiny.

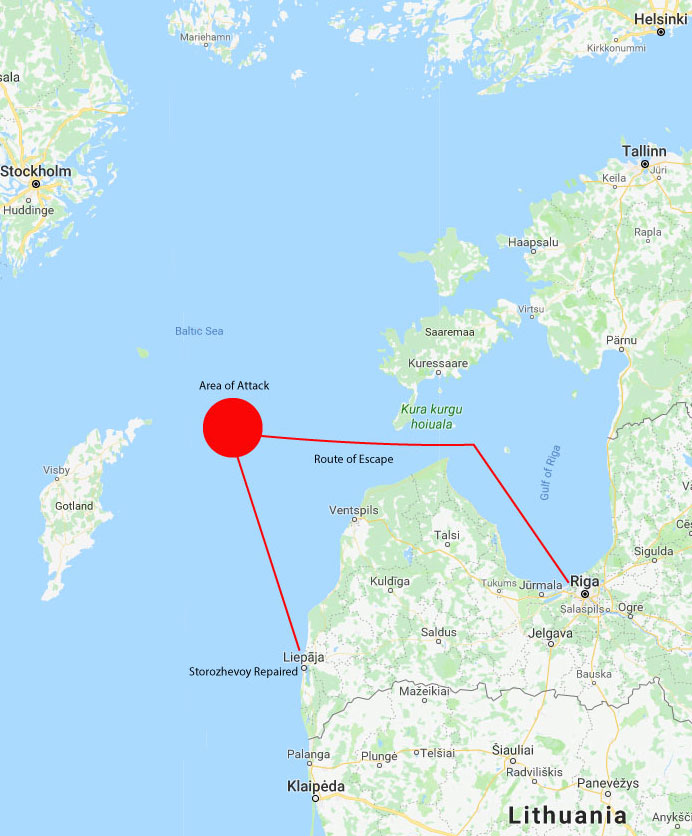

III. PRELUDE

On the seventh of November 1975, the 58th anniversary of the Russian Revolution was being celebrated throughout the Soviet Union. To join in the celebration in the port city of Riga, capitol of the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic, the destroyer “Storozhevoy” of the "Krivak” class had moved from its homeport of Bolderia to a pier in Riga 15 kilometers up the Daugava River. She was moored on the east banks of the Daugava (the Russian, rather than Latvian name, is Zapadnaya Dvina) at the customs pier. This area is near the center of this city of 650,000 people, near governmental buildings and near the narrow winding street of “old Riga.” The ship had been open for tours by local citizens all day (see map). Approximately one half of the Storozhevoy's crew of 250 men had been given shore leave to join in the anniversary festivities.

Storozhevoy at sea.

The Storozhevoy was one of then fifty-seven major surface combatants in the Soviet “Twice Honored Red Banner Baltic Fleet.” Bolderia was smaller than the major fleet bases at Leningrad, Kaliningrad (Fleet Headquarters), Liyepaya and Talinn, but still supported a few destroyers, escorts, and diesel submarines [65].

The Krivak class first appeared in 1970, a product of the Baltysk shipyard near Kaliningrad. With 400 feet of length and 3800 tons displacement, the Storozhevoy and her sister ships are handsome ships designed for both speed and seakeeping. Eight sets of gas turbines provide her with 112,000 pounds of shaft horsepower. An impressive assortment of armaments lines the decks- She has two twin 76»:m guns eft, two twin 30mm guns and two quadmount torpedo launchers amidships. For air defense, the Krivak class has two SAN-4 surface-to-air missile launchers. Up front, she displays a quadlauncher for the SSN-14 anti-submarime warfare (ASW) rocket-assisted depth bomb [53:155]. (See photo and diagram Appendix D). The Soviets referred to the Krivak class as a "large ASW ship" (Bolshoi Protivolodocny Korabl) in 1975, but in 1977 redesignated it a patrol ship [31:113]. The Storozhevoy was one of six Krivaks in the Baltic fleet in 197 5. The class now numbers twenty-six and more are still being built.

The Zampolit (political officer) of the Storozhevoy, a Captain Third Rank (Lieuteuant Commander) by the name of Valery Mikhaylovich Sablin, had stayed aboard ship rather than venture into Riga with a number of his fellow officers. He had a great deal of planning to do.

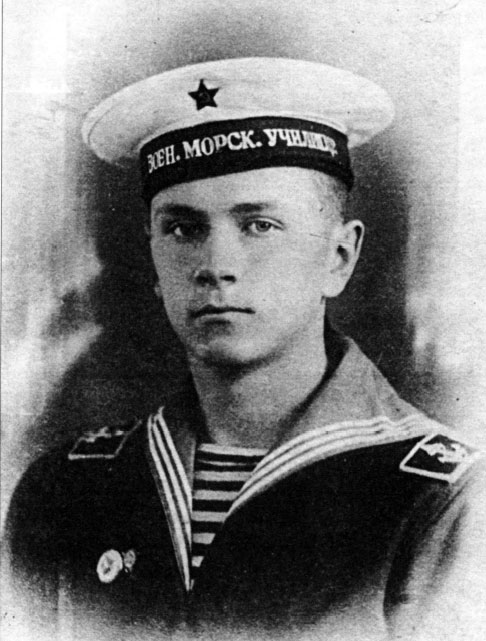

V. Sablin as a Soviet Navy cadet in September 1956.

The job of Zampolit is a descendant of the Pre-World War II political commissar. He is no longer of equal rank to the ship's commanding officer but is subordinate to him. He does, however, have a completely separate chain-of-command within the military political directorate (GLAVPUR) headed by General Yepishev. Much has been done to improve the traditional reputation of the Zampolit as the shipboard "informer." He now functions like a combined personnel officer, chaplain, and welfare and recreation officer in addition to removing the majority of the burden of political education from the other officers [48:20].

The old political commissars were drawn from the civilian populace directly and thus did not mesh well with the other members of the shipboard wardroom. The Zampolit of today on the other hand is frequently recruited from armed forces personnel who have shown promise as Communist Purty activists. At a special school in Kiev, the prospective political officer not only receives extensive schooling for his primary mission of political enlightenment, but is also trained to fulfill a military function in his future unit as well. In a major combatant ship like Storozhevoy, the Zampolit is the third in command following the CO and his senior assistant (Starpom) and is required to qualify as an underway watch officer [48:20].

The Zampolit thus sits in the unique position of being the one person to whom all sailors are encouraged to take their welfare problems, like an ombudsman, but still can command the ship and extract respect from the sailors. If he is sensitive to their problems and not just a "party hack" or informer, he is the one officer who could establish some sort of rapport with the sailors.

Other junior officers may have an interest in their sub-ordinates- but do not have time to develop this interest due to other responsibilities. Junior officers are not only the shipboard managers and military leaders but also the main technical specialists of their respective departments. They must supervise and often perform the major maintenance and repair functions. They still carry some burden of political work; they are the backbone of "socialist” competitions and fulfill their own responsibilities as candidate party members. Fully 80% of all Soviet officers are party or Komsomol members [11:114]. The Navy figure is 95% [22:54].

V. Sablin taking classes in Military-Political Academy.

It is evident that Sablin, despite his upperclass upbringing, was able to establish a special rapport with the enlisted sailors. He was the son of a Soviet Colonel and had grown up a privileged member of Soviet society [99], Sablin was born in Gorky in 1935. He was a descendant of the Decembrist N. S. Bestuzhev, who took part in the 1825 revolt against Czar Nicolas the First [60].

The twice weekly, two-hour political lessons of Marxist- Leninist theories aboard the Storozhevoy must have degenerated into the mere monotone reading of Pravda editorials, which the sailors looked upon as incursions into their very little free time. This was followed by the ratings expressing their dissatisfaction with food, living conditions, extra duties, limited leave and other usual sailor complaints. The unusual thing was that Sablin probably agreed with them rather than exhort the standard party line. One such meeting was taking place with those remaining onboard the ship that afternoon in November 1975 [99],

The Storozhevoy had been very busy since its commissioning in early 1974. On the third of October 1974 the Soviet newspaper Izvestiya reported the arrival of a three ship Soviet Naval contingent in Rostock, German Democratic Republic (East Germany) for a five-day visit. The Storozhevoy, the cruiser Sverdlov, and the destroyer Obraztsvoy were there to join in the celebration of the East German twenty-fifth anniversary. Vice Admiral V.V. Mikhaylin, Commander of the Baltic Fleet, led the group [82:2].

The Soviet. Minister of Defense, Marshal Grechko, sailed onboard and "evaluated" highly the mastery of the antisubmariners in their firing of ASW missiles (either SSN-14 or RBU). He stated that the Storozhevoy "had all the requirements necessary to win first place in Socialist competition among outstanding ships." [35:211] This show must have been a "Potemkin Village" put on for the Defense Minister because on the 24th of December 197 4 an article appeared at the top of page two of the Soviet military newspaper Krasnaya Zvesda (Red Star) which was very critical of the Storozhevoy by name. It cited the Grechko visit and went on to say that Storozhevoy had finished the training year in October 1974 very poorly. The article criticized the discipline onboard and some "comrades" were accused of lapses on "the ethical" front and "taking up the liberal position in the fight for purity of the heart." [62] This jargon is usually translated to mean the officers were not very good at maintaining discipline and moreover were not particularly interested in being good party members.

The article compares the two gun batteries of Senior Lieutenants Dubov and Kolomnikov, saying that the subdivision of the former was always successful in competition where the latter lagged continuously behind. Kolomnikov was excused due to his youth and inexperience and lack of guidance he was given by the Communist Party organization of the ship.

The article went further to criticize the party organization on the ship mentioning party members Firsov, Sazhin, Potulny and finally Sablin for their inability to explain the ship's problems. The news account ended with the standard exhortation to do better and for the communists to "carry their party cards next to their hearts." [62] (See Appendix A for entire text of the Krasnaya Zvesda article.)

Only six days prior to this article the Storozhevoy had been mentioned in a positive light in another Krasnaya Zvesda article. She had participated in a coordinated ASW exercise with aircraft and submarines. The article praised the tactical competency of the commanding officer and praised the subunits of Captain Lieutenant Ivanov and Senior Lieutenant Vinogradov for "seizing the combat initiative." They were given an outstanding grade [86:2]. It is unknown if this is the same exercise that was discussed six days later. A later article in Krasnaya Zvesda in early 197 5 related another successful ASW exercise by the Storozhevoy but gave no indications that the ship had overcome her problems or would be classed with other outstanding ships [35:212].

The Storozhevoy had spent a great deal of 197 5 at sea underway. Most notable was her participation in the "Okean" exercise of 16-27 April 1975. The Storozhevoy was one of 220 ships that participated. It joined in the Soviet show of force in the Atlantic and thus spent a good deal of time away from its Baltic homeport. In the December 197S issue of the West German journal Marine Runschau, the Storozhevoy was cited as a participant in a Baltic live missile exercise which included seven cruisers, two other destroyers and a number of OSA class patrol boats. The exercise took place in mid- October 1975.

At the shipboard meeting of certain crew members that afternoon of November 7, 197 5, those Petty Officers and conscripts whom Sablin had been selecting and molding for months must have joined him in a crucial decision. They would lock the other officers in their cabins below decks that night and would sail to the Swedish island of Gotland and seek political asylum. At an average speed of 33 knots the journey of 17S nautical miles through the Irben Sound from Riga to freedom could take no more than five and one-half hours.

Sablin was counting on the fact that the holiday would give then a head start. In addition, they counted on the other officers sleeping more soundly than usual due to their celebrating during most of the last two days [80:15].

IV. THE MUTINY

At approximately 0200 hours on the eighth of November, the Storozhevoy slipped quietly from her berth in Riga to begin a dash across Riga Gulf. Course was set for the Irben Channel at the mouth of the Gulf between the Osel and the Courland Peninsula. It will probably never be known how many of the crew were loyal to Sablin and the other conspirators. Although gas turbine powered, the Krivak class is considerably less automated than the later American gas turbine powered "Spruance" class and would thus require a greater number of persons to man the engine room and the bridge. In addition, line handlers and persons in navigation and auxiliary spaces would be required. It would be possible to speculate that Sablin with one other known officer participant named Markov and a loyal following of a dozen petty officers, were able to order the remaining skeleton crew of unwary 18 and 19-year-old conscripted sailors into manning their respective stations with tales of a national or naval emergency.

Able seaman Shein helped Sablin to take control of the ship, was executed together with Sablin.

Storozhevoy means "watchful" or "on guard" and the ship and crew were being just that. The mutineers were sailing, with lights out at 30 knots which is still short of the vessel's maximum speed. They were consciously avoiding other ships in the gulf.

Available evidence is not completely clear on how the alarm as actually sounded or what convinced the Baltic authorities that a mutiny was in progress. The harbormaster reported the ship's departure probably within about 3J minutes in accordance with standard regulations.

A single conscript not loyal to Sablin's cause jumped, overboard. before the ship reached the mouth of the Daugava River and the Gulf of Riga. This man caught his breath by clinging to a channel marker buoy before swimming to the west bank of the river. His attempt to inform Soviet authorities of the mutiny in progress was reported by two different accounts in the Soviet underground press, the Samizdat [111:2].

The sailor, cold and wet from his swim, first tried to flag down the few cars running at 3 A.M. No one stopped assuming he was just another sailor drunk from over-celebrating the holiday. Public transportation was not running due to the holiday. The young conscript finally reached a public phone and called the duty officer at the Bolderia Naval Base outside of Riga [104]. The sailor said he had something very important to say that he could not disclose over the phone. He asked the duty officer to send a car to pick him up. The duty officer refused again fearing another drunken sailor in the midst of a telephone prank. The sailor ended up making the distance to the Naval Headquarters on foot, thus giving the Storozhevoy a little over a two-hour head start [111:2]. Disbelievers at the Riga Naval Headquarters attempted contact but received only silence in return. Still there was no vigorous reaction by Rear Admiral I.I. Verenkin, Commander of Riga Naval area, to call in Moscow. It was only when the amazing message, "Mutiny onboard the Storozhevoy: we are heading for open sea" was received on an emergency frequency, that the Naval High Command and Soviet Defense Council, including Fleet Admiral Gorshkov (Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Navy) were awakened and notified [66:65]. Chaos erupted at Naval Headquarters. The message was evidently sent by an officer who had surreptitiously freed himself and made his way to a radio undetected, although a conspirator who had changed his mind could have sent it. This particular message and all radio traffic that followed were received uncoded and in clear Russian by the Swedish Armed Forces.

Two naval reconnaissance aircraft were ordered off immediately on a locating mission from the Skirotava airfield on the Southeastern outskirts of Riga. Nine other Baltic fleet ships were also dispatched in the chase including another of the Krivak class, and a patrol boat from Riga [80].

Yak-28 reconnaissance airplane, which was used to find and shadow Storozhevoy.

Four hours had elapsed since their departure from Riga. Storozhevoy’s new leaders were optimistic; the previous radio contact and the conscript who had jumped overboard were unknown to them. They had passed the Irben Sound and were out of the 12 nautical mile limit of the Soviet territorial waters into the Baltic Sea when the first of the now 10 aircraft in pursuit found them. Half the aircraft were "Bears" from the Soviet Naval Air arm, and half were fighter-bombers from the Soviet Air Force. By all appearances, the pilots had been ordered not to sink the valuable ship if at all possible. From the air the ship was ordered to "lie dead in the watei" and promises of non-punishment and pardons for their crimes if they would return to the Soviet Union were given over the radio, but Storozhevoy did not alter course or respond [52:13].

The order was given to attack, but some planes sent to quell the mutiny initially refused. The Swedes recorded "very stormy conversations" which revealed reluctance by the pilots to bomb their naval comrades. The planes eventually carried out the order, except for one who declined to take pass and returned to base still carrying his ordnance [78].

The first shots were fired across the bow and then bombs were dropped to a circle still trying to avoid damaging the destroyer. No response came from the Storozhevoy. It remains unclear to this author whether it lacked the men and knowledge to man the anti-aircraft weapons, or the crew simply chose not to do so, feeling that to return the fire would be suicide. One source said that all the ammunition was secured and thus those involved in the rebellion were unable to get to it. Another source stated that Sablin gave orders that "no one was to suffer at their hands", [111:3] He did not want them to commit any violence in their quest to escape.

Evidence of the utter chaos and disarray is clear. As the Storozhevoy began evasive maneuvers to avoid the attacking aircraft, the pursuing Naval Forces closed the gap. The lead ship in this group, the sister ship of the Krivak class, came under attack by mistake in the early dawn light. Rockets hit on the deck and the bridge area of the pursuing ship. In the aftermath, this ship received more damage than the Storozhevoy. This ship was seen by many Latvian sources being repaired in Riga immediately following the incident [75:2].

Rocket ship, participating in the attack and firing at the pursuing ship by mistake.

On board the Storozhevoy the rudder had been hit making control difficult. Certainly, by now those conscripts who had been unaware that a mutiny had occurred aboard were aware something was amiss. Also, borderline conspirators must have felt now that they had no chance of success at this point, Sablin and the few remaining zealots no longer had the numbers necessary to continue;. The mutiny ended meekly and by 0800 the Storozhevoy had surrendered and been boarded by naval men from ships which had reached their position. She lay dead in the water only 30 nautical miles from Gotland [80].

The firs; ships to reach Storozhevoy were not those dispatched from Riga, but patrol ships and escorts which had come from Liyepaya. The boarding parties met no resistance; on the contrary they were met with appropriate salutes and normal military courtesies as if nothing had happened [111:2], Sablin himself was on the bridge. He had received a minor wound in the bombardment. None of the crew members who had been locked up were injured. The Captain's hands were bloodied either from trying to force his way out or from his attempts to signal his predicament to others [104].

Border patrols ship MPK-25, which participated in the pursuit of Storozhevoy.

An emigre' interviewed by this author who was on the staff Krasnaya Zvesda in the Baltic Military District at that time heard through his superiors about the event. He stated that the crew of the Storozhevoy was removed on the spot and taken to Riga. The numbers of billed and wounded vary dramatically in the press, but this same source stated that, his superiors told him that the killed and wounded on the Storozhevoy were "less than fifteen" but thirty-five received the same fate on the accidentally attacked sister ship [108].

Route of Escape and Area of Attack on Storozhevoy.

The Storozhevoy itself was towed to Liyepaya, a Latvian city on the Baltic for repairs. Being a closed city, (Soviet citizens may not even visit there without special permission) Liyepaya provided the Soviets with the necessary security to accomplish the minor repairs in secret [104].

V. Sablin

V. AFTERMATH

Shortly after the drama, a Krivak class destroyer in perfect condition bearing the Storozhevoy's number made a conspicuous cruise along the Soviet Baltic Coast participating in a number of official celebrations in order to quell the rumors and accounts that had begun to emanate front that area [75:2]. It is of course possible that it was another ship where name and number had been switched. The Storozhevoy had appeared with different numbers prior to the mutiny -both 203 and 626. Having different, numbers, which a common, practice in the Soviet Navy at that time, has been stopped lately. Many Western analysts feel that in order to instill more pride in crew members, the Soviets now paint the ship's name prominently on the stern. Changing numbers randomly, therefore, would no longer confuse western intelligence.

On the twelfth of November 197 5, articles in the Swedish press appeared saying that the wreck of a Soviet target ship was found abandoned in Swedish territorial waters off of Gotlund. The Soviets apologized shortly thereafter and re-trieved the hulk -saying it had been used for target practice on the eighth of November in the Baltic and had drifted away.

A fisherman from Gotland was quoted as saying that it did not appear in the waters off Gotlund until the eleventh of November. At this time very few people knew anything about the attempted mutiny. The connection was not made until a few years later that- the Soviets deliberately set the target ship adrift there to provide an explanation to anyone who had monitored the event [104].

On the eleventh of April 1976 with a new crew, Storozhevoy sailed from the Baltic with a Ropoucha class LST and an oiler, passed through the Mediterranean Sea and Suez Canal, entering the Indian Ocean on the twenty-fifth of April [34:208]. The Storozhevoy operated there for two months before transiting first to Vladivostok then on to Petroparlovsk where it is now homeported with the Kamchatka Flotilla of the Soviet Pacific Fleet. Like many Soviet dissidents before, the Storozhevoy was banished to Siberia. It appears that the continued presence of the ship in the Baltic would only fuel the mutiny accounts that were then circulating. The Storozhevoy has been photographed by Japanese reconnaissance aircraft from Okinawa wearing a distinguished citation award that had not been present before the mutiny. It is not known if the citation award is a result of the mutiny. "Dentology" of these photos revealed no trace of any damage from the attack. The number was again changed and in 1980 Storozhevoy bore the number 682 [103].

The fate of the conspirators and the rest of the crew is not nearly so clear. Military discipline in the Soviet Navy is much more stringent than in the U.S. Naval Service. Great stress is put on "exactingness" which means a detailed devotion to all military rules and regulations. In the case of mutiny, however, U.S. and Soviet Naval regulations parallel--the death penalty is prescribed.

In general, one facet of Soviet military justice, to ensure compliance with regulations, is to make an example of offenders. When a Soviet sailor is inducted, he recites a military oath of strict obedience and states that should he break his vow, he should be subject "to the severe punishment of Soviet law and the general hatred and contempt of the workers." [42:52] To see that this hatred comes about, Soviet, military journals and newspapers often run stories of malefactors complete with actual names and units. It is assumed that such public humiliation will induce the guilty person to see his errors and prevent others from similar conduct. In the case of the Storozhevoy, the potential for national humiliation or evidence of military weakness overrode the need to make an example of the conspirators. The mutiny, the resulting trial, and punishment have been kept a fairly well- guarded secret.

On the morning of the ninth of November, Sablin and some of his co-conspirators appealed before the procurator (prosecutor) of the Court of the Baltic Military District in Riga as required by Soviet law. Due to the nature and severity of the crime they were flown to Moscow later that day and interned at the GAPTVAK (short-term military prison) of the Moscow Military District [99].

The Chief procurator from Moscow, Anatoli Rudenko, arrived within a week to lead the investigation [74]. Initially the investigation consisted of routine discussions at all levels of the Baltic Fleet by commanders, political officers and representatives of Yepishev's political staff from Moscow. Once this was complete however, the order was issued that no information or any responses concerning the mutiny would be released. All discussion was to cease. Not even closed letters from one local party central committee to another would mention the Storozhevoy's attempt to flee [111:3].

The trial of 15 of the mutineers, including Sablin, took place in May of 1976 before the Military Division of the Supreme Court of the USSR [99]. Because of the nature of the crime and the potential for capital punishment the two lower courts, the Military Tribunal of the Baltic Fleet and the Military Tribunal of the Navy, were bypassed. Under normal circumstances less severe crimes committed by Communist party members or political officers are tried outside the military system by Party Commissioners at each level [17:155].

Captain Third Rank V. M. Sablin was given the death penalty and the sentence was carried out by a firing squad soon after the 3-day trial. On the eve of the execution, Sablin's father was granted a twenty minute meeting with his son. The meeting took place in the presence of a large group of KGB officials. Sablin and his father were permitted to talk on "personal themes". [60] The account of this meeting was published by the Soviet underground.

Sablin's family did not escape the wrath of the Soviet regime. One of his brothers, who worked on the General Staff, was transferred to eastern Siberia. Another, who was a teacher in an institution in Moscow, was moved east to Ivanovo [60].

The second mutinous officer was sentenced to 15 years in a labor camp. The fate of the enlisted conspirators is unknown, but one less reliable source stated that overall 82 crew members were executed [68]. This very high figure is possible due to the fact that no primary source for the mutiny has come forward in the following six years and that the suppression of information concerning the mutineers has been so successful. This author is still inclined to believe the number executed was considerably less because far more sources have testified to fewer resulting deaths. The remainder of the crew, including the Captain, were dispersed to various locations throughout the Soviet Navy. Underground sources stated that even these officers who did not participate in the mutiny were reduced in rank by one grade [111:3].

VI. REACTIONS

A. SOVIET REACTIONS

The Soviet government has yet to admit that a mutiny ever took place aboard the Storozhevoy, and it is doubtful at this point that it ever will. The only official pronouncement on the mutiny, a denial, was made by Vice Admiral V. V, Sidorov, First Deputy Commander of the Baltic Fleet, at a press conference on 10 August 1976 in Copenhagen, Denmark. The Admiral was there commanding a five-day diplomatic port call of two older Soviet naval vessels; a Kotlin class destroyer "Nastoychivy" and a Mirka class Corvette. Sidorov in reply to the question of mutiny stated:

Mutiny on a Soviet Naval Ship in the Baltic--unthinkable! It must be a hoax played by organs established for this purpose which pursue their thwarting aims in the West. Stories of that sort, which appear in the Western world, can only invite ridicule among us. We do not believe we even have to comment on that sort of thing [89].

Despite not admitting to the mutiny explicitly, the Soviets have, by the change in the content of certain public pronouncements, all but acknowledge it occurred. Soviet Communist Party Secretary General Brezhnev at the 25th Party Congress in February 1976 discussed military leadership specifically in sophisticated terms. Military leadership had not been mentioned by Brezhnev in his address to the 24th Congress nor was it mentioned at his most recent speech before the 26th Congress. He pointed out that:

The modern leader must combine within himself the party-mindedness and profound competence, discipline , and initiative, and he must take a creative approach to matters. At the same time, on any issue the leader is obligated to take account of the sociopolitical and educational aspects, to be tactful toward people and their needs and aspirations, and to set an example at work and in his daily life [34:211].

Admiral Gorshkov referred to these comments in his Navy Day interview, "these high party demands apply in full to commanders of ships, units and formations." These words suggest that the time has come in the Soviet Armed Forces, and the Navy in particular, when a commander must understand and relate to his men and not just follow orders and perform "by the book” as has been traditionally preached.

In an article in Krasnaya Zvesda on 11 February 1976, Gorshkov discussed shortcomings in the work of some Party organizations in the Soviet Fleets and criticized the level of efficiency attained by engineering officers. He stated:

Ship commanders and Party organizations had to pay particular attention to the ideological education of junior officers. We must study in greater depth, and seek to influence the formation of the ideological and moral potential of the future commander's personality, weighing up strictly whether the officer is ready to be a military leader in the era of the scientific-technical revolution, to be genuine innovator, whether he is capable of taking firm, scientifically-based decisions from party and state positions [54:16].

The Admiral, in the past, had very seldom mentioned disci-pline in such specific terms, especially in terms of the "ideological commitment" of some of the officers. Such criticisms were either avoided or left for comment by lesser officials. These comments and many others reflect, the frequently recurring themes in professional Naval writings of discipline or ideological fervor in the time immediately following the mutiny. (Such comments increased after the flight of Victor Belenko in September 1976.)

In the February 197 6 edition of Morskoy Sbornik (the Soviet Naval Digest), Admiral Gorshkov again stressed the importance of command emphasizing discipline. This February issue vould probably be the first one appearing whose content could have been affected due to the mutiny, given the 50-56 days of preparation for each issue (Typesetting and printing dates are given in each issue) [38:335]. This author performed a content analysis of Morskoy Sbornik from the January 1975 issue through the January 1977 issue to determine if the percentage of articles dealing with the topics of political indoctrination, political training or military discipline had increased from the year prior to the mutiny to the year following the mutiny. The January issue was eliminated from the comparison for two reasons. First, since the 25th Communist Party Congress was convening the next month, there was an unusually high number of politically related articles (eight of thirty-five). Second, with minor fluctuations in the printing dates, the January issue could have been writteh either before or after the mutiny. Thus, the comparison of post-mutiny articles began with the February 1976 issue. The resulting analysis shows a 5 percent increase (from 11 percent to 16 percent) in articles dealing with discipline, morale and political indoctrination. Certainly there are myriad other factors which could have influenced this increase of political articles but the fact that there was an increase points towards evidence of the mutiny.

In the research for this study, translations of the Soviet military and civilian press, as well as the Soviet Naval Digest and other military journals, were searched for references to the Storozhevoy. Although this search was certainly not exhaustive, it is still important to note that five articles mentioning this ship were found in the two years prior to the mutiny and none were found in the seven years following the event.

Late in 1978, the Soviet Navy promulgated new shipboard regulations. This was the first major overhaul of these regulations since 1959 although minor revisions occurred in 1967. The new regulations added two new shipboard departments to cope with the advancing technology of the fleet, but more importantly, the regulations increased the role of the com-manding officer in political indoctrination. The revised shipboard regulations "place emphasis on the duties of the commanding officers to direct the work of the political apparatus toward successful accomplishment of tasks assigned to the ship, and to strengthening the military discipline and increasing the political morale of personnel." [26] The new revised regulations place greater responsibility on the ship's commanding officer for the overall direction of political work, including more supervision of the Zampolit. It would seem that the ability of the ship's political officer to be a rival to his commanding officer's authority has been greatly reduced under the new regulations. Commanding officers are expected now to increase readiness and combat capability by supervising a thorough political and ideological indoctrination of their crew, both officers and enlisted men. The new regulations continue to exhort the need for "exactingness" in performance of duties on now longer voyages and thereby develop a more harmonious shipboard "ccllective."

The most dramatic Scviet reaction to the mutiny was the leadership shake-up which occurred in the Baltic Fleet immedi-ately following the incident. Admiral Vladmir Vasilyevich Mikhaylin was relieved as commander of the Baltic Fleet within three weeks of the mutiny [34:209]. He had served that post since 1968 , having served as First Deputy Commander of the Baltic Ileet for the four years prior to that [12:78]. Mikhaylin was moved to Moscow to be Deputy Commander~in-Chief for Naval Educational Establishments. According to William Manthorpe, former U.S. Naval Attache* to the Soviet Union, this job is not befitting a former fleet commander [103]. He had been awarded the Order of the October Revolution on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday in July 1975. Mikhaylin's departure certainly was not in line with the timing of the normal Soviet Navy practice of serving as First Deputy Commander before moving up to Fleet Commander because Mikhaylin’s First Deputy, Vice-Admiral V.V. Sidorov (mentioned earlier), had been on the job only a few months and could not be promoted [4-1:101]. Mikhaylin was therefore replaced by the Baltic Fleet Chief-of-Staff Vice-Admiral Anatoliy Mikhaylovich Kosov, who had served in that capacity since 1972.

The Baltic Fleet Political Directorate Chief escaped the purge. Vice-Admiral Nikolay Ivanovich Shabilikov has served in that position from 197 2 until the present time. The Commander of the Riga Naval Base, Rear Admiral I.I. Verenkin must have been thought to be too new to receive any of the blame. He arrived at that post in May 197 5, six months before the attempted mutiny [41:299].

It would certainly seem that if the blame for ^his event had to be placed anywhere outside of the mutineers, it belonged with the Political Directorates of the Baltic Fleet and of the Navy. The fact that Shabilikov remained in office, given the fact that the mutiny was led by a political officer, sheds an interesting light on the power balance between the political Directorate and the Naval High Command.

B. SWEDISH REACTIONS

The events in Sweden after the mutiny are especially pertinent since a great deal of what is known about the mutiny originated there. The majority of what occurred from the time the Storozhevoy departed the Gulf of Riga until the ship surrendered was monitored by the Swedes on either radio or the radar of Swedish Patrol aircraft. The Swedes did not, however, reveal publicly what they had monitored. The first press account of the mutiny appeared on the 23rd of January 197 6 in the Stockholm Daily, Expressen, and carried the byline of Alex Milits, journalist of Estonion origin living in Sweden. The majority of other news accounts used quotations from this report or from later accounts Milits would write. How he came upon the story and how it later unfolded to some degree are important to mention.

In late November 1975 Milits was visited by a Latvian émigré who had just returned from a visit to Riga. The emigre asked, "Why has no one written anything about the mutiny that occurred in Riga?" The emigre'” then said that six different people had talked about the mutiny while he was in Riga. He had been told that it was a large ship, "possibly a destroyer or cruiser". [104]

Being unwilling to write about such an important event with only one source, Milits visited the port area in Stockholm and inquired among Soviet merchant sailors from various Baltic ports including Riga. Most had not been home for some time and knew nothing of an alleged mutiny. A few sailors promised to inquire about the mutiny and contact Milits when they returned to Stockholm [104]. One week later, Alex Milits received a phone call. A Russian voice asked if he were the one inquiring about the mutiny. The caller sounded very nervous and refused to give his name. He told Milits that he had just returned from Riga and had seen a naval vessel damaged by bombing. This damaged vessel, the caller said, had participated in the chase for the mutinous ship. When asked by Milits what sort of ship had tried to escape, the caller replied in Russian, "Storozhevoy." He then suddenly hung up [104].

Milits admits he misunderstood the size of the ship involved in the mutiny at this time. The Russian words "Storozhevoy korabl" referred to a small coastal escort ship. He therefore thought the mutiny had occurred aboard that type of ship rather than the much larger Krivak class ship named Storozhevoy. It was with this information that he published the first account in Expressen of a mutiny on a Soviet escort ship.

Four days later Milits was called by another seaman who had been read the article in the paper by a Swedish shopkeeper. The sailor told him he was in error. The mutiny took place on a destroyer. The Russian also told him to read a certain issue of Krasnaya Zvesda. He also hurriedly hung up stating that "someone was coming." The issue he was referring to was the December 24, 1974 issue that was cited earlier in this study. With the information provided in that article, Milits found that research became easier and through interviews with tourists, Lithuanian fishermen, and merchant sailors, he published, a much more accurate account in Expressen in May of 1976 [104].

Other newspapers in competition for the story and any information about the mutiny found information hard to obtain. In retrospect it is evident they often used less than reliable sources and produced wildly exaggerated accounts. The Daily Telegraph of London reported that the Storozhevoy actually reached Sweden, but was denied asylum by the Swedish Government. The report said sailors jumped overboard and were machine-gunned in the water by Soviet aircraft while the Political Officer and five co-conspirators committed suicide aboard [76]. The Latvian Information Bulletin quite understandably reported the crew was a majority of Latvian nationals and the mutiny was part of a larger nationalist uprising in Riga.

The Swedish Military High Command initially said nothing about what they knew concerning the mutiny but when reporters began their inquiries in February, they did very little to dispel the rumors. Reporters who questioned the High Command about the incident received only a very diplomatic response: “...the command staff confirms that during routine monitoring of radio traffic in this time frame activity that deviated from the norm was noted." [75:2] T.ie spokesman "absolutely" declined, however, to confirm that the Soviet radio traffic had pointed to a mutiny. "On the other hand, neither could he deny this supposition." [71] This author feels from the research, that the Swedes made a concerted effort to get the actual information distributed, off the record, to various, journalists. The Swedes' reluctance to make an official statement could be explained by their sensitive neutral position or the need to protect intelligence collection capabilities. The most important reason, however, was not made public until September of 1976 when a leftist Swedish fortnightly journal Folket i Bild-Kulturfront accused the former Swedish Defense Minister, Sven Anderson, on “paying a one million dollar bribe to U.S. Air Force General Rocky Triantafellu, head of Air Force Intelligence, over the period of 1970-1973 [104 ]. The Swedish military was forced to explain that the four $250,000 payments were not a bribe but a perfectly legitimate business transaction to purchase electronic equipment used to listen to Soviet Bloc military communication traffic. Sweden’s Baltic neighbors and some domestic public opinion were horrified over the disclosure of the classified deal with the Pentagon, since it was too naked a breach of Swedish neutrality [38]. Stig Synnergren, the Commander of the Swedish Armed Forces, confirmed at a press conference that the equipment had been used to monitor messages sent by Moscow to Soviet bombers pursuing a runaway Soviet frigate. He acknowledged that the money laundered through commercial banks, came from a secret Defense Ministry fund [88].

Captain Thomas Wheeler, USN, who was the Naval Attache with whom he had spoken were actually very glad that the Storozhevcy did not reach Sweden and that they were not faced with the question of granting asylum to the mutineers. The officials stated that they had always granted asylum on an individual basis to Soviet defectors but mutiny, a serious crime in any Navy, in the face of Soviet pressure was a potentially different matter. In light of Swedish reaction to the Soviet submarine which ran aground near the Karlskrona Naval Base in October 1981, it appears the Swedes have taken a tougher stand against Soviet pressure.

C. U.S. REACTIONS

The American reaction was even more muted than the Swedish one. Again, Captain Wheeler told of several State Department messages which instructed U.S. Embassy personnel to "keep the lid" on the incident [105], The explanation for this is probably found in the fact that the US. was still attempting to maintain some sort of detente with the Soviets and did not wish to embarrass them on the international scene.

A second possible explanation was that the U.S. needed to protect its own intelligence capabilities. This, however, is refuted in that U.S. intelligence personnel have said that "the incident was over before we knew what was happening" and "we had nothing focused to gather any information." So, it appears the U.S. Government, like the press, was at the mercy of the Swedes for accurate information.

Another possible explanation is that at the time of this incident the Ford/Kissinger Administration was locked in battle with Congress to appropriate funds to support the FNLA/UNITA factions in the Angolan Civil War. The Soviets and their Cuban proxies were heavily supporting the MPLA faction. The administration certainly would not have wanted to amplify or confirm an event which might show weakness in the Soviet military machine at a time when they are trying to get funds to oppose it.

The only semi-official U.S. Government statement at all was by Representative Larry McDonald (D., Georgia) who, on June 9, 1976 after being told the same exaggerated information cited earlier, offered a resolution condemning Sweden for their refusal to grant asylum to the crew of the Storozhevoy [27:12]. The U.S. Government historically has riot commented on instances such as this mutiny and with the lack of concrete data at the highest levels and the a foresighted reasons, the lack of comment here is understandable.

VII. POTENTIAL CAUSES

Until one of Stoiozhevoy's ex-crew members is allowed to speak, the world will probably never know the actual cause of the mutiny. There are, however, a number of potential factors which must have contributed to the reason for the few crew members to try such a desperate act.

The most significant possible explanation will not be covered in this study. The dissatisfaction in general with the Soviet government and life under its totalitarian rule has been written about in countless books. As an explanation for dissent, such dissatisfaction must be implicit in any work about the Soviet Union, In addition, a number of causes that will be cited pertain to problems in all of the Soviet society. This study focuses on those causes only as they relate to the Soviet Armed Forces or more specifically the Soviet Navy.

A. ANGOLAN CIVIL WAR

Until the U.S. Congress refused support for the opposition factions in the Angolan Civil War on December 9, 1975, the Soviets certainly feared that this West African conflict could spread into a superpower confrontation. Their Naval build-up in the area attests to this fact. The Soviets also cancelled all Navy leaves at this time. Finally, those conscripts who were due to muster out of the Navy in early autumn of 1975 were extended indefinitely. Normally the old ones would depart once they trained their replacement. (This would apply to one-sixth of the conscripts onboard the Storozhevoy, since they serve a 3-year tour of duty and are released only twice a year--in the Spring and Fall.) [53:38] One sailor on another ship was quoted as saying: "What do we have to do with the fact that some black apes in Africa want to cut each other's throats? We want to go home!" [104] Any military man in any country would agree that to hold any sailor past his obligated service, when a national emergency is not apparent, is grounds for potential dissent.

B. ETHNIC CONFLICT

A second potential cause is the nationalities issue. This factor has received considerable attention lately with the increase in Central Asian population in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Navy, however, takes only eight percent of the men conscripted annually and can thus be selective [93:60]. Along with the Strategic Rocket Forces, the Navy gets the cream-of-the-crop. It is estimated that Slavic nationalities comprise over 90 percent of the enlisted ranks and virtually all of the officer corps [98]. Ethnic friction is an admitted fact of Soviet military life in the army, but Soviet authorities admit that the Armed Forces are their best instrument of national integration to deal with the ethnic diversity [53:34].

It would seem that at first glance those who cited Latvian nationalism as a potential cause for the mutiny should be discounted. The Soviet policy of "extraterritoriality" means preventing any Baltic conscripts or other minorities from being stationed in their homeland [54:10]. In addition, since Baltic peoples are generally considered "less than reliable," they would probably not serve in the Navy at all but in construction battalions in Siberia [11:107]. Interviews conducted by this author indicate in fact that there are sailors of the Baltic nationalities serving in the Baltic fleet. One former sailor who served in Tallinn said that anyone with any connections or money can get his son to serve out his conscripted time close to home. He said this was especially common in Latvia and Estonia [106]. Russians historically have had a continental focus and have not been the greatest sailors, where the Baltic peoples, Latvians included, possess the skills from a very long fishing and seafaring tradition. In addition, the Baltic nationalities are highly educated and technically-oriented. These two factors make them ideal for Naval service and thus a nationalist cause for the mutiny does exist for those still chafing over Latvian incorporation in the USSR.

Some of the press reports said that disaffected Jews led the mutiny [73:4]. This is not likely due to the fact that Jews at this time could emigrate relatively easily. Why should they risk their lives to do it? The opposite effect may be more important. The relative ease with which Jews could emigrate could have added to the frustration that non- Jewish Russian sailors felt in not being able to do so, thus forcing them to more violent measures.

The Russian military is regarded by many Baltic peoples as an occupation force. Fights between Baltic citizens and Russian servicemen stationed in the Baltic states are often reported [106]. This kind of atmosphere cannot be conducive to good morale among Soviet sailors.

There are over 100 different nationalities in the Soviet Union. The Navy, as stated, takes only a few minorities but they do exist. Central Asian peoples are found in many assignments, but in small numbers and usually in lower ranks. Jews are more common in the medical and technical fields and serve in the fleet in both the officer and enlisted capacity. The Naval reserve in the Baltic area is comprised primarily of Baltic peoples, but the commanders are still Russian. Few minorities get advanced assignment and even fewer become officers [93:27]. One sailor interviewed said he never saw an officer of any other nationality other than Russian, Belorussian or Ukrainian [106].

The race-conscious Russians have been successful at their attempts to "colonize" the non-Russian nations. Russian migration throughout the country has ensured domination by the Russians in key leadership positions. This "Russification” has caused considerable resentment in many minorities, particularly Baltic people. Balts, thus are often thought to be security risks. On one occasion, the Estonians on the crew of a Kresta 1 class cruiser were removed prior to a cruise to the Mediterranean [107].

Ethnic frictions exist, but they are something that has to be dealt with in the multi-national Soviet society. These frictions tend to be less in the Navy than in the other services due to the closeness of shipboard life.

C. LIVING CONDITIONS

Morale problems associated with harsh living conditions can be particularly significant for naval personnel. The habitability of Soviet ships is substantially lower than that of corresponding Western vessels. Reports of poor conditions are substantiated by Western observers after visiting Soviet ships. Soviet ships are much more heavily armed than Western units of similar tonnage, and that has to be accomplished at the expense of the crew's comfort.

There is a great deal of difference between conditions on older ships and those recently built. Soviets have realized that living conditions, especially on the now more common longer voyages, have a great effect on morale. The greatest change is air-conditioning in the crew's quarters since more and more cruises are going to tropical climates.

The overall impression one receives when visiting a Soviet ship is that it is far from luxurious, cramped, drab but clean. On the older "Kotlin" class the berthing spaces are dimly lit and crowded. (Although one source said "crowded makes for better cooperation"). [107] Bunks are three-tiered with a 2 foot by 2 foot non-lockable box for each sailor. The spaces are not air-conditioned although space air-conditioners are carried on voyages to the tropical climates [107]. There are no water fountains in the living areas. Drinking water is available from a portable metal barrel with a community drinking cup [106]. On older ships, food is carried from the central galley and consumed in berthing spaces [35:212].

In contrast the Smolnyy, a Soviet midshipman training ship that was put into service in 1976, is centrally air- conditioned. It has a comfortably furnished officer's mess, and three dining rooms for the enlisted. The Smolnyy, in addition, has a "Lenin room" in which political instruction is given, which accommodates forty men. The ship also has facilities for movie projection and a 6,000-book library [52].

Visitors aboard the helicopter carrier Moskva described their impressions as: limited space, spartan. living conditions, rudimentary equipment and one unusual condition-- the presence of Russian girls (nurses) in their white uniforms. It seems nurses are not uncommon on the largest ships. The all-pervasive smell aboard Moskva was described as "a mixture of cabbage soup, bacon fat. and that black, slightly rancid typically Russian tobacco." [2]

The Northern Fleet sailor who served on the Kresta I class ship "Admiral Drozd" described major morale problems in association with Soviet Naval inability to get mail to ships on long cruises distant to the Soviet Union [107]. This was in 1970. It is unknown if this situation is any better today.

The Navy exists ashore as well as afloat and accommodations on land appear to be worse than those at sea, particularly in such inhospitable areas such as Polyarnyy in the Arctic, Vladivostok or Petroparlovsk. Victor Belenko, at a MIG-25 base in the maritime provinces of the Russian Far East, lived in a two room apartment just prior to his defection. With him were his wife, a flight engineer, the engineer's wife and their two children. They considered themselves lucky. Other apartments were packed with three and four families [5:97].

The Soviets, it seems, are aware of these problems and write about them, but according to Belenko and others, do not give it the priority it deserves. In Krasnaya Zvesda in 1974, Rear Admiral Sidorchuk (Chief of the Fleet Rear Services) discussed the housing situation for Navy men in the Pacific Fleet in fairly frank terms. He stated:

...the Party and the government are showing consistent concern with regard to improving the housing and living conditions for service families... In the Pacific Fleet in the last three years alone, thousands of families have received new living quarters. There is a problem of maintenance, however. In isolated far-off garrisons there is often a lack of trained maintenance specialists.... In some areas house maintenance committees exist solely on paper and actually do nothing. This had resulted in problems which can affect the serviceman in the performance of his regular duties [72].

Housing for servicemen in other areas of the Soviet Union is better but not without problems. Members of the military, particularly officers, are given priority on the list to receive new housing in urban areas where a shortage exists. Victor Belenko, as a newly reported aviation instructor in the Western Soviet Union, related his excitement over getting a new apartment in a building only one month old:

To be promised an apartment was one thing, but to be given an apartment as promised, quite another.

Eagerly and expectantly, I unlocked the door and smelled dampness. The floor, built with green lumber, already was warped and wavy. Plaster was peeling off the walls. The windowpane in the kitchen, was broken and no water poured from the faucet. The bath tub leaked; the toilet did not flush. None of the electrical outlets worked... Another lieutenant and I confronted the first party representative we could find, a young political officer in the same building. Ha was cynical yet truthful. The building had not been inspected as they had been told. The military builders sold substantial quantities of alotted materials on the black market, then bribed the chair - man of the acceptance commission and took the whole commission to dinner. There the acceptance papers were drunkenly signed without any commission member ever having been inside the building [5:75].

The Krivak class, of which the Storozhevoy is a member, possesses the same shipboard habitability problems as other Soviet combatants. It is cramped and spartan. Morale problems due to the poor habitability would therefore be understandable. Those Storozhevoy sailors living ashore in barracks or with their families were not faced with the grim conditions that existed in the Soviet far east, Riga is a large and relatively modern Soviet city. Housing is still scarce, however, and newer housing has quality problems due to corruption in the construction industry. Living conditions should be considered as a probable cause for the mutiny.

D. FOOD

In the Soviet Union where military power is so extremely important you might expect the consumers to suffer somewhat so that the military soldier and sailor might eat very well.

It seems that this is not the case. Food certainly could be a cause of low morale, but how bad can the food be? Sailors in every navy complain about the food. In the Soviet Union food consumption has doubled from 1950-1974 [50:74], but it appears there are still a large number of problems in getting adequate food to the sailors.

The Soviets, in their regulations, appear to be very concerned that the troops in the military are well fed. Rations are provided free of charge to all soldiers, sailors, cadets and reserves when on active duty. Soviet authorities often boast about their ability to provide the troops with adequate rations. It is also official policy to see that elite forces receive better food than regular line forces [15:51].

Officers, if they serve in the elite Strategic Rocket Forces, receive free rations. Pilots receive four meals a day, also free. Sailors and flying personnel receive 4,692 calories per day where soldiers receive only 3,547 [47:81]. Officers who serve in certain isolated regions of the USSR or abroad either get free rations or pay only half the cost. Strangely enough, officers who serve above the altitude of 3,500 meters get free rations as well.

Servicemen abroad get a tobacco ration. Nonsmokers may opt for 700 grams of sugar instead. Within the USSR, soldiers, sailors and cadets get eighty kopeks a month for tobacco [47:81].

The Soviet regulations do not specify anything concerning the quality of the food. An average daily menu paints a somewhat different picture. Soldiers are fed breakfast from 0730 to 0800, The morning meal generally consists of a bowl of kasha (a barley or oat mush cooked with flour) with 150 grams of bread, 10 grams of butter, 20 grams of sugar and a mug of tea [5:97].

Lunch is the main meal. Soldiers and sailors are given forty minutes to eat followed by thirty minutes rest. Lunch consists of a thin potato or cabbage soup, sometimes thickened with buckwheat groats. If they get any meat at all during the day it will be included in this soup; either a piece of cod, herring or a hunk of pork fatback. On special occasions, a mug of kissel (a kind of starchy gelatin) will be added along with more bread [40:46].

In the thirty minutes alotted for supper, servicemen are served many times the same meal of kasha and bread they had for breakfast. If they get any fresh vegetables it will be at this meal in the form of cooked cabbage or mashed potatoes [106]. Finally, they receive more bread. A Soviet serviceman consumes an average of one and a half pounds of bread per day [40:46]. Primarily due to this excess starch, he manages to gain six to eight pounds during his conscripted service. In the West, the average weight gain for young men in the age period of 18-20 years is almost double that.

Servicemen can try to supplement their diet at their unit's "bufet" (snack bar), but a conscript's salary of 3-S rubles per month (approximately four dollars), cannot really buy too many of the cookies and candies sold there [90:9]. Thereby, only those sailors who receive money from home and can buy other food on the civilian economy are able to eat any better.

It appears in terms of calorie intake, the diet is suf-ficient. It is, however, dull and without certain essential vitamins. A former sailor interviewed by this author stated, "It filled you up but made you feel sluggish all day." [106]

The conditions under which servicemen are forced to eat do not add to the enjoyment of their food. Victor Belenko described conditions at an air base in the Soviet Far East:

Between 180 and 200 men were jammed into barracks marginally adequate for 40. Comparable congestion in the mess hall made cleanliness impossible, and the place smelled like a garbage pit. While one section of 40 men ate, another 40 stood behind them waiting to take their places and plates. If they chose, they could wait in line to dip the used plate in a pan of cold water containing no soap. Usually they elected simply to brush the plate off with their hands and sit down due to the short time for eating [5:99].

In the Navy, as mentioned earlier, there is no general crew's mess aboard the older Soviet ships. The food prepared in the galley is carried to the crew's berthing spaces to be consumed. This is not only cramped and unsanitary, but dangerous since fires due to heating elements have been reported [35:212]. When the heat below deck becomes intolerable sailors eat on deck on oilcloths with no tables or chairs [97:85].

Former members of both the Army and Navy agreed that food in the Navy was better in both quantity and quality. In addition, Navy personnel stated despite how bad their food was, they were fed better than the civilians in the surrounding communities. Naval personnel received some meat almost every day. In addition, they were the only ones to respond that they received coffee.

The army infantry and construction troops receive the worst rations of all. A Soviet army unit subsisted on kasha and codfish alone for thirty days without any variety [14:32]. Complaints about food often follows ethnic lines. The only meat one army unit ever received was pork, something Muslim Central Asians refused to eat [14:39].

There is some evidence that Soviet soldiers in the field often suffer from various illnesses related to vitamin de-ficiencies. One soldier who was stationed with an air defense battery near Murmansk reported that troops in his unit often developed sores and skin ulcers, sometimes accompanied by eye infections and night blindness [15:52]. These and other illnesses, such as severe acne, rapid tooth decay and chronic sore throats, all of which plague Soviet soldiers, are traceable in many instances to vitamin deficiencies. In some areas troops were given vitamin pills to supplement their diet, but one soldier testified that they were not taken in his unit under the suspicion that they contained saltpeter! [15:52]

Fresh fruit is unheard of in the Soviet Armed Forces. A sailor who served on a cruiser out of Murmansk never saw fresh fruit in his three year? of conscripted service [107].

Soldiers' feelings about food are very strong. A former private who, during his service in the early seventies was quartered for some time near a military installation in an area where servicemen from other Warsaw Pact countries were training, said in reference to the Warsaw Pact allies:

They had an excellent mess. Soldiers from our battalion were twice sent on kitchen duty to their messes. They came back bringing pancakes! They brought sour cream! My friends were among them, so they brought some to me. It seemed like a miracle. We remembered it to the end of our service [90:9].

Dissatisfaction of soldiers with food has led to open protest, usually refusal to eat. A former paratrooper told how, after a year of particularly bad harvest, each soldier's ration of butter, bread and sugar was reduced. The soldiers after a brief organizational meeting, refused to eat. Half an hour later the division political officer appeared and ordered rations increased to their old levels. They were never reduced again, and no one was punished for his disobedience [90:9].

In interviews with former soldiers, Dr. Robert Bathurst reported that a majority feel that their food situation is worsened by dishonesty on the part of the NCO’s responsible for the galley. In addition, senior conscripts often extort food from junior conscripts as part of a general policy of hazing (discussed at length in the next section) which is overlooked by senior enlisted personnel and officers. The fact that everyone steals food, particularly meat, is widely recognized and accepted.

It must be stated that the Soviet soldier is quite accurate when he complains about the quality of food available to him. Even with the low standards of Soviet society, the majority of soldiers in the regular units believe that food is worse than that found in civilian life. Military rations are monotonous, poorly prepared and inadequate in terms of vitamin content. Although the number of calories appears sufficient due to the high starch content, it still does not appear to be a diet adequate enough to sustain a young mun through the rigorous Soviet military day.

When one looks, however, at how this impacts the combat ability of Soviet soldiers and sailors one must be careful to look at it with a Russian mindset. Certainly, if volunteer American soldiers were fed in the same fashion as conscripted Soviet troops, an open revolt would occur. Many Russian peasants have eaten boring, untasty food all their lives and their short stay in the military is little different.

It is the style of every soldier in the world to complain about his food, but the Soviet Union might be the place where the serviceman has a real reason to do so. It is said that "an army moves on its stomach," if so, the Soviet military is. not going very far. Today's relatively moro urban, will- educated Soviet draftee is apparently less willing to accept the material hardships of military life. Moreover, none of the current conscripts have had first-hand experience of the trying years of World War II, an experience which is viewed by the Soviet leadership as an important source of Soviet patriotism.

The author has no testimony concerning the quality or quantity of food onboard the Storozhevoy. One can only infer that it was very similar to that in the rest of the Soviet navy. Poor food can therefore be cited as one potential cause of the mutiny.

E. HAZING

One of the characteristics of Russian society is its harsh stratification. This stratification is carried over into the military service. Russians subordinate themselves, at least on the surface, to those above them in the hierarchy. They also tend to distrust and abuse those below them on that same ladder. In the Soviet military this is translated into "hazing.” Second and third-year conscripts have long enjoyed seniority over younger draftees, claiming special privileges with the unit and channeling the undesirable duties to the new men. Emigre sources indicate that moderate hazing is accepted by the conscripts and tolerated by officers and petty officers because it provides a convenient way of maintaining unit control. Excessive hazing, however, can lead to low morale of the younger draftees and less solidarity of the unit as a whole.

The soldiers and sailors are generally divided into two groups: the "young ones" (Molodye) and the "old men" (Stariki) [90:4]. The former are the conscripts in their first year of service and the latter are those in their second of final year of service.

Before the 1967 Law of Universal Military Service reduced the length of time served in all Soviet land forces from three to two years, there had been an intermediate group in their second year of military service. This group of course is still present in the Navy where sailors have the three-year conscripted obligation.

The "Stariki" rate a number of privileges at the expense of the "Salaga" (a derisive nickname for first-year sailors) [107]. When new conscripts arrive at their unit, one of the first orders of business is the uniform exchange. The "old men" exchange their worn uniforms for the new ones of the young first-year conscripts. The "Stariki" generally want to return home after demobilization in brand new uniforms [106]. A sailor who served on the minesweepers in the Baltic Fleet sold the new uniform to Central Asian army troops who found it more prestigious to go home in a navy uniform [106], All of the heavy work and menial chores such as cleaning and kitchen work are done by the "Molodye." A source in a Riga signal battalion had to shine boots for the second-year men (He was a shore-based sailor and thus only served two years). First-year sailors in his unit had to give up parts of their ration of sugar and butter to the "Stariki." The "old men" also demand a share of each food parcel or money gift received from home by the "young ones." [110]

This system does not appear to meet with a great deal of resistance. The conscripts are probably away from home for the first time at age eighteen and giving one "old man" what he v/ants without any fuss seems to provide the new conscript with protection from the otner "old men." ’Another explanation for the passive acceptance of this hazing is that in the two or three years of arduous military life, most of the conscripts become considerably stronger, particularly in the army. The threat of physical harm is often used as inducement for compliance. A recent study emphasized that attempts were being made to reduce physical violence used by the "old men” against the new recruits [90:5].

An émigré now in West Germany corresponded that when he became a "Stariki," he and a few of his comrades were deter-mined to treat the first-year men better and with dignity.

This worked satisfactorily for a few weeks until a senior enlisted man discovered that the source and his comrades were being too easy on the "young ones." The lenient "old men" were ordered to dump thirty buckets of water in their barracks and clean it up with small rags. While these "Stariki" were cleaning up the mess the "Molodye" were given free time. After this incident, the senior NCO had a meeting with the "Stariki" and told them to put more pressure on the first- year sailors or this incident would repeat itself [110].

Fist fights broke out often between junior and senior conscripts, particularly over the uniform exchange. Most of these fights go unreported or are overlooked by senior enlisted personnel and officers in ill the services. This episode told by a former private in the Air Defense forces illustrates this:

...during dinner an "old man" received a slightly yellowish enameled cup (Usually the "Stariki" received only the new white cups). The "old man" without looking back threw the cup with all his strength into the open kitchen door and hit a young Kirghiz soldier who was on kitchen duty directly on the forehead. The "young one" was in great pain, but he did not dare to complain or seek revenge. The onlookers took the whole episode are no more than part of the army life. They all said, "That's the way things are." [30:5]

It is apparent that the officers not only know about the privileged position of the "old men" but readily encourage it. An army NCO stated that the officers for whom he worked did not find it unreasonable when a "Stariki" complained about. too much work to do. Officers said that the "old men" deserve some privileges because they already know their jobs and besides everybody gets to be an "old mar." eventually [90:6].

The émigré, who served on a cruiser out of Murmansk said this conflict between junior and senior conscripts was the worst single cause of problems aboard his ship. He said authorities were attempting to deal with the ethnic problem, but the disruption caused by hazing was being overlooked [107]. Hazing is a navywide Soviet problem and was a morale problem on the Sorozhevoy.

F. ALCOHOLISM

Prince Vladimir of Kiev is said to have made Russia Christian rather than Moslem because, as he put it, "It is impossible to be happy in Russia without strong drink." Alcoholism is a national malady which permeates the military forces. Alcohol consumption among Soviet citizens accounts for over a third of all consumer spending in food stores [13;44], The situation in the armed forces shows that servicemen are not exempt from the disease afflicting society as a whole.